An Unsophisticated Translation

Review

This nation has an amazing poetic pedigree and an outstanding tradition of literary translation. Its singular downside, though, is its paucity in the outside world. The cause of this regrettable shortage is the abundance of Georgian poesy versus the scarcity of its translators, as well the height of the Georgian poetic thought versus the overall translating inaptitude. To put it in a more mundane frame of thinking, if elevated poetry were a salable commodity, Georgia would definitely be the richest nation on the planet. The potent poetic interpretation of philosophic reasoning in Georgia is connected with the creative genius of Shota Rustaveli: the preeminent poet of the Georgian Golden Age who bestowed on civilization the unparalleled epic poem ‘Knight in the Panther Skin’ which goes beyond epochal limits or national boundaries. Hence, the worldwide interest in its translation is commonplace. In the last hundred years, there have been numerous attempts to translate the Rustaveli poetic opus into various languages. English is certainly one of the most appreciated recipients of this particular Georgian mythical colossus. The efforts of translation continue to occur, and the proudly grateful Georgians watch the process assiduously.

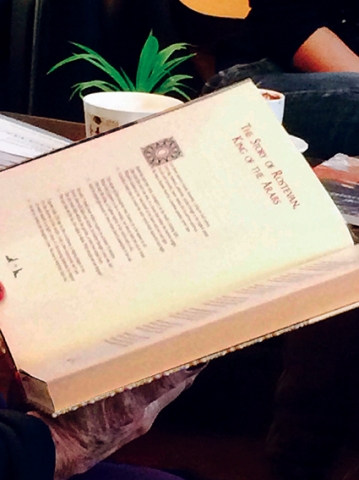

A few years ago, I came across, and I am still reading into it laboriously, a new translation of the poem by Lyn Coffin, accompanied by a brief Foreword by professor of Russian and Eurasian Studies Stephen Jones, who says that the translator is faithful to both meter and size, yet does not lose the beauty of Rustaveli’s poetry. I am not sure how well versed the author of this presumably fortuitous praise is in the Georgian language, but the translator has certainly gone astray from the exceptional beauty and powerful eloquence of Shota Rustaveli. Jones continues that Coffin has preserved the splendor of Rustaveli’s great adventure story. We all know that the story is great, but preservation of the Rustavelian splendor is a sheer exaggeration, although the translation is ‘readable’ enough.

The problem is that readability is not enough a credit for qualifying a translator as ‘a meticulous wordsmith,’ as Mr. Jones has put it. A translator of a poet as gigantic as Rustaveli cannot be considered ‘a passionate artist’ only because he or she made another modest attempt to handle the great Rustaveli. A job of this significance is undoable unless the translator of the piece of this magnitude is fluent in the Georgian language and has a feeling for the intricacies of this tongue right to the bones.

Consequently, Coffin’s translation of ‘The Knight in the Panther Skin’ felt to me like a simplistic attempt to render it in English, a far cry from the way the original sounds and feels. To cut a long story short, the present new translation is not a good enough recipient of the source text for the simple reason that it sounds less sophisticated and euphonic than the original. And it is very important to note that this straightforward opinion could be translated into a critical word only by a reader whose knowledge of the two languages is adequately matched and whose expertise of translation is sufficient for the judgment of this level.

As a result, the Georgian culture and intellectual veneer is being deprived of its luster and value in the eyes of the global reader, which may perceive us through the primitive prism forged by the Coffin translation.

The pearl of the acknowledgment at the end of the book is an excerpt from the Afterword: “As is commonly said, in the translation of prose, the translator is the servant and slave of the original author, whereas in the translation of poetry s/he is a rival. The pleasure of reading this new English text testifies to how worthily and courageously the translator rivaled her great 12th century forebear.” In the first place, the issue of servitude and slavery to the original is a matter of sharp controversy, and secondly, the rivalry of Coffin with Rustaveli sounds a little ludicrous, to say the least. Why do we have to downgrade the famous Georgian literary might that much?!

The last nail is driven by the concluding paragraph of the publisher’s note, where Umberto Eco himself is quoted: “When I visited Georgia, they told me that their national poem ‘The Knight in the Panther Skin’ was a great masterpiece. I agree, but he’s hardly caused the same stir as Shakespeare.” Understandable! Eco probably read Shakespeare in the original. He could only have made a guess about the stirring power of Rustaveli’s poem. The publisher’s optimistic conclusive note is scarcely any encouragement for us Georgians. Just listen to this: “Now Mr. Eco and the rest of the world have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to appreciate the true magnificence of Rustaveli’s work, and hopefully, some stir will be caused.” Hardly!

By Nugzar B. Ruhadze