EXCLUSIVE! Redjeb Jordania on Georgia, Past & Present

Exclusive Interview

As Georgia prepares to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Democratic Republic of Georgia (DRG) declaring independence on May 26, 1918, everyone’s attention is focused on Noe Jordania, the man who led his country for three short, but very productive, years, until February 25, 1921, when Soviet troops annexed the fledgling First Republic. Jordania’s government left the country and lived in exile in France, working tirelessly towards restoring Georgia as an independent state. The son of the First President and Head of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, Redjeb Jordania, is visiting Tbilisi this week from New York, where he lives with his extended family, to celebrate this day in the capital of Georgia, Tbilisi.

We meet in the lobby of his hotel. The 96-year-old man walking towards me looks remarkably fresh after the long transatlantic flight the day before.

He’s been in touch with Georgia, despite not having visited it since 2011. The first time he ever visited Georgia was to address the democratically elected statesmen in 1990, and he wrote a passionate speech to all Georgians on May 26, 2015.

“After that first visit in 1990, I have been to Georgia many times, for various reasons,” Redjeb tells us. “It was always a part of my life: my daughter and grandson lived here. Myself, I was looking for ways to help a restored Georgian state. It’s been several years since my last trip, though: in 2011, I suffered multiple broken bones as a result of an accident, and for a long time was in no shape to travel. Then, Nicole [his daughter] and her family moved to NYC, and there were fewer reasons for me to make this long journey. But my heart was always with Georgia,” he confesses.

He has published books and articles, participated in conferences – just a couple of weeks ago, in Washington, and this April, “The Forgotten Father of Georgia’s Modern State” was published, with a preface from Molly Corso, an article by Prof. Stephen Jones, and an excerpted memoir from Redjeb’s book “All My Georgias.” In it – and among many other memoirs, Noe Jordania is described as a very imposing figure, larger than life; an intellectual transcending his time; authoritative, but not authoritarian. One gets a sense that one of the biggest things that defined our first president, was charisma.

“Well, people said that he would seem taller when he was in Georgia, and I saw that when the important visitors came to our place in France, he would change,” Redjeb says of his father. “But my personal impression was totally subjective – as a child, I regarded him just as a father; tenderly and with love that doesn’t need analysis.”

ON WOMEN IN POLITICS

All his life Redjeb Jordania was surrounded by strong women- all very independent and determined, starting with his grandmother. His mother Ina, who was the first woman of any nationality to be enrolled in Sorbonne Law school, and her sister Felichka, who was a Professor of Math in Tbilisi, were not just independent, but exquisitely educated. So, the tradition of strong professional women in Georgia is not news to Redjeb. We asked him how he viewed the chances of their being a female president in the upcoming elections.

“Georgia has a way of surprising,” he replies. “It’s a field of personality politics. So, who do you have here? Who can be the contenders? I don’t know the personalities, I don’t know the situation in Georgia well enough to even attempt to answer. But let me bring in the angle that is not discussed much in modern Georgia. Every time the state is under a strong influence from the religious circles or authorities, there’s never a woman in a top-power position. In order for this to happen, as a pre-requisite, the religion has to loosen its grip on people’s lives. Virtually everywhere, organized religion is supporting male domination and doesn’t let women get ahead.”

The conversation turns to the Constitution of 1921 and the role of women who, for the first time, were given the right to vote.

“Georgia was one of the first states that allowed women to vote from 1918,” Redjeb confirms. “Norway had universal voting rights from 1913, Sweden, and several states in the USA (until the 19th Amendment in 1920 took it to the federal level). Another very interesting and proud moment for the DRG was that the first time in the world that a Muslim woman was democratically elected to the assembly, was in Georgia.”

National Council meeting, May 26, 1918. Museum.Ge

ON MINORITIES

That brings us to yet another chapter in the 1921 Constitution: protecting minority rights. Both the concept and the wording are decades ahead of even well-developed countries, for example: ‘It is forbidden to bring any obstacle to the free social development, economic and cultural, of the ethnical minorities of Georgia, especially to the teaching in their mother language and the interior management of their own culture.’

“Yes, the whole chapter on ethnic minorities was very progressive; no restrictions of any rights, civil or political,” Redjeb says. “But I want to tell you something else: I don’t like the current Georgian flag. I like the old one [points to his lapel pin]. This is my flag- I was born and raised with it. In 2004, when Saakashvili changed the national flag, I thought, what is it that I don’t like about it? It’s a wonderful banner, very joyous – so what’s wrong? And I realized, it’s because Misha’s flag has all these crosses, and it carries a subliminal message: if you are not a believing Christian, you are not a Georgian: this is not your flag. If you are a Jew or a Muslim, or anybody else, you cannot be a Georgian, and it’s priming people’s mind to be less tolerant to non-Christians.”

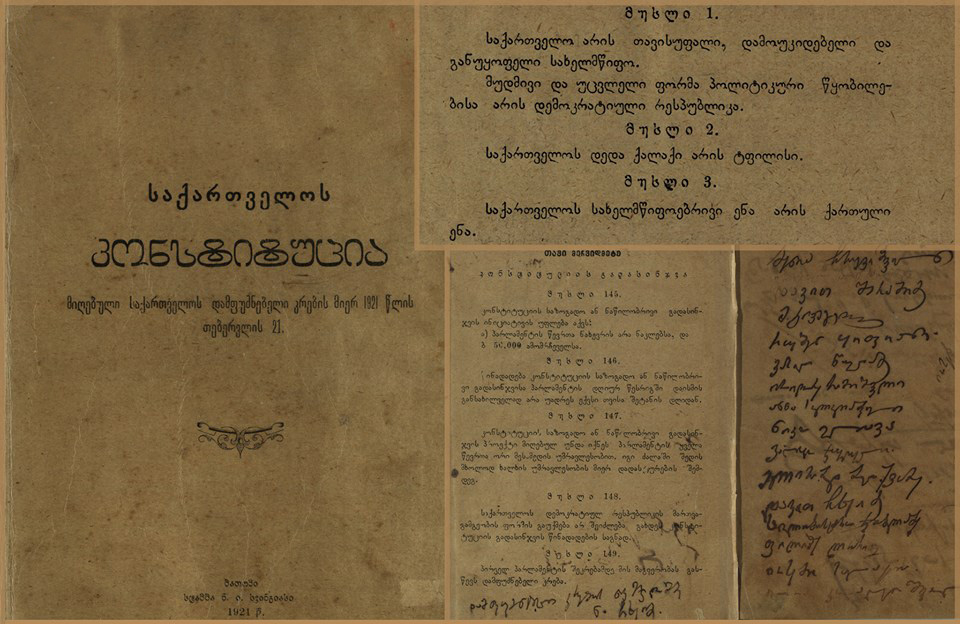

Fragments of the Constitution of Georgia adopted by the Constituent Assembly of Georgia on 21st February 1921

ON THE CHURCH

The DRG Constitution had a chapter dedicated to the separation of the Church and State, putting all confessions in an equal position before the law. But after the collapse of the Soviet rule, the Church took the leading position in Georgia, and every government since seems to be very dependent on their support. We wondered if Redjeb thought that Georgia had perhaps regressed from the principles of the 1921 Constitution.

“You noticed that the same thing is happening in Russia? Despite claims that Georgians have turned their back on the ways of Russia, they are doing the exact same thing,” he tells us. “The Church is very strong both in Russia and in Georgia. This is understandable as a reaction against the years when it was forbidden under Soviet rule. In Article 144, it states, ‘It is forbidden to make any levies on the resources of the state or the bodies of self-government for the needs of any religious order.’ In 1918, the Church as an organization owned significant properties in Georgia, and Jordania’s government took that land and distributed it among peasants.”

ON FINANCES

His father, when he was in exile, had very limited sources of income, so the financial situation of his family was quite difficult. Despite that, Noe Jordania was very discriminating about who he would accept money from. In many developed countries, there are debates about campaign financing. We asked Redjeb what his thoughts were of the money in politics and why it was imperative for a man like his father to keep integrity, and why it isn’t commonly seen in today’s politicians.

“It seems to me that back in the day, money was not that important,” he replies. “Politicians didn’t have to pay for TV time, or media, or take advertising. The idea of money wasn’t essential to politicians in 1918: discussions were centered around platforms.”

Noe Jordania came from a modest background, and supporting a large family, and the activities of the exiled government, came first.

“There were not too many options: writing articles, support from the party members. When we were living in exile in France, our means were very restricted,” Redjeb remembers. “As I explained in my book, there were regular payments from the Polish government for repatriation of a large number of Polish soldiers stranded on the Turkish front post-WWI, which Georgia took upon itself. Those funds financed the activities of the Georgian Government in Exile and provided modest pensions to its leaders, all the way till 1939, when Poland was annexed in WW2.”

Noe Jordania (1868 - 1953)

ON PERSONALITY POLITICS & CULT

In Georgia, there’s more personality politics than platform politics. Redjeb’s father seems to have had both, and was probably the last president, the last political leader, that Georgia has had who had both the personality and a political platform that he stuck to.

“If the personality doesn’t have a solid platform, it doesn’t work for long,” Noe’s son says. “In the First Republic, my father, and everyone around him, had a platform of Social Democrats, which sometimes scared people of the 1990s. But Georgians in 1918 didn’t have the view of what they knew in 1990, the failure of the USSR that called itself a socialist country. So, to judge 1918 from todays’ standpoint is wrong; at that time socialism was on the rise everywhere. The 20th century was a triumph of socialism in terms of instilling socialist institutions: social security, insurance – the types of institutions that didn’t exist a century earlier. Progressive countries like France had the systems protecting its citizens and even Americans, who hate the word ‘socialism:’ they had socialist institutions there that they wouldn’t give up, like social security.”

The First Democratic Republic of Georgia platform was very progressive, some even called it idealistic, and it only had very few months to test itself out. We wondered if, hypothetically, the First Republic had not lasted three years, but 13, where Redjeb thought Georgia would be positioned among the countries that take social issues more seriously than others, like Scandinavian states.

“I’m glad you mentioned Scandinavian countries. There’s a good example for Georgia to consider: small countries, very prosperous, not particularly rich in terms of natural resources. Except for Norway, but even then, 30 years ago, Norwegians didn’t have them, and were still doing very well. Another similar state is The Netherlands. All of these states boast excellent social institutions, so, yes, Georgia, could have been among them, if not for the Soviets.”

Georgians are prone to the cult of personality. Even in post-Soviet years there was Gamsakhurdia, then Saakashvili.

“The reason is possibly that the Tsarist Empire didn’t leave room for personal development. It lasted for many years, and continued with the Soviet rule, which didn’t help, either,” he notes. “It is interesting that of all the Georgians who have emigrated to the USA, 90% vote Republican- they still want the strong figure, the strong hand. But going back to Gamsakhurdia, compared to the First Republic, which had a difficult local situation, collapse of the empire, civil war in Russia, WWI, he inherited an ideal situation: a peaceful environment, support of all big powers like the US. And he managed to fail, brought the country to civil war, was ousted out of office in few months, lost Abkhazia. Also, I want to mention the contrast, the difference in people in the time of the Democratic Republic and Jordania Government, and the 1990s, Gamsakhurdia’s time. In 1918, people supporting my father. Many of them had been abroad, they studied and learned from the institutions in progressive countries. In contrast, the Gamsakhurdia electorate was a product of the Soviet rule, of the “iron curtain:” they had never been abroad, they were afraid of progress, and pushed ultra-nationalism as their platform. Gamsakhurdia was very adamant in calling himself the First President of Georgia, as if he was competing with my father; saw him as a rival, not as a statesman whose institutions restored an independent state. And another President, Saakashvili: he replaced the flag of the DRG with his own banner, it was a part of his cult, instilling his symbol.”

The Soviet Russian 11th Red Army holds military parade in Tbilisi, February 25, 1921 / Kober

ON THE SOVIET EFFECT

“The DRG, albeit short-lived, managed to create a sense of nation, to build institutions,” Redjeb says. “For centuries, Georgia had not been a united independent state. My father told me that in the 1900s, people had the sense of belonging to a very limited, local community- within the village, maybe, or province. There was no ‘nation.’ And that’s what the First Republic managed to change in three short years. The Soviets inherited this and kept the institutions created in 1918.

“This fit into their desire to erase the memories of the 1918 Republic, and yet feed the historic pride that Georgians carry within themselves,” Redjeb continues. “This substitution of a narrative started at the end of 1960s-70s, that’s where the nostalgia in Georgia became clear (after the clashes tied to the use of Georgian as a state language, the Soviet system had to back down and bury the idea of instilling Russian instead). For the USSR Bolsheviks, the biggest enemy was not the capitalism, but the social democrats of the DRG, because their appeal was to the same base.”

As the interview draws to an end, we agree to meet on May 25, to go to the museum offering a lecture on an original coat of arms from 1918. Redjeb is intrigued: he wants to hear the story behind it, and this youthful curiosity in a 96-year-old is unmistakably sincere. The 1918 coat of arms that he used for the cover of his book “All My Georgias: Paris-New York -Tbilisi” (2011), he likes more than the current one. More optimistic, he says, and less aggressive. Indeed, on the current coat of arms, St. George is slaying a dragon; on the old, he’s portrayed on horseback but just holding a spear. The background is simplistically elegant, without being overburdened by decorative elements. This is the way of Noe Jordania’s son: reflection instead of hasty judgement, optimism with a healthy dose of reality, simplicity of wisdom over convoluted innovation. As we celebrate 100 years of independence proclaimed by the First Republic, these are the qualities that Georgia, restored to independence, could certainly use.

By Kyra Devdariani

Main photo: Redjeb Jordania by Irakli Dolidze/GT