Bringing Georgia’s Realities in Line with its Euro-Atlantic Dreams

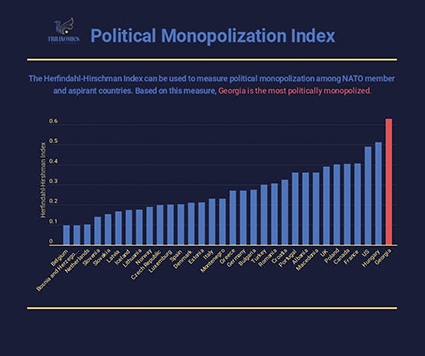

To be able to join the West’s military and political structures, Georgia has to upgrade itself in line with its Euro-Atlantic aspirations: educate its population, develop the economy, and, last but not least, address deficiencies in democratic governance, as reflected in its position on the Political Monopolization Index.

Georgia’s foreign policy drift away from Russia and towards the West started almost immediately after independence, when it joined the North Atlantic Cooperation Council in 1992. The following year, Russia intervened on Eduard Shevardnadze’s behalf in the civil war engulfing Georgia by stopping the advancement of Gamsakhurdia’s forces in Western Georgia. Yet, Georgia’s relations with its northern neighbor quickly soured over Russia’s accusations that Georgia sheltered Chechen rebels, and its own support for Abkhaz and South Ossetian separatists.

GEORGIA ‘GOING WEST’

Shevardnadze’s ‘bidirectional’ foreign policy sought to distance Georgia from Russia’s suffocating embrace, and bring it into the orbit of the US and its Western allies. With Georgia acquiring a new significance as a potential energy transit corridor, Shevardnadze was warmly welcomed by the Clinton administration. In July 1995, Georgia and the US signed a Bilateral Investment Treaty, paving the way for the construction of oil and gas pipelines across Georgia’s territories.

With Russian military bases still present on its territory, Georgia was brave enough to declare its NATO aspirations at the 2002 Prague Summit. Two years later, following the 2003 Rose Revolution, Georgia became the first country to acquire an Individual Partnership Action Plan (IPAP). Another breakthrough moment seemed to have come in April 2008, when the Bucharest Summit resolved that “Georgia and Ukraine will become members of NATO”.

The immediate next step was supposed to be a Membership Action Plan (MAP). What followed, instead, was the Russo-Georgian war of August 2008, giving at least some NATO members second thoughts as to the urgency of letting Georgia into the Alliance. More than ten years have passed since the Bucharest Summit, but Georgia is yet to receive the MAP. 2018 Brussels Summit resulted in nothing but the usual expression of satisfaction with Georgia’s military contribution to the Alliance and its progress in developing its economic and democratic institutions.

STUCK IN LOVE

Successive Georgian governments have been drawn towards NATO as a possible antidote to Russian occupation of the breakaway regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, its unilateral decision to recognize their independence in 2014-15, and the creeping borderization process that ensued. At the same time, popular support within Georgia for joining NATO, according to NDI opinion polls, is quite volatile. Moreover, when asked about the benefits of joining the Alliance, many Georgian citizens see it as a way out of social misery, rather than a means of addressing the country’s security challenges or strengthening its democratic governance.

Thus, we observe a peculiar dualism: Georgia is politically determined to join NATO, but this aspiration is not fully reflected in the individual perceptions of Georgian people. A similar ambivalence appears to be shared by Georgia’s Western allies. On the one hand, Georgia may have “all the practical tools to become a NATO member”, as recently stated by Secretary General Stoltenberg. On the other hand, however, the Alliance does not speak in a single voice when it comes to further expansion. Some NATO members (e.g. Germany and France) hesitate to grant Georgia the MAP, as this would imply an open confrontation with Russia.

With all their love for each other, Georgia-NATO relations appear to be stuck.

THERE IS A WAY OUT!

One way forward, suggested by Coffey (2018), is to invite Georgia to joint NATO by temporarily excluding the Russian-occupied territories from Article 5 protection. However, the suggestion that Georgia should decide whether it wants to become a member of NATO or give up on its territorial integrity – as implied by Coffey – is a false dichotomy in Georgia’s political realities.

Instead, Georgian policymakers should understand that integration into Euro-Atlantic institutions will not be possible without restoring the country’s territorial integrity. And, since only an enlightened, democratic and prosperous Georgia can hope to re-integrate the territories and people it lost in the chaos of the 1990s, domestic policy issues – rather than demands for immediate admission into NATO – should be at the center of Georgia’s policy agenda. In other words, to join the West’s military and political structures, Georgia has to upgrade itself in line with its Euro-Atlantic aspirations: educate its population, develop the economy, and, last but not least, address evident deficiencies in democratic governance.

Developing the public education system

Since 2003, Georgia has made tremendous progress in eradicating corruption in its education system. This success, however, did not translate into quality improvements, as reflected in Georgia’s lackluster performance in international science and math tests, such as PISA and TIMSS. The teaching profession is among the least respected, failing to attract the best and the brightest. Public schools and universities are rigidly regulated by the state, but are shielded from social pressure and competition; teacher unions and academic elites stand united against structural changes. With private schools catering for the rich, the Georgian people are increasingly divided into haves and have-nots, with little social mobility and no equal opportunity at the start.

Radical reforms are long overdue. Such reforms should include increased spending on education at all levels; differentiated teacher compensation; greater autonomy for individual teachers and institutions; a special program of incentives to recruit young teachers willing to work in remote rural locations; and last but not least, international and social partnerships to help Georgian schools and universities implement new teaching methods suited for the 21st century, such as problem-based learning and the ‘flipped classroom’ approach.

Developing the economy

Georgia’s economy was growing rather rapidly in recent years, yet, this growth was far from inclusive, resulting in poverty and very high levels of inequality. Almost a half of the country’s population survives in primitive agriculture; a large share of urban population is unemployed or self-employed in low-productivity services; only 15% of Georgia’s total population are officially employed. With so many people out of the modern labor market, the Georgian economy cannot catch up even with the least developed countries in the EU.

To get out of this predicament, Georgia must implement bold industrial policies, providing incentives for, and coordinating, private sector investment in specific sectors of the economy and geographic regions. This is how Georgia developed the city of Batumi and the mountain resorts in Svaneti and Gudauri. This is how it could start new manufacturing activities with the potential to absorb workers stuck in subsistence agriculture and primitive services. The result would be higher levels of income and economic prosperity for all.

Developing democratic institutions

So far, Georgia’s democracy has been handicapped by a lack of genuine competition, ranking first on the Tbilinomics Index of Political Monopolization among all NATO member states! Georgia’s electoral system allows for an easy emergence of dominant ruling parties that tend to ignore the due political process, public and expert opinion.

Georgia has to urgently abolish single-member districts and introduce voting on nation-wide party lists. By doing so, it would take a major step towards a healthier situation in which parliamentary elections produce coalitional governments based on compromise rather than outright domination, a situation in which major policy choices are properly discussed and contested. Operating in a more competitive environment, political parties will be forced to present their views on issues that genuinely concern Georgian people – jobs, social security, education, minority rights and the environment – as opposed to cheap blame games we have seen them playing on biased television channels in recent months.

* * *

By addressing these interrelated challenges, the Georgian government will acquire the confidence to stand its ground and engage its people in the breakaway territories. It will be able to think in a more flexible way and put on the table solutions that are both feasible and politically acceptable for all sides in the conflict. A more confident Georgia may also be able to mend fences with all of its neighbors while at the same time joining the West’s political structures and security arrangements, such as NATO.

About the author:

Ekaterine Gasparian is a recent IR graduate from the International Black Sea University. She is currently a Communication Specialist at Tbilinomics Policy Advisors. This article was submitted for consideration in the Essay Competition “NATO, Georgia and current security challenges: the 2018 Brussels summit and beyond” organized by the Bulgarian Embassy to Georgia.

By Ekaterine Gasparian