The Fate of the Gray Area in Europe

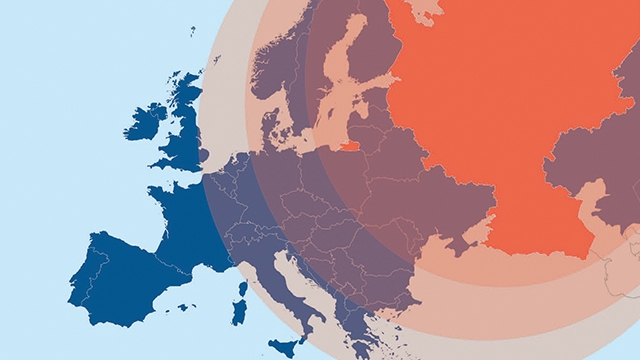

There is a considerable territory between Russia and the European heartland. It runs from the Scandinavian peninsula in the north to the Black Sea in the south. These lands include Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Belarus, Ukraine, Moldova and the South Caucasus states, and can be provisionally called a “gray zone”: lands where Russia and Western/Central European states have clashed militarily for hundreds of years.

If we look at the history of last several centuries, those clashes were often conditioned by military goals: Russia did not want Western states be influential along its borders or Western states, fearing Russia's size, tried to prevent the Slavic state's domination over Central Europe.

However, though these military confrontations are indeed important, they overshadow economic developments on the ground in the “gray zone”.

Let us for a minute take a look at the global context. European civilization, once it attained economic and most of all technological superiority, started to export it to other continents via the oceans. France, Great Britain, Spain, Portugal and others did little to extend their influence to the “gray area”. There was the invasion of Russia by Napoleon in 1812 or the Crimean War (1853-1856) when the western Europeans were operating along the Russian borders, but their interest was mostly military – to contain Russia – rather than the spread of economic influence.

For the westerners, the lands which today constitute that gray zone were not interesting economically and were very hard to reach geographically. Moreover, their geopolitical focus was elsewhere, across the oceans, in Africa and Asia. As a result, Russia, for centuries, was able to operate quite successfully from Finland to the Black and Caspian seas.

Only with the creation of unified Germany, did Russia see a real economic threat to its western territories. And this matters a great deal, as in the long term Germany's economic power will make a difference.

But with the two world wars, where western Europe, along with Germany, lost its pre-eminence, they started to think about unifying Europe. There was also a change in the geopolitical outlook: moving eastward. This involved systematic attempts to spread economic influence in the gray area, particularly seen since the break-up of the Soviet Union. Western European economic influence was soon reaching deep into what Moscow considers as its sphere of influence.

While these days many Russian politicians and their western counterparts view the battle in the “gray zone” a military one, on the ground it is economy which matters. As long as direct military conflict is unlikely to happen, populations even in the most pro-Russian countries, such as Belarus, are starting to gradually move away from the Russian world.

In summary, the late 20th century, the world saw a fundamental change in Europe's geopolitical outlook. For centuries, the continent had been extending outwards via the oceans, to various territories in Africa and Asia. Little if anything was done to attain economic predominance in Eastern Europe, where the border with Russia was. This process is now reversed: it is clear that the only geographic avenue for Europe's projection of power is in the Easternmost parts of the continent: the very gray area I mentioned above. There might be troubles along the way, such as we see nowadays, when talks on enlargement of the European Union are effectively stalled.

However, it is likely to be only short-lived: in an age when the US still dominates the world’s ocean, the only route for Europe to gain larger economic and military say lies eastwards - the route which is also geographically convenient as it passes over the East European plain to the Ural mountains.

This explains why Russia is unable to withstand the European pressure. Poor economic capabilities minimize Russia's chances to retain even culturally close Ukraine. Some signs of Moscow's inability to control Belarus are also visible.

From this perspective, there are historic opportunities for Georgia. For centuries, Georgian kings were active in searching for European economic and military support for the country. Most of those attempts failed, beaten back by western European disinterest. But with this geopolitical reorientation in Europe, there are a lot of opportunities for having European economic and military structures spread to Georgia. This will take years if not decades, but it is important to view the whole process from a long-term perspective.

By Emil Avdaliani