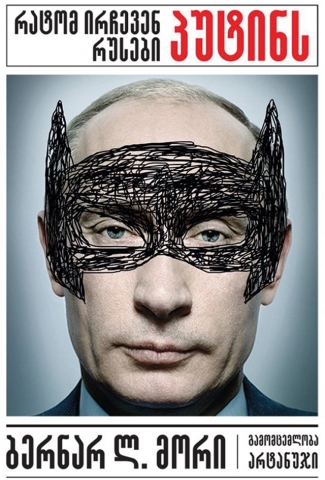

“Has Power Gone to His Head?” – Bernhard L. Mohr on Putin & His Russia

Interview

In an inaugural interview of the new GISP series, titled “Insights on Putin’s Russia”, the Georgian Institute for Security Policy chatted with Bernhard Mohr, author of the acclaimed “Why Do Russians Vote for Putin?”, which has also been translated into Georgian and published by Artanuji Publishing House. Himself a Norwegian, Mohr spent considerable time in Russia, trying to solve several puzzles pertaining both to the country and the leader it is under.

“Russia is a very big country and the biggest part of the Russian population is working class, living in cities that are huge in comparison to most European cities but relatively small in Russia, cities between 300,000-1 million inhabitants. This big group of working class people has quite a conservative way of life; their access to information is relatively limited because they don’t speak foreign languages, and they mainly watch State TV, which is very controlled. The big state media, they don’t do journalism, they do propaganda. To a certain extent, their voting for Putin is understandable. What is more puzzling is that the same applies to the urban middle class, constituting around 25% of the population. These are people with higher education that have traveled a lot in Western Europe, that have access to different sources of information, such as internet and are able to take different perspectives. I was interested in trying to understand why these people by far and large support Putin’s regime. I’ve come to see that after the Crimea annexation, their views somehow changed: even people that were in the liberal camp and were critical of Putin suddenly became fans of his policies and supportive of the regime. That’s why I wanted to write this book. In researching for the book, I did a lot of interviews with middle class Russians living mostly in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, but I also went to South Russia, to Rostov-na-Donu and Taganrog. At that time, in 2016-2017, the whole Crimea annexation and assertive foreign policy was tremendously popular, and almost everyone in Russian society supported their president in his aggressive, challenging foreign policies.”

Do you have any idea why? What is that secret element that drives them into a Putin worshipping frenzy?

When I did the interviews for my book, a lot of people said, ‘we realize that what we did in Crimea was a breach of international law, but it was still the right thing to do. Crimea was traditionally Russian and we have the right to be a dominant player in this part of the world.’ And this was a sentiment even felt among the best educated. Partially, I think this can be explained by some sort of post-imperial syndrome that Russian people seem to suffer from; where people cherished the fact that the Soviet Union was a big international player the USA had to take into account. After that came the period of chaos under Yeltsin, and now people had to watch Russia again – for many, this proved to be a very comforting, soothing perspective. During and after the Crimea annexation people did not go to TV to get news, they went to TV to get appreciation or comfort. There’s background rationale for this strong effect: when Putin came into power in 2000, and between 2000 and 2012, the Russian economy grew extremely fast, driven mostly by oil prices, but in 2011, 2012, people came to the realization that this economic wonder would not last forever. In 2006-2007, we thought we would catch up with western countries and then realized, no, this wasn’t going to happen; so we needed something else, and this was the next best thing.

And enter Georgia in 2008, a classic case of a small victorious war.

True. And then 2014, a bigger victorious war. From 2015 – 2017, there was this rally around the banner because of the Crimea annexation; there was the narrative that Russia was entrenched by NATO bases all around the country and NATO was expanding. If you read the security documents, this is what they state. It created the icon of ‘enemy’ that is extremely convenient to manipulate Russian people with.

If the fascination with Putin is tied down to mentality and nationality, what good can come from the West’s continuous attempt to convert Russia to liberalism?

This is a big question; I think the premise is only partially right, I think the more conservative side of Russian society is happy with a somehow authoritarian leader but there’s again 20-25% of the population which is well educated, this part of population is not entirely lost to the West; I am convinced about this because it’s my environment, I was there, I talked to people; since 2017 that effect has diminished. There’s a need for something else; there are very clear indications from social surveys showing that younger adults today, they don’t believe much more in the main narrative of Russia being entrenched by NATO and so on.

In your book you seem disappointed that these educated people, once friends, have changed their values. Is it possible that these young people you are so hopeful about will also be thinking that way in ten years’ time?

It’s a key question, and there’s no guarantee. I still think Russia might develop in a more democratic direction after Putin, but at the same time, Russia’s foreign policy may continue to be assertive. Even if you have a more open and democratic society, you may still have quite a hostile foreign policy. But what I see is that younger people in Russia will not accept living in conditions that are severely worse compared to people of their age in the rest of Europe; I think they expect to have the same opportunities. Today’s twenty-year-olds don’t watch TV: they read foreign news; what they take in is from internet, and they know how the world works and aren’t as easily duped.

Is Putin the architect of modern Russia, or does he merely give people what they want?

I think it’s a mix. The Kremlin responded to changes in sentiments among the population; but also went to great lengths to centralize power, to get rid of alternative centers of power; immediately taking control of TV. Also, the courts don’t act independently, which was key to Putin from day one.

You said that Russia might develop in a more democratic direction after Putin. But isn’t “Putin forever” a more likely scenario now?

Until this spring most people expected Putin to step down as president when his fourth term ends in 2024. Some experts suggested that he would stay close to power, but in a new role, for instance like Nazarbayev in Kazakhstan, who heads the State Council. But now, with the suggested “nullification” of his two last presidential terms, Putin can stay in power until 2036.

It is hard to reveal Mr. Putin’s inner motivation for this move: Has power gone to his head, or are he and his closest allies truly convinced that his being in charge is vehement to Russia’s modernization? What we can say for sure, is that this step once and for all takes Putin’s Russia out of the category of “managed democracies” and into the “autocracy” category.

What is the most feasible and effective policy to pursue with Russia? Is a dialogue-oriented policy realistic, or is the red line policy the way?

In Norway we try to do a mix of both. We collaborate productively with Russia in fields where we as neighboring countries have to work together, at the same time fulfilling our obligations as NATO members. Norway has been part of NATO since 1949. The Russo-Norwegian border was established in 1826, and there have never been any actions of war between the two sides. Russia and Georgia is, of course, a completely different history. Also, in terms of trade, I guess Georgia is dependent on Russia, whereas Norway trades little with Russia. But Russia has its own troubles too: the biggest challenge for Russia is its economy, which is not growing. People are getting fed up. What people in Russia now ask is whether the state is interested in dialogue with the rest of the world. Russia knows it cannot develop its economy on its own, that it has to work more closely with its western partners. Small victorious wars like Syria, Georgia, and Crimea cost them a lot of Rubles.

Is there a danger Russia might win the fatigue game because the West is divided on the subject of what to do with Russia, and issues like Georgia and Ukraine might become bargaining chips?

I don’t think so, for two reasons. One is that Russia needs the West much more than the West needs Russia, and the second: the West has so much on its plate right now, we have to take care of ourselves, we don’t have time to care much about Russia. It’s about the status quo: keeping sanctions and demanding that Russia behave and live up to the Minsk agreements.

What's your take on Russia's “malign influence” in the neighborhood? How tangible is the Russian influence in Scandinavia?

I write quite a lot about this in my new book. I don’t foresee any Russian military aggression towards Norway, but what we can expect to see is disinformation campaigns; when Norwegian secret services report on security threats to Norway, they always mention one of the biggest threats as being cyberattacks from great powers, Russia and China, and there have been quite a few attacks.

What do you think is the biggest danger that comes from Russia and Putin, and what would you envisage as an effective instrument for countering that threat?

The Russian side doesn't believe much in collaboration with the West. They see the world as being embroiled in a constant fight between big powers and what we call the zero sum game: it doesn't matter what the other side gets, you just have to ensure that you get most. Russia has shown its willingness to take whatever measure to achieve its goals, using its military in Georgia, in Kiev; using hybrid measures and social media to influence the political debate in Western countries. I think the greatest threat is that in this situation, there's no faith in the other side.

By Vazha Tavberidze