Redjeb Jordania on What His Father Would Think of Georgia Now

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW

Last week, Georgia celebrated the 102nd anniversary of the Democratic Republic of Georgia- independence was declared on May 26, 1918, and the government led by Noe Jordania until February 25, 1921, when Soviet troops annexed the fledgling First Republic. Jordania’s government left the country and lived in exile in France, where they continued to work tirelessly towards restoring Georgia as an independent state.

GEORGIA TODAY, via GT LIVE INTERVIEWS, met the 98-year-old son of the First President and Head of the Democratic Republic of Georgia, Redjeb Jordania, who is based in New York with his family, but who has been self-isolating in Florida during the coronavirus pandemic, close to the sea- one of his life’s greatest loves.

You grew up outside Georgia. How connected do you feel with it, and how do you keep up relations?

I was born in Paris in 1921, just after my parents were obliged to come to France after the [Russian] invasion. I grew up in Paris. Upon reflection, it was a life typical of children of political émigrés, which are not the same as migrants: we expected to be there only temporarily. I went to French schools, spoke French, but my real friends were Georgian children. My connection with Georgia was through them, and my father, and through being brought up in Paris in a Georgian colony. The first time I went to Georgia was in 1990. Before that, it wasn’t possible, but Glasnost opened up that possibility. After that, I was in Georgia many, many times. In the 90s, I saw the situation there and thought: what can I do to help? I decided to help Georgia connect with the Western world, which seemed to be what they wanted most. And my way of doing it was to organize summer courses in the American-English language. We recruited a bunch of American volunteer teachers and ran it for about 6 weeks each summer over several years. After that, Georgia got better organized and the teaching of English was made official, and they didn’t need me anymore. I always kept contact with Georgia and the Georgian colonies in the US and Paris. Now, I’m 98 years old and I no longer have those childhood friends.

My Georgian is very shaky. My mother was Russian. My parents met in Paris in 1902, and at home would speak mostly in Russian together. My father would speak to me in Georgian, my mother in Russian, and I would always answer them in French.

Tell us about Noe Jordania, your father, and what he achieved for Georgia 102 years ago.

Before 1918, there was, so to speak, no “Georgia”. For centuries, it had been splintered into kingdoms, until the Russians took over. My father wrote in his memoirs that at the end of the 19th century, the Georgian concept of “belonging” was to belong to one’s family, one’s village and most of all to one’s province, but the concept of Georgia as a country was practically non-existent. It took a lot of work by many Georgian patriots, and at the grassroots by the social democrats, to recreate a concept of Georgia. The 1918 creation of the Georgian First Republic was the creation of a modern Georgia after centuries of disarray.

What was life in Tbilisi and Georgia like in those three years of independence?

In the times of Noe Jordania, there was a big upheaval; civil wars all around, the Ottoman and Persian world disappearing. Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk and abandoned 500,000 Russian and Polish troops on the border between Georgia and Turkey- all these soldiers had to be fed and repatriated. There were fights all over. But life in Tbilisi was like an “island of relative peace,” very active both politically and artistically. A lot of Russian artists descended on Georgia as a haven of peace, and you have to remember that in those times, Georgia was an agrarian society, no industry to speak of. Peasants made the country work. The creation of the first social democracy in the world relied greatly on the peasants, and that’s how life was.

In the times of my father, there was greater production that I have seen in my lifetime. When he was born, there was practically no electricity. No cars. The most advanced thing was the steam engine and gaslight. By the time he died, we had radios and television and everything. According to all my Georgian friends, it seems that life in Georgia consisted mostly of supras, though the word we used back then was “keipi”.

What was the most difficult aspect for your father being away from Georgia?

I realized only later that it was the cultural aspect of being away [that was most difficult for him]. In the 1920s, everyone expected the communist system to collapse. Wealthy Russian émigrés would spend money like water because they expected to be able to go back and recuperate their riches. As we know, it didn’t happen, and the Soviet Union continued for a long time. My father was always struggling and working to protect Georgia on the international level, but after the end of World War Two, he realized the Soviet Union was there to last. At that point, he advised all those Georgians who were able, to return to Georgia. A number of them, including the parents of some of my friends, did so, and it was ok for them.

What was your father like as a person?

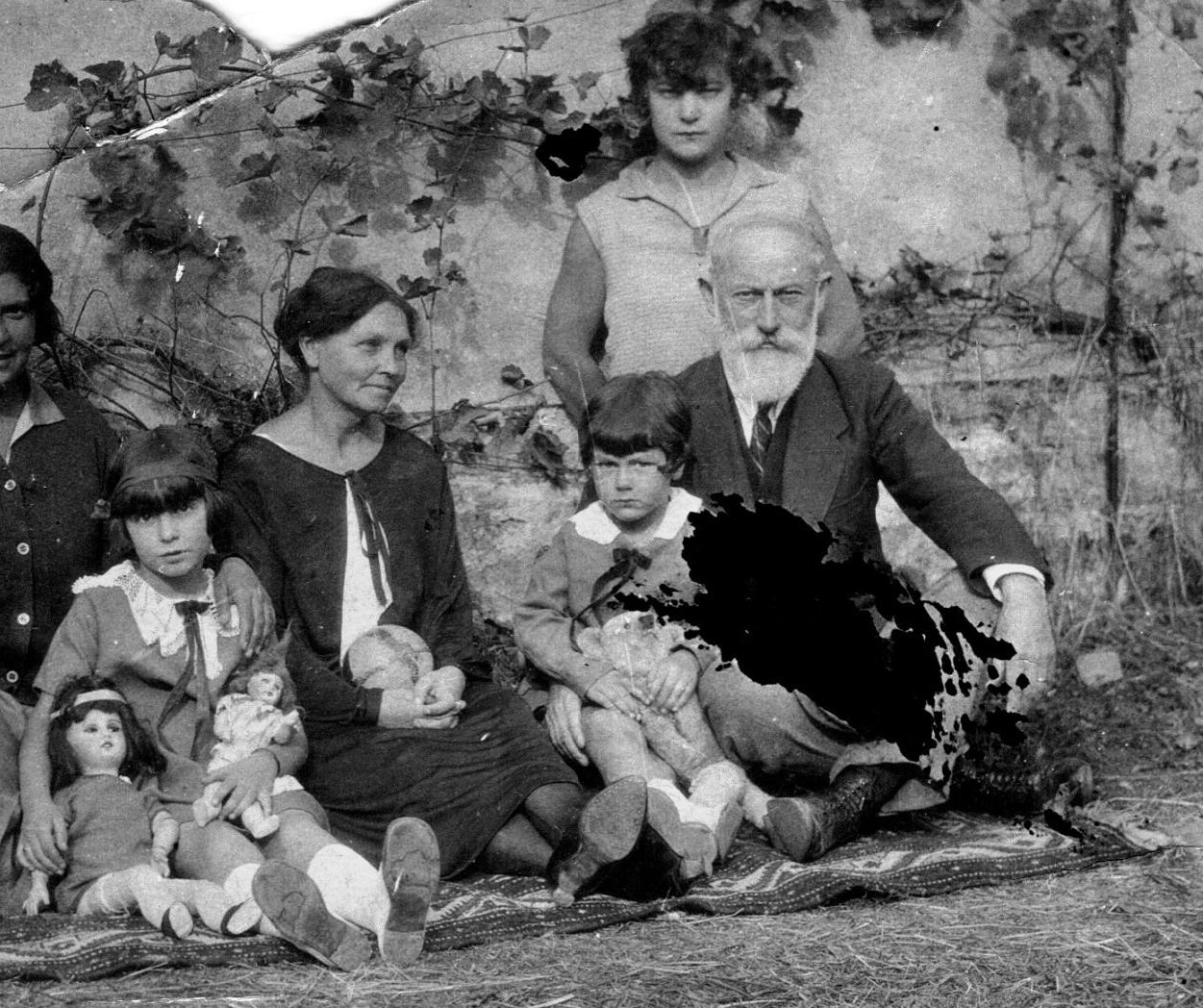

He was 53 years old when I was born, therefore he was more like a grandfather than a father. He tried to bond, but there was no playing in the fields- fathers playing with their children was not the done thing back then, it’s a fairly modern concept. He was a rather distant person [to me], though, even as a child, I knew he was someone important, because all the important people would come to visit him, deferring to him, and naturally, I was greatly impressed.

Did you grow up wanting to go to Georgia?

No. There wasn’t even the possibility of it. And somehow, I felt I was in Georgia. We had Georgian food, Georgian songs, Georgian meetings, Georgian friends. Outside of Paris is the Leuville Estate, given to the Georgian government by France, and we all spent almost every weekend there. There was a Shevardeni club at a gymnasium in Paris, and we kids met there every Tuesday night.

Do you think your father would be happy with where Georgia stands today in its political mentality?

It’s difficult to answer for him now. He was not against a good relationship with Russia. He knew that Georgia could not stand on its own feet without strong alliances, and we have to realize that in the geopolitical reality, Russia is next to us and is going to be there forever, so, we’d do better to have some sort of different relationship with them. It’s already 30 years that Georgia is independent. It’s the longest the country has been independent since the times of Queen Tamar. Altogether, I think my father would say Georgia is doing pretty well, despite the difficulties.

Download ‘All My Georgias’ by Redjeb Jordania from amazon.com.

By Katie Ruth Davies