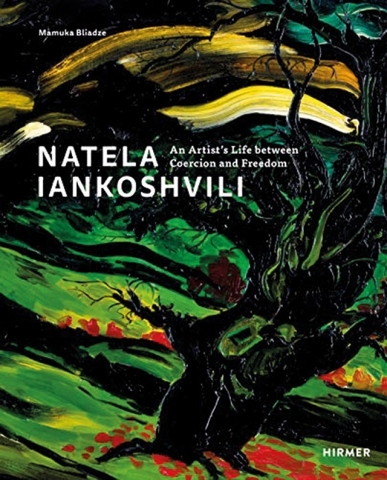

Natela Iankoshvili – An Artist’s Life between Coercion & Freedom

REVIEW

A new book dedicated to the Georgian painter Natela Iankoshvili has come to the attention of the quarterly supplement of the German newspaper Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, “Fresko” (N1, 2020) and so I will begin with this joyous event.

As Fresko’s resident critic Thomas Zuhr writes: “In many cultures around the world, the color black is often associated with sorrow, suffering and death. At the same time, however, it also has associations with intellectualism, refinement and religious devotion. Two masters of the color black, Kazimir Malevich and Pierre Soulages, say that black is actually the most dynamic color and as such their works take inspiration primarily from this shade. The legacy and works of the Georgian painter Natela Iankoshvili (1918-2007) shows us that black can have a ‘lightness’ to it, making it as diverse as any other color. As such, she exclusively uses a black background for her canvases. In Georgia, this painter has long been considered a national treasure, but it’s only in the last few years that she has gained international recognition, in the same way as that handful of other painters who continued to carve their own artistic path and express their own beliefs during the artistic dictatorship of the Soviet period. Here, we should also mention that Iankoshvili is a great master of the use of black. She created more than 2000 canvases, and her particular strength is in depicting landscapes. Her brushstrokes are incredibly expressive and she manages to lend an inextinguishable energy to the color black.”

Natela Iankoshvili – An Artist’s Life between Coercion and Freedom is the name of a book recently printed by the well-known German publisher Hirmer in separate German and English versions. This book introduces an artist with a unique biography to a global audience; an artist who rightly deserves to be known well beyond the borders of Georgia and who belongs to that rare breed of painters whose artistic life can truly be called ‘heroic’.

The author is the Artistic Director of the Galerie Kornfeld, Mamuka Bliadze, who dedicated two years to studying the life and times of Natela Iankoshvili, and the difficult period and conditions in which this great artist was forced to live and work. In the first instance, we must point out the book’s brilliantly-chosen title, which immediately arouses in the reader an intense interest in getting to know a previously unknown artist, one who had to battle tirelessly for the right to self-expression.

In his book, the author makes use of the professional opinions of German, English, Italian, American, Russian and Georgian art critics (Marleen Stoessel, Lisa Zeitz, Dennis Goldberg, Gaia Simionati, Alina Cohen, Katharina Rudolph, Savva Dangulov, Olga Velikanova, Gaston Bouatchidze, Eter Shavgulidze), who believe Iankoshvili to be an artist of great breadth and of indefatigable spirit; someone who is able to inspire and delight viewers already well-versed in fine arts. Also included in the book are the recollections of those who knew Iankoshvili personally (Baia Dvalishvili, Soso Chumburidze, Rismag Gordeziani, Vaja Dzigua, Neli Gurgenidze). After reading them, one is absolutely convinced of the artist’s principled and unbending nature, something Iankoshvili had to acquire in order never to bow down before (or be broken by) an implacable Soviet regime.

The book quite clearly illustrates Iankoshvili’s unshakable belief that the human soul is born for freedom and that no earthly chains or fetters can choke it. It was precisely with such faithfulness and unwavering determination that she established her name as an artist that never benefitted from official favor. In her boldness and fearlessness, Iankoshvili’s work places Georgia even more firmly on the world map of painting. If ten-or-so years ago the artist’s name was known only in her homeland, last year Iankoshvili’s works were exhibited next to those of the world-famous artist Meret Oppenheim at the Istanbul Biennial. Before that, she received recognition at high-profile art forums in Berlin, Cologne, Brussels and New York.

As a Georgian, it brings me great pleasure to see Natela Iankoshvili’s star rising, and to see her work gain a new lease of life in the 21st century. At the same time, it’s painful to acknowledge that all of this is happening without the involvement and impetus of Georgia. Instead, it’s Germany that has taken on the task of introducing this foreign artist to new audiences and popularizing her works. This is, it seems, Georgia’s perennial problem; that unless foreigners remind us of how rich a heritage we possess, we are unable to see it ourselves! This has been the case with Pirosmani, Georgian polyphonic music, choreography, cinematography, Robert Sturua and Giya Kancheli.

From the book, it’s very clear that Natela Iankoshvili never bowed down before “the powers of this world”. Her directness and stubborn character only led to an increase in the number of her official enemies during her lifetime. It’s incredible, that already 12 years after her passing, she has not been fully recognized, celebrated and respected in a way fitting for a great artist. It’s unfortunate that during the last 30 years, independent Georgia has been unable to fully re-evaluate the importance of art created during the Soviet period. More unfortunately, it seems that the injustice of the Soviet period is still an integral part of the Georgian mentality.

This is a wholly inadmissible situation, and one which makes it clear that Georgia’s current culture policy is anachronistic. After so long as an independent country with open borders, is it only now becoming clear to us what is of value in our culture and what has been forced upon us? This, too, is the hidden face of corruption and nepotism; we still haven’t started the entirely healthy process of re-evaluating our artistic heritage. For precisely this reason, Natela Iankoshvili remains a marginal artist in her own homeland, whereas in reality she is one of those few Georgian artists that absolutely can’t be discounted and one who fully deserves greater recognition.

It’s evident from Mamuka Bliadze’s book how much of a role Iankoshvili played in developing Georgia’s national culture. She created the largest collection of canvases of any 20th century Georgian artist. For future generations of Georgians, she produced depictions of more than a hundred church buildings, and this at a time when religion was considered a dirty word. Her most valuable contribution, however, is the fact that Iankoshvili changed the face of landscape painting - not just in Georgia, but globally. How can this innovation not be of interest to a new generation of Georgian art critics? I’m fully convinced that they will soon turn to Iankoshvili, study her work assiduously and eventually grant her the place that she deserves in Georgian cultural history.

For the publication of such a high-quality printed text that is also richly illustrated (the books 160 include 66 images), we owe special thanks to the German friends of Georgia - the owners of the famous Galerie Kornfeld in Berlin, Alfred Kornfeld and Anne Langmann, who first visited Georgia fifteen years ago and encountered Georgian painters there. After Pirosmani, it was Iankoshvili’s painting that left the greatest impression on them. In 2012 they held a personal exhibition for Iankoshvili in their own gallery, while the publisher Kehrer published an extensive catalog of Iankoshvili’s works in both English and German.

It doubtless that, just as Michael le-Dantu and the Zdanevich Brothers introduced the world to Pirosmani, Alfred Kornfeld and Anne Langmann performed a similar feat a century later - this time introducing a wholly different wonder in the form of Iankoshvili. The contribution of these two Germans, genuinely in love with Georgia and Georgian art, is truly worthy of note and recognition within Georgia itself.

Mamuka Bliadze’s book, Natela Iankoshvili – An Artist’s Life between Coercion and Freedom, is now available for purchase on Amazon and in Waterstones bookshops.

By George Laliashvili, Art-Critic