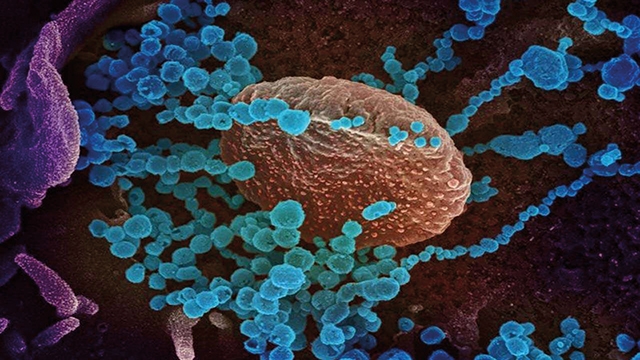

COVID Mutations: To Worry or Not To Worry?

Out of all the 12 months of 2020, December has been the most hopeful perhaps, with vaccination roll outs starting early in the month, first in Britain, followed by Canada and the United States just recently. These Pfizer shots, with 95% efficacy, and the newer Moderna vaccine said to be just as effective, offered a world on edge hope for a way out of the pandemic. Of course, 2020 being 2020 still gave us bumps on the road: first came allergy warnings against the vaccine, and now Britain and South Africa report a mutation of the virus, which is about 70% more easily transmitted. Worried but not surprised, scientists say there are many layers under the surface.

“The fact is that you have a thousand big guns pointed at the virus,” Kartik Chandran, a virologist at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, told the New York Times. “No matter how the virus twists and weaves, it’s not that easy to find a genetic solution that can really combat all these different antibody specificities, not to mention the other arms of the immune response.”

This past weekend, Britain claimed the new, highly contagious variant of COVID had started circulating in England. Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced “when the virus changes its method of attack, we must change our method of defense,” as London and its surrounding areas saw a rapid surge in new cases and the country entered the tightest lockdown since March.

As the news about the new COVID mutation spread, European countries made a move to close their borders with the United Kingdom on Sunday. The Netherlands suspended flights from Britain until January 1. While Germany is limiting travel both from Britain and South Africa, Italy has suspended air travel to the UK, and Belgium imposed a ban on train and air arrivals from the country.

As Spanish officials addressed the European Union to draw up a coordinated response to banning flights, in total more than 40 countries banned UK arrivals.

UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock has warned that the new mutation of the virus, which may be up to 70% more transmissible, is “getting out of control.” There is no laboratory-backed evidence of this transmissibility, however. The Health Secretary is also worried about the still-packed trains in England, calling them “clearly irresponsible.” The number of policemen in railway stations is to increase so they can check that passengers are taking their journeys for essential reasons only. The stringent restrictions might be in place for the next few months, Hancock warned.

South Africa has seen the same version of the virus. Scientists there analysed the genetic sequences of COVID patients taken from mid-November, detecting a mutation similar of that in Britain in up to 90% of the samples. Yet, scientists in neither Britain nor South Africa rule out the chance that some of the newly-acquired transmissibility might be caused by human behaviour.

The fact that the virus is mutating comes as no surprise: researchers have recorded thousands of tiny modifications in the genetic material of the coronavirus. For it to survive, the virus needs to shift shapes so that the immune system will not be able to detect it or defeat it, but as the experts have said, COVID simply does not need such a big alteration so soon. “It would be a little surprising to me if we were seeing active selection for immune escape,” said Emma Hodcroft, a molecular epidemiologist at the University of Bern in Switzerland, talking to The New York Times.

“In a population that’s still mostly naïve, the virus just doesn’t need to do that yet,” she said. “But it’s something we want to watch out for in the long term, especially as we start getting more people vaccinated.”

Hodcroft says that immunizing about 60% of the population within about a year, and preventing the disease spread as much as possible, will help minimize the chances of the virus mutating notably.

Influenza, which is considered a fast mutating virus, needs five to seven years to change its genetic code so significantly that it completely escapes immune recognition. Further, a recent report claims that common cold viruses evolve to escape the immune system, but need many years to do so.

Despite this, the scientists perhaps now more than ever need to watch closely how the virus evolves so that they are able to spot if it gets an edge over the vaccines. Flu viruses for one are regularly monitored, and its vaccines are updated after each significant mutation. According to Trevor Bedford, an evolutionary biologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, the same should be done for COVID.

“You can imagine a process that exists for the flu vaccine, where you’re swapping in these variants and everyone’s getting their yearly COVID shot,” he said. “I think that’s what generally will be necessary.”

Sources: The New York Times, The BBC

Image source: DNAindia.com

By Nini Dakhundaridze