The Surreal World from the Eyes of an Ushguli Artist

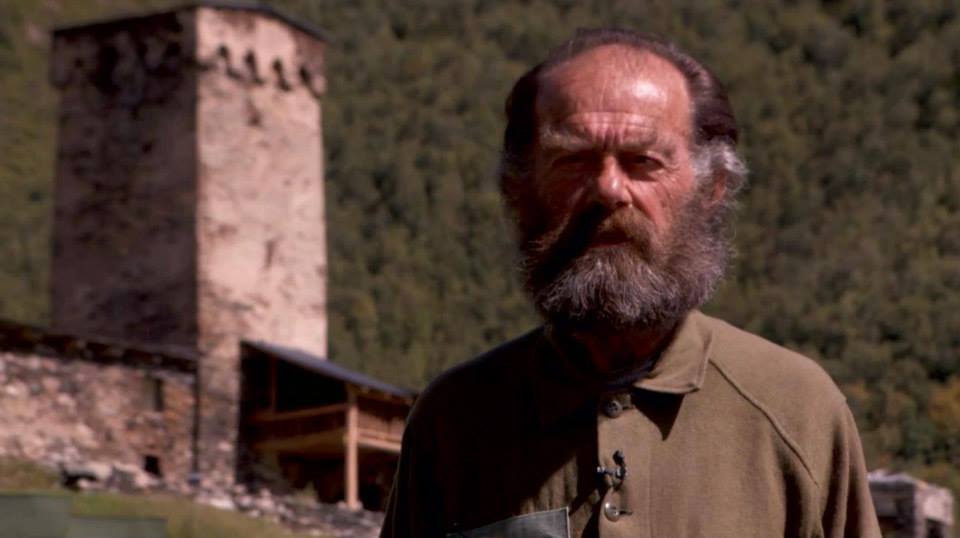

Ever heard of Ushguli? It’s the highest inhabited place in Europe and Georgia’s most remote region of Svaneti. Among the houses that sparsely top the ragged terrain, there is one that serves as home to a mysterious man – 72-year-old painter extraordinaire Fridon Nizharadze. In the village named Chazhashi, which is part of the Ushguli community, life is an uphill battle: electricity and water shortages are constant challenges and the place is almost inaccessible in winter due to disastrous road conditions. It’s probably the last place you’d expect an impressionist artist to pop up. Yet the man in question grew up and still lives here, in this isolated place, with little to no interest in the benefits of our tech-savvy era. He doesn’t even use a cell phone, yet his brush is responsible for creating world-wise, diverse and progressive works of art. Fridon’s bright, scintillatingly colored artworks are laced with Georgian motives and abound with allegories, symbolics and hidden meanings, and there is an unmistakable ubiquity to all of them – that of a master who learned his trade without tutelage. Some call it psychedelic surrealism, yet his vision is undoubtedly yet another stepping stone in Georgian art.

As often happens, the reclusive painter is virtually unknown and we at GEORGIA TODAY, fascinated with what we saw, decided to start setting this regrettable fact to rights. As he himself states, he never had an exhibition and he paints for his own pleasure. We spoke to Fridon’s brother Teimuraz, who lives with him, and asked him to share the painter’s story, since Fridon himself is something of a hermit and rarely interacts with others.

“My brother started drawing before he started school. He used to head outdoors, sit there alone and draw landscapes. Bela Berdzenishvili, a fellow painter, visited Svaneti once and when she saw Fridon’s paintings was so amazed that she gifted him his first palette. He’s self-taught, but later enrolled at the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts. He spent three years serving in the army in Kazakhstan in the 1970s and upon returning, entered the art academy. He was always a breed apart from everyone and still is. After graduating in 1973, he chose not to stay in the city and returned to his village. He used to be a guardian of the icons and other valuable items kept at the 6th century Church of Christ in Chazhashi village - listed among UNESCO heritage sites - before they were moved to the museum. He is somewhat of a philosopher, too, chiding us locals all the while for ‘only thinking about growing potatoes.’ When we were young, this wasn’t exactly a behavior that was encouraged by the government. His negative opinions regarding Lenin and the Soviet Union didn’t help and he sometimes found himself in trouble with the Soviet government. To his credit, though, never in his life did he renounce his belief – he is stubborn to a fault and I think this helped, too.”

Fridon was once placed in an asylum in Tbilisi.

Yes. He spent several months there and, as he himself claims, was drained of great amounts of blood and given lots of pills. The way he behaved, lived and painted was not acceptable to the general standards established by the communist government. Subsequently, everyone perceived him as a madman. Those were, as he calls it, dark ages in our country. Dissenting opinions were prosecuted and regarded as a mental disorder. Sometimes even Fridon’s own family members, including myself and relatives with whom he stayed in Tbilisi, could not understand what he wanted to convey through his paintings. For instance, when he drew a man with a single eye, similar to a cyclops, people would react negatively and say that it wasn’t normal. We wanted him to draw standard things; personally, I told him to paint ordinary towers of Svaneti - something that we could understand - instead of the strange things. Now I regret saying that, honestly. He would always answer that he couldn’t stop the unusual ideas coming to his mind day and night; he said he had to release them by transferring them onto paper. And then he went and painted collapsed and ruined towers and there were some who took it as a very bad omen. People didn’t really appreciate it. This hostility left a mark on both his life and personality. Today, he is a well-respected person and everyone in the village knows him. He never exhibited his works, though; he thinks it’s expensive and a hassle.

When did his paintings catch the attention of tourists?

His paintings were discovered in the 1990s. We hung some banners along the nearby roads indicating the location of our house and have been hosting tourists ever since. Tourism became our main source of income. In addition, we sold Fridon’s paintings very cheaply. Now we have only a couple left, and we aren’t selling them anymore. Tourists love Fridon’s works. Unfortunately, my brother doesn’t have the same energy to create new works of art as he had before. However, recently he was sent new pencils and drawing utensils from Poland that somehow gave him a bit of stimulus to create small works. He is a bit apathetic now - life treated him cruelly and now he has lost interest in almost everything. Most of the time he just sits there, sad, lost in his thoughts, but there are glimpses when he is in good spirits. He works at the local museum as a guide and earns his living that way. We have a few heads of cattle, but tourism and Fridon’s salary serve as the main source of income. Although it’s very hard to live in such a remote place in the mountains, I would still take it over life in a city any day. And if I dare to address the people responsible through your paper, the local population would be grateful if the government paid better attention to such villages and helped us improve our living conditions.

Lika Chigaldze