How About Just Making America Better?

When Ronald Reagan won the presidency in 1980 and went on to redefine American conservativism, his message was hopeful. The country was in a temporary rut, but a brighter, better future was within reach. The State just needed to remove artificial “barriers to progress” and let the individual reach his or her full potential. That kind of message doesn’t resonate these days. Many voters are cynical and pessimistic. They see America as a country on a downward slide. They’d rather hide in an idyllic past than leap into an exciting future.

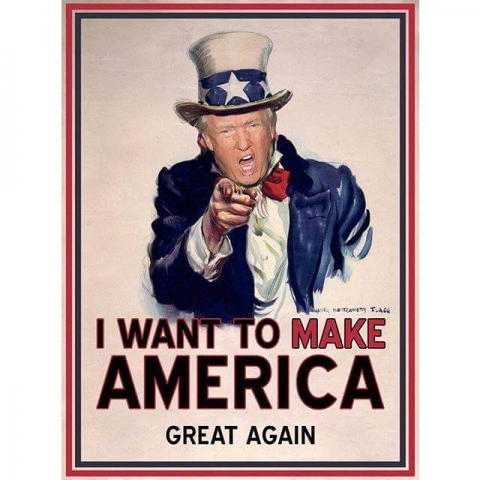

That’s essentially the message promoted by Donald Trump, the man who won the Republican Party’s presidential nomination with help from a nostalgic slogan: “Make America great again.” Things are bad now and they were good before, so we should have more of the old and less of the new. Before we ridicule Trump and his supporters, however, we should admit that people on both ends of the spectrum and from all walks of life are fed up with what they see as a dysfunctional political system and a floundering economy. “Make America great again” may belong to Mr. Trump, but simply the word “again” does enough to explain America’s current politics. Other politicians are finding success with similar messages. Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and Bernie Sanders don’t share Trump’s longing for a whiter, more masculine era, but they often speak about an economic paradise lost.

In The Fractured Republic: Renewing America’s Social Contract in the Age of Individualism, esteemed conservative writer Yuval Levin diagnoses nostalgia as a disease afflicting the Republican Party and the country. He finished writing it while Trump’s nomination still sounded like an absurd fantasy, but his analysis has become only more relevant. The Left wants to turn the clock back to 1965, and the Right wants it to be forever 1981. In Levin’s words: “The Right wants unmitigated economic individualism but a return to common moral norms. The Left wants unrestrained moral relativism but economic consolidation. Both will need to come to terms with some uncomfortable realities of twenty-first century America.”

That starts with accepting that the post-war order is dead and gone, and admitting that it died for real reasons: the global conditions that buoyed America’s booming industrial economy no longer exist, and the era’s stifling social conformity got old a long time ago. The large factory has been replaced by the tech startup. A single mass culture has given way to countless subcultures, smaller groups of like-minded people that often transcend local communities. The bargaining power of workers has been replaced by that of the almighty consumer. And amidst all that deconsolidation, the federal government has gotten bigger and more centralized. As an ideological conservative with a preference for bottom-up solutions, Levin spots a contradiction. Rather than reforming public services to make them more local and more flexible, and thus better able to meet the needs of citizens in an unbundled society, the Democratic Party is focused on finding top-down solutions to what they consider to be nationwide problems.

Levin’s solution is to accommodate America’s deconsolidation—to “seek diffusing, individualist remedies for the diseases most incident to a diffuse, individualist society”—by relying on the principle of subsidiarity. That means handing more power to the political bodies closest to the problems that government is working to solve. Examples include giving state and local governments more control over how tax dollars are spent, combatting soaring tuition costs through deregulation rather than by expanding federal student aid programs, and fixing America’s failing public schools by presenting parents with more choices. It also means reviving mediating institutions such as places of worship, community organizations, and charities; the institutions that stand between families and the State, and in Levin’s view the ones most capable of addressing the problems facing America’s fragmented society. By restoring horizontal bonds, Americans will be better equipped to live fulfilling, successful lives in an era when confidence in the federal government is historically low.

These ideas aren’t original, but Levin presents them with rare insight and precision. Even more so, he makes a compelling case for why America should wake from its nostalgia and instead make the best of what the present has to offer. In his view, there is a lot. Americans have more choices than their parents and grandparents even dreamed of, and the country’s economy is still dynamic, if much less secure. He focuses on building a better future, not longing for an idealized past.

This book also has shortcomings. Levin is insensitive to concerns about income inequality, and only briefly mentions the (understandable) reasons why many Americans are averse to the kind of localism he prescribes. Many minorities, for example, see subsidiarity as paving the way for prejudiced local officials to deny them equal access to public services and legal protections. As a social conservative, Levin takes for granted the justice and utility of the traditional norms that govern private morality. Still, he’s one of the few intellectuals from either party willing to take responsibility for America’s problems—and to admit that his party needs to undergo major reform in order to become part of the solution.

By Joseph Larsen