‘The English Teacher’ Highlights Failings of an Education System

CineClub, in partnership with CinéDOC-Tbilisi and in advance of the CinéDOC-Tbilisi festival which kicks off this month, screened the well-appraised 2012 documentary ‘The English Teacher’ at Amirani cinema this Monday.

The story follows Bradley, a South African who has volunteered as part of then-president Saakashvili’s ambitious plan (‘Teach & Learn with Georgia’ [TLG]) to have every citizen of Georgia speaking English. The program is widely known to have been a spontaneous and little-thought-out endeavour based on the principal of “speak English and you can teach it!”

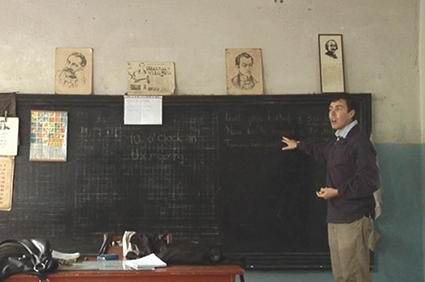

And so the enthusiastic youth came in their hundreds to be shipped off to random isolated villages in worst cases, semi-civilized regional towns at best. They were given the National Curriculum coursebook and, with the translation help of the resident English teacher, were told to teach with it.

They were also expected to passively “retrain” the resident teachers in modern and unconventional methods, bringing new life and motivation to the tired Soviet classrooms. But, facing staunch traditionalists, some of whom had been teaching for over 25 years in one and the same style (and probably in one and the same classroom), and severely uneducated children with little-to-no dreams, many of the untrained and psychologically under-prepared teachers fled on the first flights home.

“What do you want to do when you finish school?” Bradley asks a group of 15 year olds who he has been teaching for some months. They look at him blankly until the teacher translates. Then they look at him with half-smiles. One girl stands up. “Go to Tbilisi,” she says with a shy giggle. “What do you want to do in Tbilisi?” Bradley asks. She shrugs and sits. Other pupils repeats the exact same “dream,” though it’s clear they have no idea what exactly “going to Tbilisi” means- perhaps education, streets paved with gold and endless opportunities to escape the humdrum agricultural-unemployment cycle. Some children don’t even offer Bradley that.

“Where would you like to go outside Georgia?” he asks them, changing tack. He shows them a map of the world but they are unable to identify Georgia let alone stick a pin in possible future travel destinations.

Despite knowing little Georgian, Bradley tries to inspire them with song, with music (bad internet connection and no working electricity socket in the classroom for speakers made anything beyond blackboard and book nearly impossible) and with energy. But over the school year we see his energy and enthusiasm dim.

“I don’t feel like I’m making a difference here. It’s a joke,” he tells the documentary makers following a discovery that his resident colleague is faking English-language test results- tests which, as far as Bradley knows, the children never even took. He looks decidedly glum as he is forced to sign graduation certificates that few children truly deserve.

In an interview after the screening, director Nino Orjonikidze said that it was never her intention in making the film to create a scandal or cause any of the teachers shown to lose their jobs.

“I was curious about the new TLG system. I wanted to open my people’s eyes to the reality of the education system here- not least those so entrenched in that system they are unable and at times fearful to change.”

It is precisely that fear of change that resulted in the first “experimental” year of the TLG program to be widely considered a fail.

I am hoping to have an interview with representatives of TLG for the next issue of GEORGIA TODAY to find out how the system looks now; how it has adapted and been adapted to; how the TLG teachers are now prepared and how it has strengthened in its admirable aim to revolutionize the English language knowledge of the people of this tiny Caucasus country.

As always, the monthly CineClub provided another cultural eye-opener. If you haven’t been along to one of their monthly screenings, please do. It is well worth the 5 GEL!

Katie Ruth Davies