The Middle East’s (Eternal) Conundrum: Are We (Really) at a Crossroads?

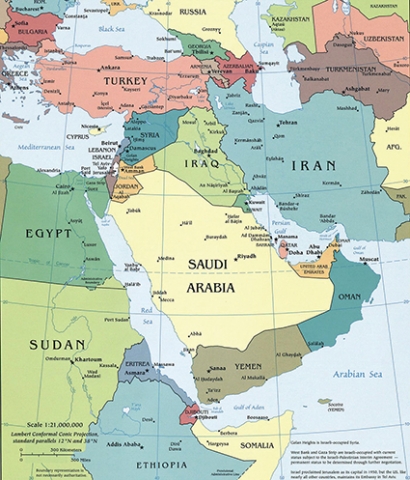

Know Your Neighborhood. And know it as well as you can. This is indeed a most genuine appeal when it comes to discussing what is actually happening in the Middle East, the different lines the region is evolving along and the situation’s effect upon neighboring countries and beyond. Understandably enough, Georgians focus their attention upon partners and forums such as the US, EU or Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), and largely tend to ignore the Middle East and its "suburbs". This, however, is a big mistake, as the latter region is practically boiling over into our own backyard, while Georgia, whether the country likes it or not, belongs to these "suburbs" (i.e. to the wider Middle East, if the reader wishes to cherry-pick nicer expressions).

Insiders: Same Actors, Same Aspirations

The insiders are those states that are always "honorary members" of every club, occupying the front row during developments in the Middle East, and in our view Saudi Arabia, Iran and Turkey may freely qualify as such. And yet we are also firmly of the opinion that the story starts with an opening chapter on Turkey. This should not come as a surprise, since the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the aftermath of the Sykes-Picot Agreement not only led to the empire’s fragmentation but also gave birth to what we formally recognize nowadays as the inner and outer contours (yes, "contours", international and administrative borders being so heavily in flux these days) of the Middle East—a region consumed by a myriad of national, proxy-national, ethnic and ethno-religious conflicts. On top of all this comes the increasing clout of modern Turkey, which, as if reversing the Treaty of Lausanne (the 1923 peace treaty which effectively did away with Turkey as a national state, but was not recognized by the Kemalists), backs up its assertive walk by re-emerging as a regional power. Ongoing operations in Syria and Iraq, the establishment of its largest overseas military base in the Somali capital Mogadishu, and nearly unchallenged control of the waters around Cyprus all predetermine Turkey's heavy influence over Middle Eastern affairs. Yet while Turkey is the only country which unabashedly attempts to shape the future of the region from a position of strength (including through proxies), it is openly colliding with at least three countries which have an interest in the region's future: Russia, Iran, and the US. If read carefully, the Turkish dilemma reflects the problem of being forced into a move one does not want to make, which is sometimes not a symbol of strength, but of weakness. For instance, Turkey is asking for Russia's tacit approval of the Afrin offensive or of the use of military aviation, which reveals Erdogan’s bravado as no more than the subjugation of his actions to someone's will. On the other hand, however, with a predominantly Sunni population and a unique history of direct rule that dates back to Ottoman times, Turkey is relatively well positioned to strike bargains over her interests, and that leverage has very recently being demonstrated during the working-out of a Russian-Turkish modus operandi over control of Northern Syria. Last but not least, Turkey's unwavering ambitions to enter the fray of geoeconomics are evident in its desire to confront Italian and French energy companies in Cypriot waters.

The next country to pay close attention to is definitely Iran, which is experiencing a heyday in the Middle East with an arch of Iranian influence running through Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Qatar. The only country with an overwhelmingly Shia population, Iran fervently competes with the Arab states for regional domination in various ways. By supporting Assad in Syria, for example, Iran is trying to accomplish two goals simultaneously: keeping Iraq as its "backyard" (an unimaginable twist of events when looking back to the Iran-Iraq war in the 1980s), and preserving its access to Lebanon and thus to the Mediterranean. This maverick game does have its own costs, however, since backing Assad's regime pits Iran against Turkey, and its inability to fully match the Turkish military threat forces Iran to rely upon and cooperate with Russia. An even more vivid illustration of the confrontations between Shia and Sunni and Persians and Arabs is Iran’s stand-off with Saudi Arabia in Yemen, where the Saudi-led Sunnis are at loggerheads with the Shiite Houthi rebels supported by Tehran.

Beyond what we nominally consider the Middle East, the latent rivalry between Iran and Turkey is gaining momentum on the region's fringes, with a discreet retrenchment of the latter and the newly reinvigorated revisionism of Russia. The South Caucasus and, more specifically, Azerbaijan, is the arena in which a new kind of future impasse might be emerging. Azerbaijan and Turkey are closely related—ethnically, culturally, linguistically, politically—and Iran’s encroachment in the region relies heavily upon the sizeable Azeri population (nearly 25 million) living in North-western Iran (which the authorities in Tehran also see as a threat in terms of viable secessionist claims). Nonetheless, we are of the opinion that any talk of the balance being tipped in Iran’s favour is premature given the strong military, energy transport and trade links between Turkey and Azerbaijan. It is noteworthy that Turkey recently even suspended the broadcasting of a regular radio program for insulting the President of Azerbaijan and his work. Generally speaking, Ankara is very keen to apply sharp forms of power, and will no doubt continue to do so, for the time being at least. As for Iran, the country is definitely a critical factor which should not be underestimated (e.g. its control over Lebanon and masterminding of Iraqi domestic politics), but Tehran’s influence should equally not be overestimated either (e.g. its inability to fully control Syria).

We have previously made a few references to Saudi Arabia, but the country unquestionably demands closer scrutiny. Far from holding a true hegemony over the running of regional affairs, this state, originally crafted by Britain, presents a unique combination of a long-standing royal dynasty (the Al Saud) and a leading religious family (the Al Shaykh), and the country's governance is the result of a power-sharing arrangement between the two. This vital arrangement can help us to better understand Saudi Arabia’s current stance in the Middle East and beyond. In a nutshell, Saudi regional aspirations are driven by the desire to contain their historical foe, Iran, by curtailing Tehran's direct or indirect influence throughout the aforementioned Iranian arch of influence and by quelling any buds of discontent among Saudi Arabia’s Shia population (a mere fraction of the country's population, but residing in the country’s oil-rich eastern provinces). This rivalry is aggravated not only by Saudi Arabia’s layered and fragile social structure, in which maintaining stability and order necessitates tectonic efforts and flows of money, but also by the need for Saudis to violate their own ideological principles by e.g. acting in tacit concert with Israel through military hardware supplies and intelligence sharing in order to minimize Iranian threats.

Outsiders: The Periphery Does (Not) Matter

The foreign policy pursued by the current US administration has been discussed in detail throughout our various recent articles, and without wanting to repeat some of its characteristics, it is however important to re-emphasize the fact that the current US strategy in the Middle East lacks clarity, and that the US being bogged down in Syria and Iraq certainly boosts Russian “Great Game” in the region. The complexities of US engagement in the region are historical, and lack a linear set of principles when addressing challenges and aligning actions with overlapping interests. These days are no exception, but it still has to be said that the whole relationship system has been turned upside down. To name but a few related "curiosities": the US has to accept Iran when fighting IS in Syria while at the same time confronting Iranian nuclear capabilities; Washington’s support for Kurdish militia (e.g. the YPG) displeases its key NATO ally in the region, Turkey (although the US and Turkey are generally no strangers to disagreement)—a problem compounded by the vague status of the Incirlik air base. As with other international agendas, the Trump administration is facing the same question (an eternal one for major powers): what are US interests? And, most importantly, what price is the US prepared to pay? In defence of the US position, however, it should be stated that developments in the Middle East have their origins not in the Cold War, but are instead predominantly the result of various blood feuds.

Surprisingly to some (which is surprising in itself), Russia’s playing of its Middle Eastern card was deft and timely enough. Alongside hard power (e.g. Russia’s overt military presence in Syria, its use of pro-Assad forces as proxies, the dramatic uptick in arms sale to the MENA region since 2000 and recent Iraqi interest in acquiring the S-400 air defense system), Moscow is actively pursuing a political agenda in the region, and is thereby making a lucky attempt (in the short term, at least) to become an ideological force and paragon (e.g. by hosting its Syrian National Dialogue Congress). This trend has also unintentionally coincided with the US administration’s global withdrawal. Coincidentally, however, is the nagging feeling that Russian gains are only temporary, since developments in the Middle East are for domestic consumption only, and when it comes to a domestic agenda, many critical things need to be watched closely and indeed feared in terms of the sustainability of Russia's political and economic fundamentals.

Israel also deserves special mention in the Middle Eastern context, but this should be a matter for separate and more extensive discussion.

All This Matters To Us

Several undeniable and critical features are easily detectable in Middle Eastern developments (and indeed beyond): national states raising the stakes by projecting power across their national borders and tailoring their interests by regionalizing them; and the mightier and more ambitious a state is, the wider its regional dimensions become. Perhaps this is also characteristic of the rapidly changing world order, which has become less constrained by national frameworks and strongly tilts towards extending coverage over entire regions at a stroke. And besides, the experiment of creating a "Mesopotamian liberal democracy" has also failed.

Clearly, the risks the region presents put us, Georgia, on high alert—not only militarily (which, if asked, is of lesser concern) but also in terms of the challenge of preserving national and social cohesion, avoiding unrest and disruption and preventing friction between different communities. This is of course a topic that merits wider discussion and lies beyond the scope of this article, but a few key thoughts came to our mind at this point. Firstly, the importance of mechanisms for properly co-ordinated intelligence sharing with our allies and partners. This would be possible by building up truly formidable intelligence services at our end, whose work would exclusively focus upon national security concerns (and nothing else), staffed with real professionals and, quite frankly, patriots (alas, we are forgetting the word). Secondly, that of mitigating (if not eliminating) potential sources of ethnic or religious discontent within the country by dynamically incorporating such concerns into a truly national discussion. And lastly, we should seriously attempt to become a regional centre for dialogue and peace by turning Georgia into a convenient forum (a "Vienna of the Caucasus"?) in which conflicting parties can meet and hold discussions. The need to rise to these and countless other challenges requires us to “think big” and to think boldly.

By Victor Kipiani