Will We Ever Get There?

OP-ED

Ihave written before that Georgia is a land of poetry. Almost every Georgian is a poet. Poetry is in our blood and verve. The word ‘poetic’ would be the fittest epithet to describe Georgia as a nation. One can hardly imagine a Georgian who has not written at least one verse in his or her lifetime. Some of those poetically-minded people become qualified poets and earn fame and make money by effectively marketing themselves. Some remain in the shadows forever. Those who are luckier successfully feed their poesy to the public, leaving a noticeable trace in their hearts and minds. Some of the talents even manage to get the word beyond the boundaries of their motherland. They manage to do so because they have managerial talent in addition to their poetic gift. Some of the greatest poets of Georgia have never become known to the world because nobody has bothered to translate them from the Georgian language, spoken by only several million people, into English, used by most of Mankind. Nobody has tried to promote them commensurately with the extent and degree of their poetic aptitude.

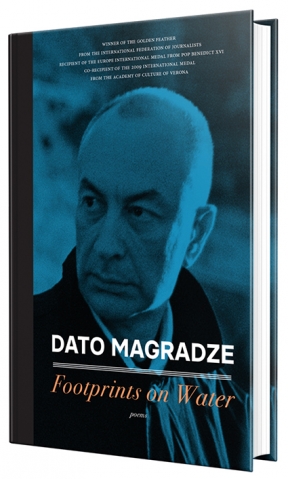

Georgia truly has some world-level poets who will never be known to humanity in the way and dosage they deserve to be. Among the lucky ones is poet Dato Magradze. As a Georgian, I welcome his success unconditionally (and sober-mindedly too for that matter). His poetry has been translated into several languages and recognized by a number of nations. Last Monday, September 24, was marked the continuation of his flourishing poetic career thanks to his book of poesy, titled Footprints on Water. The edition marked the propitious debut of the lucky Georgian in the United States, a man who has already earned international acclaim, including: the Europe International Medal from Pope Benedict XVI for his collection ‘Salve’; the Golden Feather from the International Federation of Journalists in 2005 for his text of the Georgian national anthem; and an international medal from the Academy of Culture of Verona for his work promoting free speech.

Obviously, his own nation is also celebrating its poet son and his works because he has taken Georgia’s name and fame beyond its modest limits. I can’t be happier than this because my countryman has made it and will go even further as soon as another opportunity pops up. And I am more than certain that the chance will come again, knowing how professional Magradze sounds in his poetry and how adamant he happens to be in his determination to have translated his creative output into other tongues and to get his poetic word across to peoples other than Georgian.

I only have one straightforward and unassuming question to ask: in which particular case, out of the given two, would Georgia be a bigger winner – if Magradze energetically promoted his own poetry in the international arena or if he dedicated his talent and capacity with the same vigor to the cause of upholding the genuine sovereigns of Georgia’s poetic thought and flair like Galaktion Tabidze and Vazha Pshavela, or others of that enormity, especially if we already have the translation of some of their works ready to be presented to the world for appreciation, like the recent outstanding translation of Galaktion Tabidze by professor Innes Merabishvili. In other words, should the world know Georgia more via Poet Dato Magradze or Poet Galaktion Tabidze? I mean, what would make the nation stronger?

I understand that men value their own skins more than those of others, but we are now talking about the chance to have the world think of Georgia the way this nation needs and deserves. Dato Magradze definitely has my consideration but I can’t escape the burning query of my lifetime – what is it that our little darling Sakartvelo needs most in order for it to swing its intellectual power to the fullest possible extent? Well, poetry is just a drop in a bucket – I just came across the issue and trivially dwelt upon it. What hurts my soul and pricks my conscience is not that! It is my doubt as to whether this nation remembers or not that ‘first things first’ really matters and precisely answers the most commonplace rhetorical question in Georgia – ‘will we ever make it?’

By Nugzar B. Ruhadze