Georgia’s Democracy: From Guns to Dreams & Roses. What’s Next?

The results of the first round of Georgia’s 2018 presidential elections are being discussed everywhere. Street corner gatherings, the ‘birzhas’, are seething with excitement. While quite emotional at times, the level of typical ‘birzha’ exchanges may surprise observers. For one thing, positions are often better grounded in facts than those presented by pundits, TV talk show participants, and parliamentarians.

CHAPTER I: “BIRZHA” POLITICS

We both live in the Saburtalo district of Tbilisi – a dense agglomeration of Soviet blocks of flats dating back to 1970s. Ugly on the outside, but quite cozy on the inside («страшные снаружи, добрые внутри», as a Soviet song from the same period goes). Two days after the elections, we decided to step out of our cozy apartments into the thick of the neighborhood’s street-level democracy.

Saburtalo’s political stance has evolved quite considerably since 2012. In that year’s parliamentary elections, 70% of the Saburtalo vote went to the Georgian Dream (GD) alliance, leaving the ruling United National Movement (UNM) with only 25%. In the 2013 presidential elections, GD’s Giorgi Margvelashvili – the new ruling party’s candidate – crushed his UNM opponent: 66% to less than 18%. GD’s advantage over the UNM significantly eroded in the 2016 parliamentary elections: 49% to 27%. Finally, the results of last week’s presidential elections show that Saburtalo is once again a toss-up district: GD-sponsored presidential nominee Salome Zurabishvili (37.5%) is neck-and-neck with UNM’s Grigol Vashadze (30%), assuming he gets the support of those who voted for his former UNM colleague and Ministry of Foreign Affairs boss David Bakradze (6.8%).

Our neighbors come from all walks of life, and the ‘birzhas’ we attended were quite representative of the district’s mixed demographics and political views. That said, there was one thing everybody seemed to agree on: Georgia is making progress as a democracy, enhancing ordinary people’s confidence that they are the ultimate power holders in society. Both sides also shared a concern: the opposition candidate’s victory may destabilize Georgia’s fragile political situation, unleashing pro- and anti-government street action and, potentially, violence.

CHAPTER II: DOMINANT PARTY POLITICS

While civil war, gun violence and political assassinations of the 1990s are all but forgotten, Georgia’s democracy is still a work-in-progress. The country’s political culture is far from passive and submissive, but, so far we have been living under an elected single-party dictatorship, not a vibrant democracy. Time after time, the Georgian people vote for the ruling party, allowing it to achieve a constitutional super-majority in the parliament and rule over all Georgian municipalities. Opposition forces are visible only in Tbilisi, but even here they are hopelessly divided. And then, after 8-10 years of submission to a one-party rule, come political convulsions and revolutions... That's not anyone’s ideal of democracy.

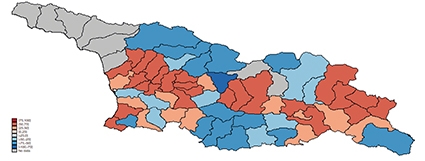

Figure 1. Election results for party list representation in parliamentary elections (2008, 2012, and 2016) and local elections of 2017. A red country turning blue in less than 10 years.

Note:

I Parliamentary elections, 2008

II Parliamentary elections, 2012

III Parliamentary elections, 2016

IV Local elections, 2017

CHAPTER III: MULTI-PARTY DEMOCRACY?

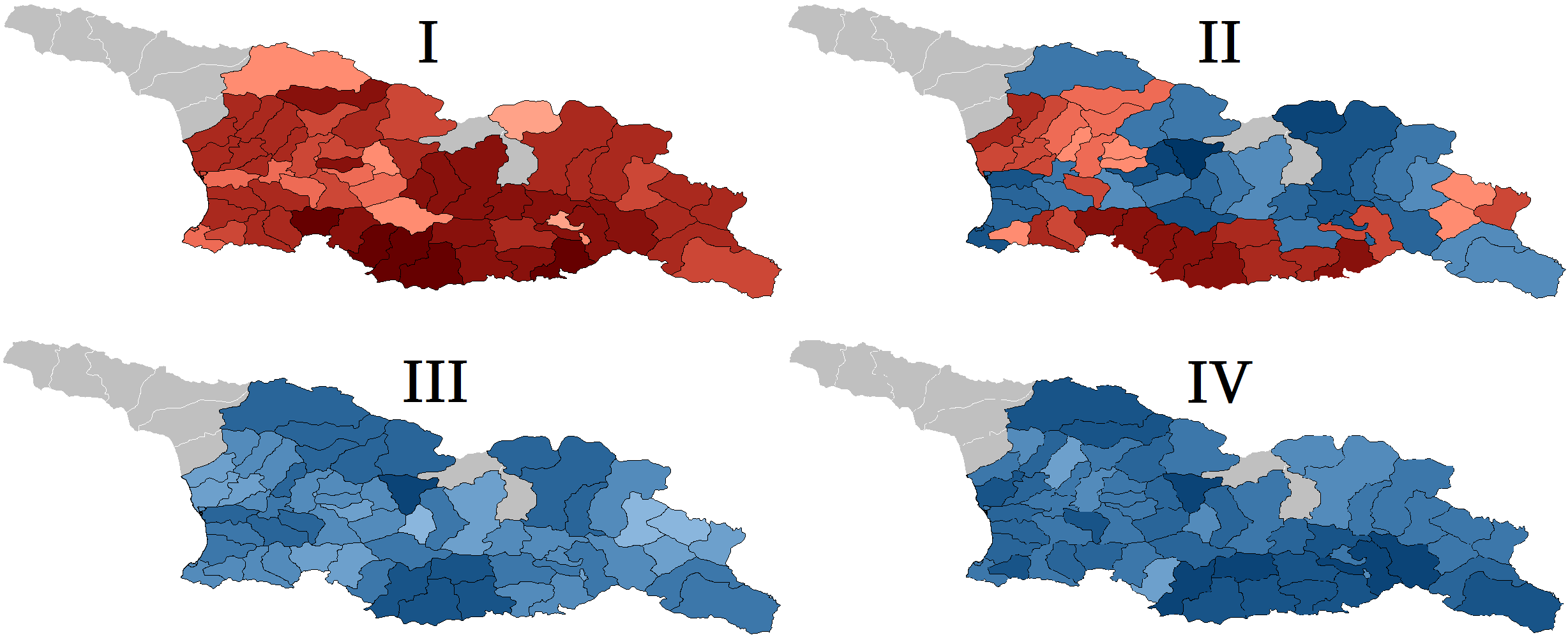

The 2018 presidential elections add color to Georgia’s monochromatic political map. The country as a whole and each municipality (with the exception of Sachkhere, Bidzina Ivanishvili’s home turf) are now divided among two-three parties.

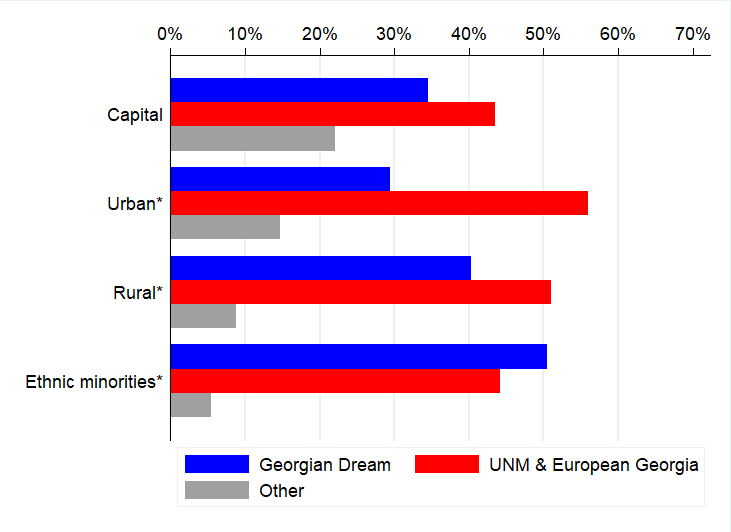

As in the past, the ruling party (GD) does relatively better in rural and ethnic-minority municipalities, but is far from winning them all.

The optimists among us may regard such a high level of political contestation as a sign of a genuine multi-party democracy finally striking root. However, this holds only if parties on all sides of the political divide recognize each other’s right to exist and the electoral system is re-engineered accordingly: to represent Georgia’s cultural and political diversity rather than allowing one faction to dominate over the other.

So far, there has been little indication that the warring parties are ready for compromise. The rhetoric and actions we’ve seen in this election were of the single-party domination variety: mud-slinging, abuse of administrative resources, and electoral bribery. Georgia’s ‘corner boys’ may feel somewhat empowered but our politicians are still thinking in zero-some-terms, trying to maximize their private gains – and not much else, as reflected in recent statements issued by leading presidential candidates: “These are not elections between two parties, this is about choosing between two Georgias!” (Zurabishvili); “[The second tour] will be all minus one!” (Grigol Vashadze).

CHAPTER IV: TIME FOR EXTRAORDINARY DECISIONS!

In extraordinary times, extraordinary decisions are required. In early 1990s, as South Africa was preparing to end the Apartheid, the warring parties agreed to form a Government of National Unity in order to steer the nation’s painful transition to a more inclusive future.

The South Africans managed to strike a political deal despite sharp racial and class divisions, as well as a long history of mutual hatred, colonial domination, discrimination and rebellion. Georgia may be culturally and economically divided into its liberal and conservative halves, yet the main driver of Georgia’s all-or-nothing politics is not a clash of values or ideology, but the big egos of its alpha-male businessmen and politicians.

Members of Georgia’s political elites have to realize that they will not be able to eliminate each other and have much more to gain by concluding a pact of mutual recognition. An extraordinary precedent in Georgia’s modern history, such a pact could take the form of a broad political agreement to reform Georgia’s electoral law and hold early parliamentary elections.

Indeed, by abolishing single-member districts (which are the root cause of parliamentary super-majorities) and introducing voting on nation-wide party lists, Georgia would take a major step towards a healthier political situation in which major choices are rigorously discussed and contested. If held in the new format, parliamentary elections would most probably produce the first truly coalitional government, one based on compromise rather than outright domination.

* * *

We did not bring up our vision of an internal peace treaty among Georgia’s political factions at any of the ‘birzhas’ we attended. Having experienced guns, rose revolutions and Georgian dreams, the Georgian people have learned to be skeptical. Still, this week’s Tbilinomics Tamada toast is a very traditional one: to peace – not only with our enemies, but within our own nation.

About the author: David Aprasidze is a political scientist working on political transformation and democratization issues. He is a professor at Ilia State University and a senior associate with Tbilinomics.

By David Aprasidze