Georgia’s Medical Education: A Party Soon Coming to an End?

The headline in Haaretz, Israel’s leading newspaper, sounded alarming:

“Thousands of Doctors Study Abroad – and They're Threatening Israeli Health Care”

The subtitle provided a bit more background: “Israelis who have studied in places like Armenia and Moldova aren’t getting enough experience with patients and the director of the Health Ministry is losing sleep over it.”

The fact that thousands of Israelis are pursuing medical education in low quality schools outside Israel is nothing new. Back in the 1980s, a key destination for wannabe Israeli doctors was communist Romania. Nicolae Ceausescu was happy to export anything, including university degrees and Jews (an “exit visa” for a Jewish family was valued at $10,000, willingly paid by the Israeli government at the time).

With the fall of communism, Romania lost its privileged status as an affordable medical education “hub” and Israelis started exploring education options (a little bit) further to the east. As reported by Haaretz, a particular school in Kishinev, Moldova, currently has about 1,300 Israeli medical students and 200 dentists enrolled. According to Prof. Shaul Yatziv, the person in charge of licensing medical professionals in Israel, “it’s simply impossible to provide satisfactory clinical experience for 2,000-plus students, Israelis and foreigners, in one hospital. … In Israel, a comparable number of students are trained in 20 different hospitals.”

But the low quality of clinical training (or its complete absence), is not the only concern with the cheaper education providers. With no strong public control in place, there is little to prevent “students” and “universities” from simply exchanging (a little bit of) money for diplomas. This is an excellent business given that all parties to such transactions hardly break a sweat. And we’re not talking about a hypothetical possibility – in November 2018, Israeli police arrested 40 doctors, residents, and pharmacists who were able to obtain diplomas from Armenian “schools” without spending almost any time in Armenia.

IS GEORGIA THE NEXT ARMENIA?

Bumping into an Israeli guy studying medicine in Tbilisi came as something of a surprise. And yet, here he was, Ameer Falah, a 3rd year student at the Tbilisi Medical Academy, waiting on my table at Sivan and Shalva’s Israeli Hummusbar.

Ameer, 28, came to Georgia in March 2016, having decided to reinvent his life after eight years in Israel’s restaurant sector. “My older brother, Ahmad, studied medicine in Italy,” he tells us. “He convinced me to follow in his footsteps, and promised to help, both financially and academically.”

As Ameer tells when we sit down for an interview, he may be the only Israeli at Tbilisi Medical Academy, a relatively small private school in Avlabari. Foreigners constitute about 50-60% of TMA’s 800 students, and of those, the majority are from India.

Ameer is happy with the deal he’s getting. He pays $5,000 in annual tuition fees (“now students have to pay $6,000”) and spends another $800-900 per month on rent and living expenses. The university takes good care of all his needs, and the city is safe and fun to live in. He is lucky to study in a very small group of seven students. Five Indians and a Georgian guy, in addition to himself. Most groups include 10-12 students.

Ameer’s three years at TMA covered basic theory, taught from standard international textbooks used at any university around the world. Practically all theory lecturers at TMA are young Georgian women (“Men don’t work here,” he says. A friend once sent him a picture of Mother of Georgia and a guy - Father of Georgia? - lying on his back next to her. Ameer thought it provided a good summary of the city’s spirit.) The teachers are doing a good job. But, even if something is not clear, one can always watch the “World’s Most Popular Medical Lectures” by Dr. Najeeb, a major online resource for medical university students worldwide. (Having watched just one lecture by Dr. Najeeb, we started wondering whether it would not make sense to have him teach the entire world population of medical students).

While Ameer is a happy man, his account contrasts with those of other students we’ve interviewed, especially those in the more advanced stages of their studies. For example, M., a 6th year Indian student at the Tbilisi State Medical Academy (one of Georgia’s most prestigious medical schools) describes the inefficiency of waiting outside the teacher’s office for a chance to observe an examination of an occasional patient. There are 20 students in the line; the patients are few and far between; and only three students are allowed in. To add insult to injury, a lot of time is wasted on translating Georgian language conversations (which few foreign students are able to understand) to English. Likewise, M. sees little benefit in doing nightshifts at a hospital where he does not get to do or learn anything new. Another issue is the great variation in his teachers’ motivation and attitude. Some are great, but many simply don’t care.

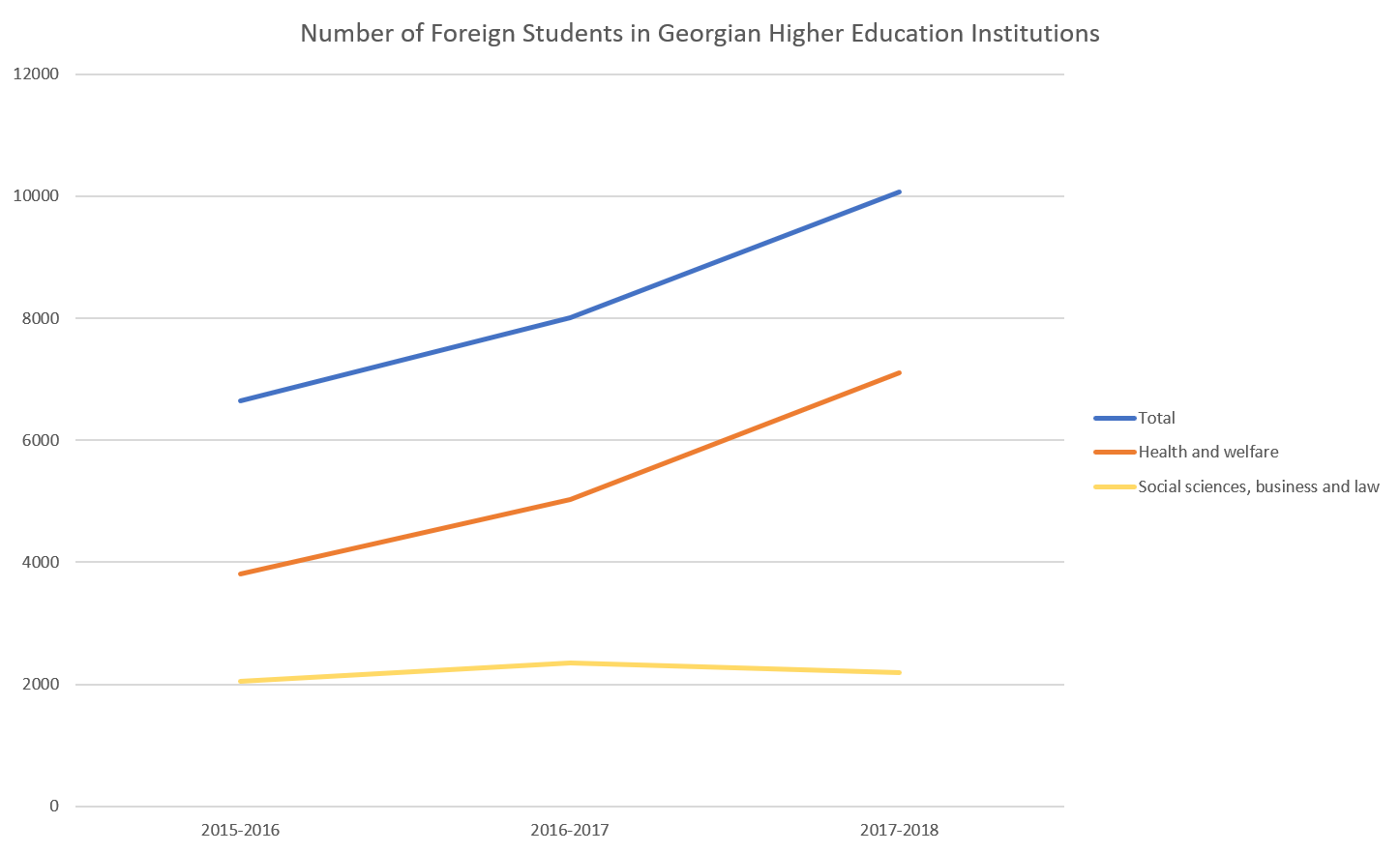

Ameer and M. are just two of more than 7,000 foreigners who have studied in Georgia’s medical schools in 2017-2018 – a staggering figure for a country of Georgia’s size! Mind you, the foreign student population in Georgian medical schools almost tripled in just three years (since 2015-2016). At this rate of expansion, Georgia’s hospitals have long exhausted their capacity to provide meaningful clinical experience to thousands of foreign and domestic students. There are simply not enough hospitals (or patients) to supply the students’ clinical training needs.

À LA BUSINESS COMME À LA BUSINESS

Medical education is serious business and a major source of foreign currency earnings for Georgia. Assuming an average tuition rate of $6,000 (programs preparing foreign students for the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) cost closer to $10,000 per year), Georgia’s medical schools generate more than $40mln in annual revenue. Moreover, as assessed in “Brief Migration Profile: Foreign Students in Georgia” tuition constitutes only 39% of foreign students’ total expenditures, which includes rent, food, transportation, and utilities. Applying this ratio, we estimate that, in 2017-18, foreign medical students have spent over $100 million, accounting for close to 0.7% of Georgia’s GDP in 2017.

Because it is serious business, Georgia’s medical education sector is treading the Armenian (and Moldovan) path. Georgia’s National Agency for Education Quality Enhancement (EQE) is doing what it can to protect the sector’s integrity, but the crude authorization and accreditation tools at its disposal do not allow it to do enough. While Israel may be too elitist when it comes to selecting medical students, Georgia’s 24 medical schools do not even bother administering entrance exams. The ease of getting in (also thanks to special arrangements with Indian recruitment agencies) is, in fact, their major selling point.

Georgia does require foreign students to demonstrate English language proficiency. Few Georgian schools, however, make an admission decision conditional on official certification, such as TOEFL. Tbilisi Medical Academy, for example, promises to accept any applicant who can “demonstrate fluency to the University special comity (can be done through the Skype call)” [sic!]

Judging by how English language requirements are spelled on TMA’s official website, we doubt its “special comity” has the capacity to assess the candidates’ English language proficiency. And given its business interests, it may not have the motivation to do so, either.

THE PARTY COMING TO AN END?

The situation in Georgia’s medical education sector may change very soon. In 2018, the EQE joined an exclusive club of accreditation agencies recognized by the World Federation of Medical Education (WFME). According to Lasha Margishvili, head of EQE’s higher education department, EQE has already revised its “sector benchmarks” (e.g. concerning labs and own clinical facilities), as well as accreditation standards and procedures. These will become mandatory as of 2023.

There are several implications for EQE itself, Georgia’s medical schools and their students.

First, WFME recognition raises the quality bar for the authorization of medical schools and program accreditation.

Second, in contrast to the current situation, only students of WFME-accredited schools will be allowed to take the sought-after US Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE).

Third, authorization/accreditation committees will include international experts hired by EQQ (relevant costs will be charged to medical schools seeking authorization/accreditation).

Fourth, all authorization/accreditation decisions will be made by an independent council (separate from EQE), whose members will be appointed by Georgia’s Prime Minister. This council will consist of 16 members, including representatives of students, NGOs, academia, and the medical profession. A 75% majority will be required for approval.

* * *

At least on paper, these new regulations could have the potential to prevent Georgia’s medical education from following the Armenian scenario. If all goes well, the sector is likely to see a greater investment in the quality of faculty, lab equipment and clinical facilities, on the one hand, and a gradual process of consolidation, on the other. The latter is essential because Georgia does not have the capacity to train 8 or 10 thousand medical students, and it can ill afford losing its reputation given its ambitions to join the European family of nations.

About the authors: Eric Livny and Rezo Surguladze are president and research economist with Tbilinomics Policy Advisors. Vato Surguladze is dean of Caucasus University’s School of Medicine and Healthcare Management.

By Eric Livny, Rezo Surguladze, and Vato Surguladze

Image: A group of 6 medical students undergoing clinical training at Israel's Tel Hashomer Hospital. In Georgia, clinical training is delivered to groups of up to 20 students.