What Do We Need So Many (Standard) Exams For?

BLOG

A professional violinist by training, Keti Kipshidze is probably one of the best guitar teachers in Tbilisi. Having graduated from Erik Arakelov’s class at the Tbilisi Conservatorium in 1994, she auditioned for the Tbilisi Opera and Jansug Kakhidze’s Symphony Orchestra, but failed to get a job. In 1994, one could still hear Kalashnikovs on the streets of Tbilisi. The muses went silent.

Many of Keti’s classmates left the country. Keti stayed, and in 1998, following the advice of Tengiz Gamitadze, a great musician and her guitar teacher since age 13, she took a few teaching classes and embarked on a new career, that of a private guitar teacher. Keti’s jovial, glass-half-full personality and musical talent (she sings, too!) were her key to success. Over the course of more than 20 years, she has taught and inspired hundreds of young people and become a great friend in the process.

When we met in early February 2019, Keti was full of excitement. She has never been short on demand but lately demand has been truly exceptional. As many as eight interested students called, repeating the same story over and over again. “The government has just announced that there will be no more school leaving exams. We will now have more time for things we really care about, such as music”.

I ask Keti what she thinks about the government’s decision to abolish the school graduation exams. “Our talented-but-lazy kids probably do need deadlines and exams”, she responds, “but there should also be much more flexibility for them to choose what to study. Why should we force everybody into the same mold?” And there comes a classical Keti Kipshidze joke: “You know, I am still looking for an opportunity to use any of the school math that was hammered into me, all this tangent-cotangent stuff”.

MUCH ADO ABOUT WHAT?

The sudden surge in demand for Keti Kipshidze’s guitar lessons followed a government announcement that nationally-administered university admission tests (“Uniform National Exam”) – a key symbol of Saakashvili era reforms – will from now on include only three compulsory subjects: Georgian language and literature, foreign language, and either math (for those planning to acquire a technical qualification) or history (for those interested in social science and humanities). The general ability test, which used to have the largest weight in the Uniform Exam, will no longer be mandatory, however universities will have the right to require it. And, from 2020 onwards, students will no longer be required to take school leaving exams in order to get their General Education certificates. 11th graders will not be examined from 2019; 12th graders will be exempt starting 2020.

This announcement was explained and enthusiastically endorsed by supporters of the Georgian Dream side of the political spectrum as a potential panacea for all the ills of the Georgian education system. Kakha Kaladze noted that “education is a constitutional right, not an obligation”. In other words, if somebody needs exam results in order to study, it is his or her responsibility. Minister Batiashvili explained that this change is only one element of a broader education sector reform seeking to empower Georgian schools, give them more autonomy and strengthen their incentives to educate as opposed to prepping students for standardized tests. By changing the way students’ performance is assessed, the new system will also drastically reduce parental expenses on useless tutoring, while giving kids more time to invest in music and other types of actual learning. Hallelujah!

Many Georgians speaking out in social networks do not share in this optimism. Some are scared of Shevardnadze-era corruption making a victorious comeback. Students and educators I spoke to raised more serious contra arguments. Nino Sarishvili, one of my best students at ISET, thought that the specter of rigorous school graduation exams motivated many of her academically weaker classmates to go into professional training as opposed to continuing to grades 10-12. “With no exams, they would have stayed in the general education system – a huge waste of time as far as such students are concerned.”

A very strong argument was provided by Iwa Mindeli and Natia Andghuladze, senior education experts previously associated with NAEC, the government agency in charge of running standardized tests. According to their data, the rural-urban gap in performance on standardized tests is smallest (8.1 points on an 80-point scale) in the general ability test, and largest (22 points on a 90-point scale) in the foreign language. By abolishing the general ability test while maintaining the current system of allocating university grants, the government will further skew the distribution of such grants (and university education) in favor of Tbilisi and large urban centers. They would not be opposed to the abolition of standardized tests, provided the government abandons the current – “money follows students” (and nothing else) – approach to financing university education.

A REFORM LONG OVERDUE!

Modern public schools, as we all know them, are a relatively recent invention. 19th century Europe needed literate industrial workers and patriotic soldiers. Therefore, Europe’s public schools (as opposed to public-in-name-but-private-in-essence Eton and Westminster) were designed and financed for this very purpose: delivering standard (“French”, British” or “Russian”) mass education for assembly line workers and soldiers. Public school curricula of the time did not venture beyond basic literacy in a “national” language, basic numerical skills, and national-religious mythology and prayers. The standard school pedagogy included top-down lecturing, learning by rote, and harsh physical punishment for the lazy and undisciplined – excellent preparation for the future ‘cannon fodder’ and industrial proletariat.

Fast forward to the 21st century. Gone are blatant gender and racial discrimination, illiteracy and harsh physical punishments, but relatively little has fundamentally changed in many, if not most, national education systems around the world. Modern-day Etons and Westminsters still exist almost everywhere except a handful of Nordic countries. With “Quality”, “British”, “American” or a similar geographic denomination in their title, these cool and innovative institutions employ modern technology and offer plenty of individual choice. Moreover, they now serve a larger share of the population – not only upper-class boys, but also girls. Unfortunately, however, these schools are also the very expression of social inequality and the main means of its conservation.

Public schools, on the other hand, still use the same time-tested top-down methods of instruction and serve the same purpose: delivering basic literacy, numeracy and patriotism for the rest of the society – urban and rural poor. Their education ‘standards’ are defined and enforced through a ‘national curriculum’ and nationally-administered exams. These standards and exams allow very little autonomy for schools or teachers. Consequently, there is almost no flexibility or choice for students in the public education system: everybody must take the same core subjects and pass the same national exams.

Of course, standard curricula and exams are not the worst thing that can happen to an education system. It is much worse for a society to have schools that teach almost nothing at all, schools with no heating, and teachers who are paid almost nothing. And given the sorrowful state of Georgia’s schools and universities until well into the 2000s, investment in basic infrastructure and standardization were hailed as major achievements in the country’s post-Rose Revolution realities. Moreover, introduced in 2005, standard national tests had the added advantage of helping eradicate corruption and creating a meritocratic mechanism to allocate public funds to students, and students to universities. These tests, wrote Transparency International in 2005, were “a watershed in Georgia’s history… They showed that it is possible to conduct a fair and impartial competition throughout the country.”

Nationally-administered university admission tests are a key symbol of Georgia’s Rose Revolution. Like many other Saakashvili-era reforms, they provided a civilized façade to an otherwise outdated, underfinanced and dysfunctional system. While helping eliminate corruption, standardized tests did not address any of the fundamental problems in Georgia’s education system. Gone is corruption, but where is the quality? Where are the educators that can prepare our sons and daughters for 21st century occupations? Certainly not in Georgia’s public schools.

And just as the standardized test and exams did not prove to be a “watershed event” in Georgia’s modern history, their abolition, in and of itself, is not going to be a major game changer either. It is definitely a step in the right direction, giving schools and teachers greater freedom to create the new and different. But it will not endow them with the professional abilities and resources to do so. For now, Georgia’s one-size-fits-all education system is geared towards producing barely literate “managers” (modern day assembly line workers) and patriotic soldiers. When thousands of “managers” hit the labor market, the result is not a well-managed economy, but mass unemployment, frustration and emigration.

To truly redeem the vast majority of Georgia's youth of their underprivileged childhood, Georgia has to move beyond simple “standard” solutions and invest – quite heavily! – in the quality of its public schools and its teachers. Achieving this feat will require a long-term effort to be sustained over a generation.

About the author:

Eric Livny is Founder and President at Tbilinomics Policy Advisors. In 2007-2018, he served as President with the International School of Economics at Tbilisi State University (ISET) and ISET Policy Institute. His current advisees include the Caucasus University and the Finnish International School project.

By Eric Livny

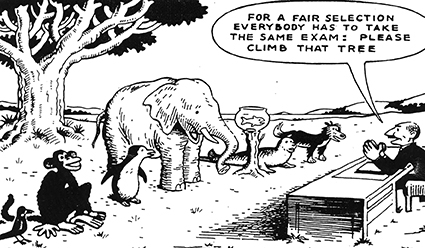

Main image: “Everybody is a genius. But if you judge a fish by its ability to climb a tree, it will live its whole life believing that it is stupid” (a saying, often attributed to Albert Einstein)