In Big Men Georgians Trust!

While we don’t trust each other and people who are supposed to represent us (political parties and NGOs are the least trusted Georgian institutions!), we do seem to believe in strong authority embodied in Georgia’s Big Men, our Church, the military and police. And, as long as we fail to get our act together, we will have no choice but continue to expect favors from the next Big Man, hoping that he will be a little bit better than his predecessor (or at least less crazy).

* * *

Zurab Zhvania, a founding father of modern Georgia and a prominent leader of the first generation of Georgian reformers, was once asked whether Georgia had any assets it could rely on. “Our democracy,” was Zhvania’s instinctive response. By the same token, the politician and public figure Levan Berdzenishvili later joked that God endowed Azerbaijanis with oil, Armenians with a large and influential Diaspora, whereas Georgians have nothing but their democracy.

While Georgians have a lot of appreciation for civic freedoms and democracy, their governance is not particularly democratic. Georgia seems to be forever “lurching towards democracy”, to rephrase the title of a late 1990s book. Our situation reminds me of Diaspora Jews who for 2000 years have been praying for the “Next year in Jerusalem”. “Next year in (democratic) Europe” may have acquired a very similar semi-religious meaning in Georgia’s contemporary political discourse: a lofty but elusive ideal.

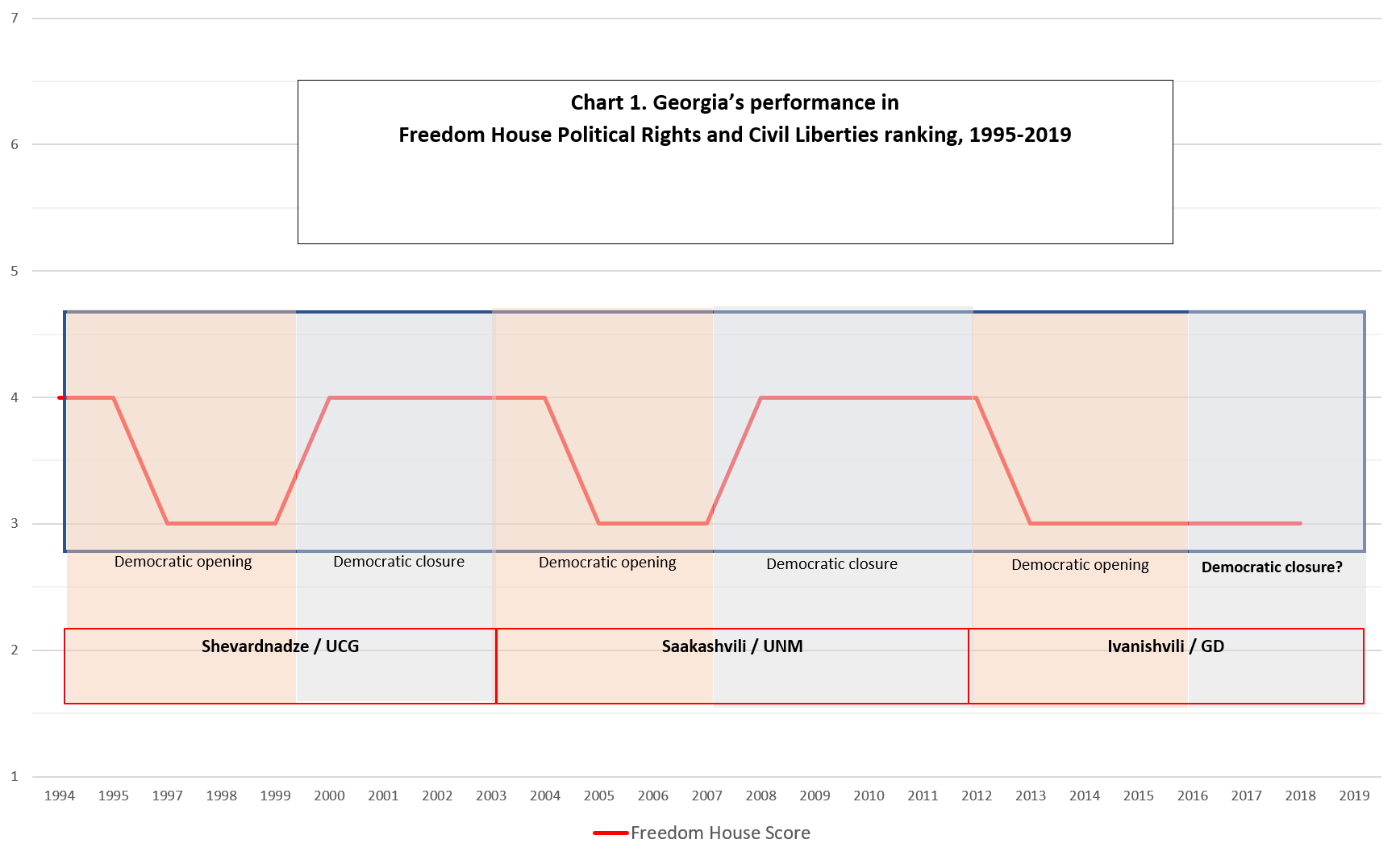

An annual ranking is based on data from the previous year, i.e. the 2019 ranking is based on 2018 data.

Indeed, since acquiring independence in the early 1990s, Georgia has not been able to escape the twilight zone between democracy and autocracy. According to the most recent assessment by Freedom House, Georgia is classified “partly-free”, having lost only one point (on a scale of 100) compared to the previous year. Similarly, Georgia is considered a “hybrid regime” (between “flawed democracy” and “authoritarian regime”) by the Economic Intelligence Unit (EIU) of The Economist. In 2018, Georgia’s score in EIU’s Democracy Index dropped from 5.93 to 5.5 (on a 10-point scale), the steepest decline in the region, according to Georgia Today.

Georgia’s ranking in Freedom House Index since 1995 (see chart) reveals an interesting regularity:

• From the moment Georgia adopted its first constitution and started looking like a state, its democracy score has fluctuated within the margins set for “partly free” nations (between 2.5 and 5.0 on a 1-7 scale, with 1 representing the ideal of democracy and civil liberties).

• Georgia’s score improved to 3 in periods in which the ruling parties were consolidating their power. We refer to these episodes as periods of democratic opening.

• Conversely, Georgia’s score went a notch down, to 4, when the ruling parties were desperately trying to hold on to power in the face of mounting opposition. Two such downturns (or democratic closures in our terminology) coincided with the second terms of Messrs. Shevardnadze (2000-2003) and Saakashvili (2008-2012). The first signs of another downturn have become visible since Mr. Ivanishvili official return to power in 2018.

These ups and downs remind us that after 25 year of independence we still have a long way to go as far as our democratic governance is concerned. An even bigger question for the vast majority of Georgians is whether the country’s democratic advancement can bring tangible improvements in the lives of ordinary citizens. In the end, as a popular joke of the first years after the Rose Revolution goes, – “can we eat democracy?”

BAKERS AND POLITICIANS

When it comes to professionalism, Georgians love to recite the 18th century poet David Guramishvili whose famous “bread must be baked by the baker” is invoked whenever we are not happy with the quality of services or goods we are offered.

But, as we know from basic economic theory, to produce good bread (and sell it at a reasonable price), bakers must operate in a competitive environment. And what is true for bakers is equally true for politicians. A lack of perceived competition is likely to make even the greatest among them insensitive to popular demands or new ideas. Whether she said so or not, Marie Antoinette’s “let them eat cake” can serve as an illustration of such extreme insensitivity.

Democracy’s key virtues, at least in theory, are public debate and competition, but nations can be democratic in form while maintaining very different degrees of political competition. Some democracies have been for very long stretches of their history ruled by a single party (Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party, Israel’s MAPAI). Others have had periods of too much political competition, resulting in very frequent elections and government changes. The French Fourth Republic (1946-1958) is a classic example of the latter: during its 12-year history it was ruled by 21 different administrations.

GEORGIA’S BIG MEN AND DEMOCRACY

Where is Georgia’s place between these two extremes of too much vs. too little competition?

Whenever we analyze Georgia’s democracy, we tend to focus on excessive concentration of political power in Tbilisi. But, let us not forget that politics (democratic or not) originate at the grassroots, in Georgia’s ordinary settlements – villages and small municipalities. And what we find at the grassroots of Georgia’s politics is not public debate or competition, but The Big Man („დიდი კაცი“ in Georgian).

The Big Man takes care of all issues faced by local businesses and fellow citizens; He (very seldom a “she”) is also the first person anyone outside will try to approach when dealing with the community. Salience in local politics and a strong clientele base make The Big Man an attractive target for national actors who would gladly co-opt Him with little regard for shared values or political vision.

Of course, The Georgian Big Man has many rivals and challengers, as all big men do. Lacking in authority and resources, his rivals are waiting for an opportunity to challenge and replace Him. However, they do not seek to challenge and change the system.

The Georgian Big Man phenomenon is apparently rooted in the chronic failure of collective action at the level of Georgia’s local communities. More than 50% of Georgian respondents in CRRC’s 2017 Caucasus Barometer survey claimed to have no or little trust in fellow citizens, as opposed to less than 20% who reported some or full trust. Statistics aside, we are reminded of our failure to cooperate and contribute to a common pool of resources every time we enter our dirty and poorly lighted blocks of flats and have to drop a 10 tetri coin in the elevator’s slot machine.

While we don’t trust each other and people who are supposed to represent us (political parties and NGOs are the least trusted Georgian institutions!), we do seem to believe in strong authority embodied in Georgia’s Big Men, our church, the military and police. And as long as we fail to get our act together and cooperate, we will have no choice but to continue to expect favors from the next Big Man, hoping that he will be a little bit better than his predecessor (or at least less crazy).

* * *

A key challenge of Georgia’s “partly free” politics is the fact that there are “Big Men” everywhere – in villages and small communities, businesses and NGOs, schools, universities, political parties, and so on and so forth, all the way up. However, the “partly free” Georgian nation is not fated to be dominated by crazy-and-brutal or wise-and-goodhearted Big Men. It is time for us to get organized and collectively design better laws and institutions that govern our life: elections and party financing, taxes and trade, industry, agriculture, education, and everything else.

Next year in Jerusalem!

By David Aprasidze

About the author:

David Aprasidze is a political scientist working on political transformation and democratization issues. He is a professor at Ilia State University and a senior associate with Tbilinomics.