Education for the 21st Century: Broad, Deep or Flexible?

BLOG

My lecture on the future of education in the 21st century was intended for a small number of Caucasus University students and faculty. Since I don’t really know how school education is going to look like in 20 or 30 years, my plan was to have an open-ended “Socratic discussion”, with me and other participants seated in a U-shape or a circle. Yet, the classroom was arranged in a very traditional way. Behind me was a white board; facing me were neat rows of desks. That’s how the first modern schools looked like in the second half of the 19th century. And that’s how most humans still teach and are taught today.

Yet, the way we learn is related to the type of knowledge or skills we are trying to acquire. For example, learning to become a farmer or a master craftsman in the 17th century was very different from learning to become a patriotic soldier in a 19th century nation state, or an assembly line worker in a factory powered by Watt’s steam engine.

A BIT OF HISTORY

In 1689, the year of England’s Glorious Revolution and the Bill of Rights, the vast majority of Europe’s population were expert farmers and craftsmen – shoemakers and carpenters, stonemasons and smiths, bakers and butchers. Working with primitive tools, they were amazingly skilled at their respective trades. They did not attend schools or professional colleges, since none existed. Instead, they went through lengthy apprenticeships, starting at a teen age, helping their masters in exchange for food, clothes, shelter and the opportunity to learn all the skills associated with their crafts.

Most of the learning back in 1689 happened simply by doing, under the master’s watchful eye. The knowledge and skills one acquired in this way were unique – including carefully guarded professional secrets passed down from one generation of craftsmen to another. They were extremely deep but also extremely narrow. An expert shoemaker of the 17th century was able to produce stunningly beautiful boots but could hardly do basic math, to say nothing of engaging in a Socratic discussion of political or poetic subjects. With no general education, no Internet and no TV, few shoemakers of the 17th century had any idea of the world outside their native towns.

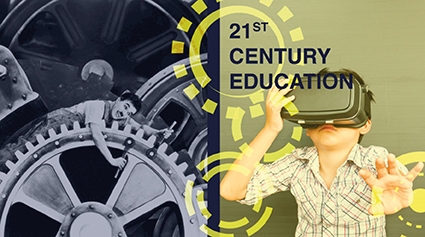

In contrast, Charlie Chaplin’s character in Modern Times does not have any unique skills or deep knowledge of any subject. He is a modern factory worker, trained to (very) quickly screw nuts onto pieces of machinery that move along an assembly line. He is a typical product of the modern, early 20th century general education system – itself an assembly line of factory workers and patriotic soldiers.

Modern schools are a 19th century invention, designed to quickly and efficiently mass produce people with the ability to man modern factories and trenches (also 19th century inventions). The kind of education modern schools were equipped to provide was, well, very standard, one-size-fit-all: the future scientist and the artist, the business genius and the agile mathematical mind.

Since modern factories did not require terribly skilled workers, schools focused on endowing students with shallow but relatively broad knowledge in a standard set of subjects, such as arithmetic, national geography and history, national language and literature, as well as prayer (in the national language!). Furthermore, administrative efficiency required that students be grouped by age rather than mental maturity, interest or ability, and that everybody be taught at the same pace.

Just like the standard Ford Model T was a technological solution for mass (middle class) mobility, modern schools were the institutional and technological solution for mass literacy and numeracy. On average, school graduates were not much better than 17th century apprentices at Socratic discussions. However, they could count, and were able to read jingoistic newspapers teaching them who is the enemy and why it is good to die for one’s country.

THE FUTURE OF LEARNING

What kind of knowledge and skills will our kids need in the 21st century and how will they be able to acquire them? Would they benefit from a modernized version of the “deep and narrow” individual apprenticeship model, such as homeschooling or its more radical, child-driven version, unschooling? Or, should we strive to continuously upgrade the “broad and shallow” national standards to which our schools are required to teach?

The answers to these questions are not clear, and they shouldn’t be for at least three reasons.

Firstly, the schooling methods of the past served a clear purpose: to train expert farmers, craftsmen, factory workers and patriotic citizens. Nowadays, it is hard to predict how the labor market (and nation states) will look like in 12 years, let alone 25 years. It is not even clear in which country our kids will choose to live. And, with advances in automation and communication technologies killing existing and creating new jobs at an ever increasing pace, the best schooling strategy might be one preparing students for an uncertain professional future. A future in which they are constantly pushed to learn new skills and ‘retool’. Training people for an uncertain future is essentially about training how to learn – independently and effectively.

Secondly, while there are not too many things we can definitely say about education models for the 21st century, one thing is certain: there will be many more ways to learn than ever before in human history. Standard curricula and classrooms – the Ford T Model of education – will surely continue to retain their significance in those parts of the world in which battling illiteracy will be the main function of public education systems. Elsewhere, the emphasis will inevitably shift towards more individualized, student-centered approaches allowing kids to discover and develop their unique talents. Not everybody ought to become mathematicians. Not all parents would want their kids to be subject to national propaganda.

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, technology ‘disrupts’ the very way in which we learn – anything. Over the past several years, I have observed my spouse Ania (PhD in Law from Krakow’s Jagiellonian University) successfully mastering several applied skills – from web design and graphic editing to woodworking and upholstery. She did so with the help of instructional videos, freely available online, and mentors – master craftsmen of the 21st century. She could not care less about formal degrees in any of the above subjects. Instead, she cares about her online portfolio and reputation.

YouTube and Google, Khan Academy, Coursera, EdX and many other providers of “massive open online courses” (MOOCs) make information, scientific knowledge and practical skills much more accessible than ever before. The best content – be it Khan Academy’s math and economics, or Dr. Najeeb’s anatomy and physiology lectures – are just one click away for anybody with an internet connection. We can easily “Google” recipes and disease symptoms, statistical procedures and necessary pieces of programming code. When in need of advice, we can approach interest-based online communities and forums. Very importantly, with instructional videos available on pretty much any topic, we can continue learning all our lives.

Will the ever increasing possibilities of fully individualized online and mentor-assisted learning cancel the need for schools as a collective learning framework? Probably not. Schools are likely to retain their function as a framework for learning basic social skills: discipline, stamina, teamwork, brainstorming solutions to problems or engaging each other in a Socratic discussion. Schools will provide access to lab equipment and technologies (for example, Robotics and 3D printing) that may not be accessible from everybody’s home. Finally, and ironically, schools may be reengineered to become a place for kids to take a break from tedious studies at home, meet other kids, have fun or work on joint projects.

AN IMPASS?

My younger kids, Jan (14) and Katya (13) are enrolled in a very good school, Ecole Française du Caucase – a well-financed and well-managed public French school. In addition to basic math, sciences and technology, Jan and Katya study the French language and literature, memorize France’s royal dynasties and rivers, and are (supposed to be) convinced that France is a cornerstone of global civilization.

As most kids of their generation, neither Jan nor Katya are particularly happy about their schooling experience. For one, they are terribly bored – they have little interest in memorizing French rivers or kings. Math and sciences, which they do enjoy, are taught at a snail’s pace, as is suitable for the weakest students in their classes. They complain about learning by rote, as well as too many uninspiring, repetitive homework exercises, leaving little time for the guitar or programming (Katya and Jan’s passions, respectively).

Don’t get me wrong. Jan and Katya are truly privileged to study in a public French school. The situation is far worse for kids in the public education systems of countries like Georgia and Armenia. Georgian and Armenian kids memorize their own rivers and royalties, and learn about the mythological eminence of their own ancient civilizations. Yet, Georgian and Armenian schools have neither great teachers nor great infrastructure. In fact, they are a huge waste of time for the vast majority of kids attending them.

DON’T MISS A GOOD CRISIS!

The impasse with public school reforms in Georgia, Armenia and other developing (and not only) countries around the world may be a blessing in disguise. If public schools continue to provide basic literacy and numeracy, according to their original (broad but shallow) 19th century design, the demand for higher level learning – deeper, more individualized and flexible – will be addressed by private actors, and through other means.

Armenia’s TUMO Center for Creative Technologies is an excellent example of doing just that. 14,000 TUMOians, ages 12-18, are currently enrolled in TUMO’s five centers in Armenia. There are no entry exams and no fees (TUMO is financed by rental fees paid by IT and media companies occupying the upper floors of its buildings). Instead of lectures, students follow an AI-controlled, individually tailored learning path with special workshops for those achieving expected outcomes. Instead of being grouped by age and squeezed into standard classrooms, students work in a seemingly chaotic but carefully crafted and totally inspiring open space, 600 at a time. They learn at their own pace. Building an online portfolio and investing in their ow future.

By Eric Livny