Double Pay for Nothing?

The ruling Georgian Dream coalition’s recent plan to gradually ramp up education spending to as much as 6% of GDP by 2022, has come as a surprise to many.

“Funding allocated to the education system will be increased annually and will reach its maximum by 2022, when we will hit the target of 6% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), i.e. one fourth of the State Budget. It will be ensured with a tailor-made piece of legislation – the Education Equality Act – which will be binding for the current and future governments of Georgia in order to keep investments this high flowing into the education sector and steadily increasing it every single year. Moreover, such voluminous public investment in the education system will lead to respective private sector initiatives and the education system will thus become dominant in our economy, ultimately with a 10-11% share.” - Georgian Prime Minister Mamuka Bakhtadze.

A REFORM LONG OVERDUE

Let us begin by stating the obvious: this proposal is long overdue.

Georgia’s general education system, the public segment of it, is among the worst in the world, judging by the results of international math and science tests, such as PISA (Georgia ranked 60th in science, 62nd in reading and 57th in mathematics, out of 72 countries included in the PISA of 2015).

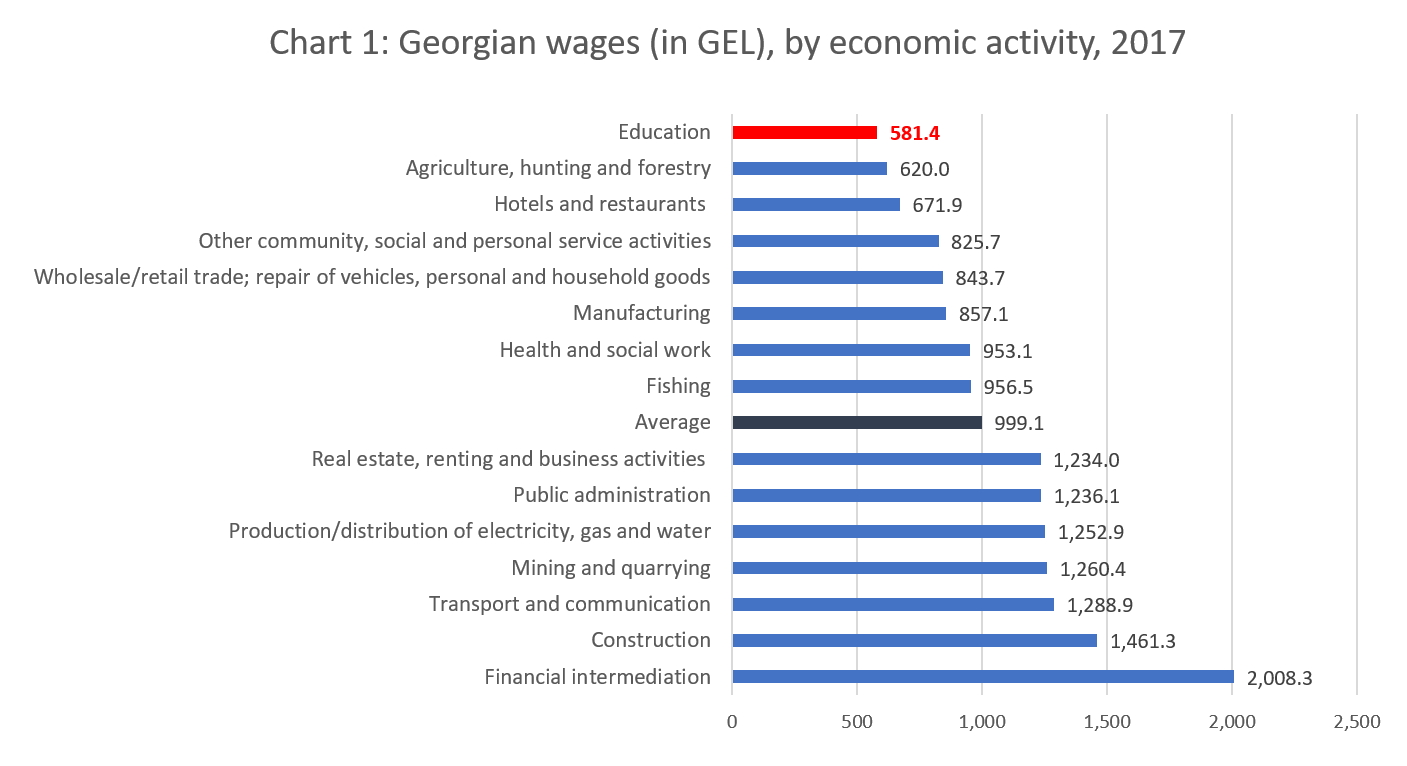

As shown in Chart 1, the Georgian educators’ average wages (581.4 GEL) were lower than in any other sector of the economy in 2017. Think of it: Georgian teachers earn less than the country’s peasants and hunters-gatherers, and less than 60% of the national average (about 1,000 GEL).

Not surprisingly, a very large share of Georgia’s teacher population lacks basic qualifications. And of those, many are past retirement age, but unwilling to retire despite low wages (since retirement benefits are even lower). In Georgia’s countryside, teacher jobs are an important source of cash, complementing in-kind income from subsistence agriculture. Teaching also comes with improved social status and side earnings from private tutoring.

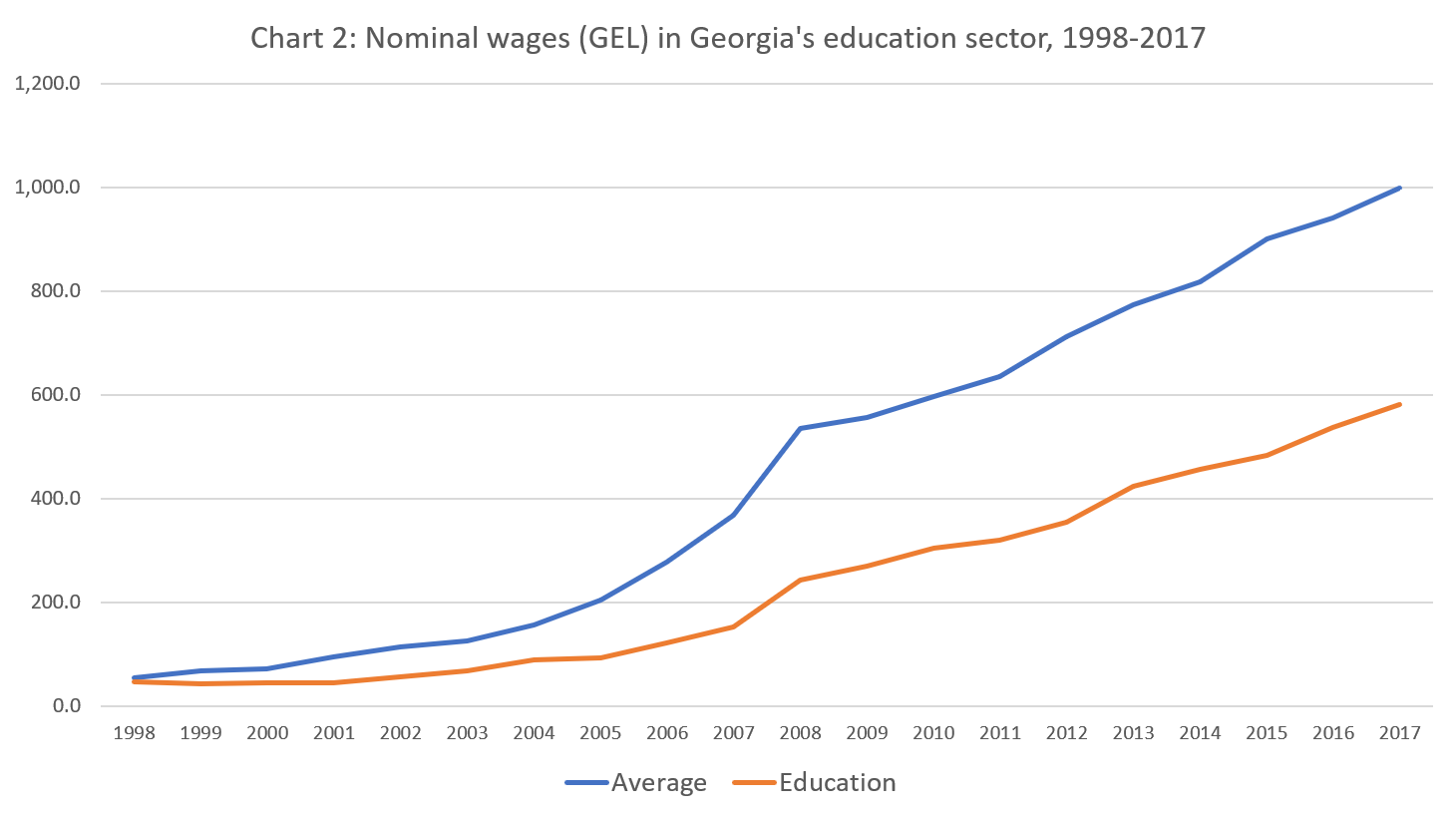

As shown in Chart 2, wages in the education sector did grow over time in nominal terms, albeit from an extremely low basis. Major adjustments occurred during the first part of Saakashvili’s rule: in 2002-2004 (growth of about 25% per annum), in 2006 (32%), 2007 (25%), and in 2008 (59%). An additional significant adjustment followed in 2013, the first year of the Georgian Dream coalition rule (19.1%). Still, wages in the sector failed to catch up with the rest of the economy, disincentivizing young people to enter the teaching profession.

Georgia’s public expenditure on education stood at 3.78 and 3.83% of GDP in 2016 and 2017. This is significantly higher than in the country’s entire recent history, and is close to the 2016 average of Europe and Central Asia (excluding high income countries) of 3.95%. At the same time, it is well below the target of 6% set by the Georgian Dream leadership. If this target is achieved by 2022, Georgia will find itself in a respectable club consisting of Nordic countries such as Iceland, Finland, Norway and Sweden, which all spend around 7-8% of GDP on education.

But we should ask two critical questions regarding the proposed reform:

• Firstly, how will the government finance the increase in education spending (as well as the planned increase in social pensions)? This question is of primary concern for Georgia’s macroeconomists and the International Monetary Fund.

• Secondly, what will be the impact of nearly doubling education spending on the quality of schools and the learning outcomes of Georgian students (however measured)? Below, I will try to find an answer to this question.

THE ROAD TO HELL IS PAVED WITH GOOD INTENTIONS

Money cannot buy love, but it can go a long way in improving education. For starters, money can buy infrastructure, which Georgian schools urgently need. But even more importantly, money can be used to increase (double and even triple) teacher wages. And this is exactly where it gets complicated.

Few would argue with the idea that underpaid teachers are unlikely to be good teachers. Indeed, UNESCO's flagship Education for All Global Monitoring Report (2013/14) claims that "[l]ow salaries reduce teacher morale and effort" and "teachers often need to take on additional work – sometimes including private tuition – which can reduce their commitment to their regular teaching jobs and lead to absenteeism".

But would higher pay necessarily increase teacher motivation and effort? A recent experimental study by the World Bank (Double for Nothing? Experimental Evidence on an Unconditional Teacher Salary Increase in Indonesia by Joppe de Ree et al, (2017)) suggests that this might not be the case, particularly when pay raises are 1) not conditional on going through a rigorous training program and passing an external examination, and 2) are difficult to reverse in case of substandard performance.

The authors provide experimental evidence on the impact of a large unconditional salary increase (a permanent doubling of the base pay) on the effort and productivity of incumbent teachers.

DESCRIPTION OF THE EXPERIMENT

Given the large fiscal burden of the policy, teacher access to the certification program was phased in over 10 years (from 2006 to 2015), with priority in the queue being determined by seniority. Thus, many "eligible" teachers had to wait several years before being allowed to enter the certification process. Working closely with the Government of Indonesia, the authors implemented an experimental design that took advantage of this phase-in. It allowed all eligible teachers in 120 randomly selected public schools to access the certification process and the resulting doubling of pay immediately; in contrast, teachers in control schools experienced the "business as usual" access to the certification process through the gradual phase-in over time. The study was conducted over a three-year period, in a near-nationally representative sample of 360 schools drawn from 20 districts and all major regions of Indonesia.

The experiment significantly improved measures of teacher welfare: teachers in treated schools had higher wages, were more likely to be satisfied with their income, and were less likely to report financial stress. They were also less likely to hold a second job, and worked fewer hours on second jobs.

Yet, despite this improvement in incumbent teachers' pay, satisfaction, and time available to focus on their main job (due to a reduction in second jobs), the reform did not improve either their effort or student learning. Teachers in treated schools did not score better on tests of teacher subject knowledge, and the authors found no consistent pattern of impact on self-reported measures of teacher attendance. Most importantly, they found no difference in student test scores in language, mathematics, or science across treatment and control schools. In other words, a reform that cost over 5% of Indonesia’s GDP was found to have absolutely no impact on the performance of incumbent teachers (the so-called intensive-margin effect).

GOOD INTENTIONS, BAD IMPLEMENTATION

As suggested by the authors, Indonesia’s education reform failed for political reasons.

“The certification process was initially meant to include a high-standards external assessment of teacher subject knowledge and pedagogical practice, with an extensive skill-upgrading component for teachers who did not meet these standards (featuring up to a year of additional training and tests). However, teachers' associations opposed the high-standards certification exams. Thus, by the time the final law and regulations were negotiated through the political and policymaking process, the quality-improvement stipulations had been highly diluted.”

The last thing the Indonesian government wanted was to pick a fight with the country’s powerful teachers’ associations. As a result, instead of going through high-standards external assessments, teachers were allowed to simply submit a portfolio of their teaching materials and achievements. Not surprisingly, very few teachers entering the certification process failed it. And, even those who failed the first attempt were all certified after a two-week training program, which mainly focused on helping teachers prepare the portfolios that would need to be submitted for the certification process. Thus, in practice, the certification process yielded a doubling of base pay with only a modest hurdle to be surmounted.

Furthermore, the large salary increase was not conditional on teachers' subsequent effort or effectiveness, but instead depended only on a one-time determination that the teacher met some certification criteria. Hence, for all practical purposes, the reform resulted in an unconditional salary increase for incumbent teachers. Not the best way to stimulate improved performance.

GEORGIA’S EDUCATION POLITICS

For Georgia to successfully combat poverty and regain its role as a cultural, scientific, and educational leader in the region (Bakhtadze’s goals), the country’s education reforms should not be sacrificed on the altar of political cost-benefit calculations. Alas, this is easier said than done.

So far, successive Georgian governments have had very little appetite for fighting the 60,000-strong Educators and Scientists Free Trade Union of Georgia. As a result, this powerful lobby has been very effective in blocking reforms seeking to establish rigorous certification exams and retire old and unqualified teachers. With highly contested parliamentary elections looming on the horizon, there is every reason to suspect that politics might once again interfere with excellent intentions.

Increased pay for new and qualified teachers should be a key component in any future education reform seeking to provide Georgia’s public schools with new blood and new ideas. However, a politically-motivated, unconditional increase in compensation, as may be lobbied by the Educators and Scientists Free Trade Union of Georgia, will achieve no impact while diminishing the fiscal space for other important programs (such as infrastructure investment). Such a populistic move will fail to produce an intensive-margin effect on incumbent teachers’ motivation and effort. If anything, it will strengthen their incentives to cling to their jobs, diminishing an extensive-margin effect associated with the potential arrival of new teachers.

By Eric Livny

About the author:

Eric Livny is Founder and President at Tbilinomics Policy Advisors, and Chair of Economic Policy Committee at the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC Georgia).