Russo-Turkish Standoff: Implications for Georgia

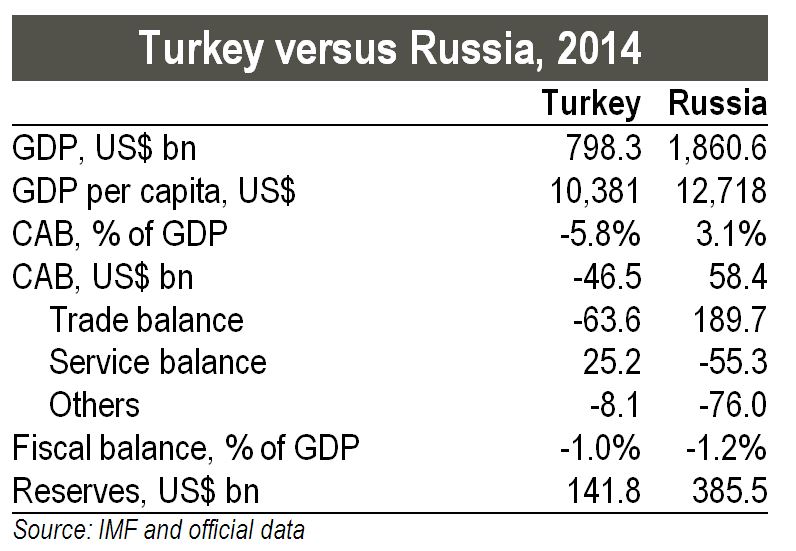

Turkey and Russia, Georgia’s two largest neighbors, have combined economies of US$ 2.7tn. The relationship between the two has worsened following the recent downing of a Russian jet by Turkey. Russia’s reaction was immediate – policies limiting Turkish imports, prohibiting charter flights to Turkey, and advising its citizens to avoid travelling to Turkey. These policies will impose costs on both economies, with some spillover to the neighboring countries. However, a detailed analysis indicates that the interdependence between Turkey and Russia is limited, with even fewer possible implications for Georgia. Turkey’s exposure to Russia is comprised largely of Russian natural gas imports and revenues from Russian tourists. While we do not expect Russia to cut gas deliveries, we think that fewer Russian tourists will travel to Turkey. Turkish exports of agricultural goods and textiles to Russia are likely to fall, but their share in total exports is low. Some of the loss will likely be compensated by the newly signed EUR 3.0bn deal between Turkey and the EU for managing Middle Eastern migrant inflows.

In 2014 Russia accounted for just 3.8% of total Turkish exports (US$ 5.9bn out of a total of US$ 157.6bn), which fell further to 2.5% in 10M15, as the economic contraction in Russia depressed demand for foreign goods. Turkish exports to Russia are dominated by textiles and clothing, fruits and vegetables, machinery and electronics, and transport. While the overall dependence is limited, the Turkish agricultural sector exhibits high vulnerability, with Russia accounting for 12.7% (US$ 1.1bn) of total Turkish fruits and vegetables exports in 2014 (US$ 8.4bn). With that said, Russia banned the import of only 18 items (including certain fruits and vegetables) from Turkey starting January 1, 2016. Exports of these items totaled US$ 0.8bn in 2014 (12.9% of total exports to Russia) and have declined 2.3% y/y in 10M15. This fall will accelerate in 2016 once the ban takes effect. However, given the low share in total exports, its impact should be minor.

Contrary to exports, Turkey is highly dependent on Russia for natural gas imports. Overall, Turkey imported 49.3bcm of natural gas in 2014, including 7.3bcm of liquefied natural gas (LNG). Slightly more than half of this gas demand (27.0bcm) was met by Russian gas, with the rest being imported from Iran (8.9bcm), Azerbaijan (6.1bcm), and other countries (7.3bcm). As Turkey used the largest share (48.1%) of its natural gas consumption for electricity generation, any disruption in Russian gas supply could negatively impact Turkey’s electricity generation. The country is expected to partially lessen its dependence on Russian gas starting in 2018, with an additional 6bcm of gas imports from Azerbaijan (already contracted).

It is unlikely that Russia will cut gas supplies to Turkey as natural gas exports are a major source of Russia’s export revenues and Turkey is its second biggest customer after Germany. Cutting gas supplies to Turkey would mean loss of revenues, which are already suffering from the US-EU sanctions. Russia’s weak external position due to the low oil prices reinforces this argument.

FDI from Russia in Turkey has generally been low. Of the US$ 101.4bn of FDI in Turkey from 2007 to September 2015, only US$ 3.3bn (3.3%) came from Russia. It is highly unlikely that Russia will constrain operations of Russian businesses in Turkey. Turkish investments in Russia are not expected to be hurt directly by sanctions either, as Russia does not intend to limit operations of Turkish subsidiaries registered as separate entities in Russia. However, an indirect impact on these companies cannot be ruled out, as they might run into problems procuring Turkish inputs and/or hiring Turkish personnel.

Suspension of major infrastructure projects is what could have a relatively strong negative impact. Turkish Stream – a multi-billion dollar project that was intended to expand the natural gas pipeline connecting Russia and Turkey – has already been suspended by Russia. While no official statement has been made, Russia may also opt to suspend the construction of a US$ 20bn nuclear plant in Akkuyu (Turkey), which it planned to finance fully. However, the Russian side has already invested some capital in the project and is contractually obligated to pay heavy penalties if it abandons the project. The medium- to long-term repercussions of the suspension of these projects would probably be felt in Turkey’s electricity market.

Turkish tourism exports will take the biggest toll from the strained Turkey-Russia relations. 4.5mn (12.5% of total) Russian tourists visited Turkey in 2014 (+5.0% y/y) and, based on our calculations, spent about US$ 3.7bn. With the economic contraction in Russia, however, the number of visitors to Turkey has already fallen 20.7% y/y in 10M15 to 3.2mn (11.1% of total). Unless the problems are resolved by spring 2016, the full impact of the drop in tourist arrivals should be felt in mid-2016, as October-April is the low season in the tourism industry in Turkey (in 2014, 83.1% of Russian tourists visited Turkey from May to September).

Our calculations indicate that annual losses from the standoff could amount to a maximum of 0.5% of Turkey’s GDP. However, this loss should be partially compensated by the EUR 3.0bn pledge by the EU to Turkey and a lower import bill due to sustained low oil prices, mitigating pressure on the exchange rate.

Expected Impact on Georgia

Transit of goods from Turkey to Russia through Georgia seems to be the only area that will suffer directly from the strained Russia-Turkey relations. Georgia has benefitted from the transit of Turkish goods through its territory, not only to Russia but also through Russia to Central Asia. With Russia banning certain imports from Turkey and limiting transit to Central Asia, Georgia could lose some revenue due to the drop in transit. However, the volume of trade through Georgia is not significant enough to have a major impact. Moreover, Azerbaijan recently offered its territory to Turkey for transit to Central Asia. If implemented, the new route can increase transit of goods through Georgia as some Turkish exports currently go through the Black Sea and Russia to Central Asia. Now this route can be changed to Georgia-Azerbaijan-Caspian Sea-Central Asia.

In some respects, Georgia could benefit from the new reality. Georgia can (i) partially substitute Turkish fruits and vegetables on the Russian market and (ii) attract some of the tourists who would normally go to Turkey. However, the benefits from these channels would only be realized in the middle of next year, as Turkey is a summer destination for Russian tourists, and redirecting vegetable and fruit exports could take a few months. Furthermore, Georgia could increase electricity exports to Turkey. As an emerging market, Turkey’s electricity consumption is increasing and demand is met mostly by natural gas-fired power plants. Failure to import more gas from Russia and possibility of suspension of the nuclear plant can pose a challenge for Turkey in meeting domestic electricity demand. In that scenario, Turkey will probably need to import electricity and Georgia could be one of the suppliers.

Alim Hasanov (Galt and Taggart)