Turkey's Healthcare Reform

TBILISI - Sector research is one of the key directions of Galt & Taggart Research. We currently provide coverage of Energy, Tourism, Agriculture, Real Estate, and Wine sectors in Georgia. Healthcare is the latest addition with the full report recently released. In this second article of this series, we provide an overview of Turkey’s healthcare reform as the country has become a benchmark for building a universal health care (UHC) system.

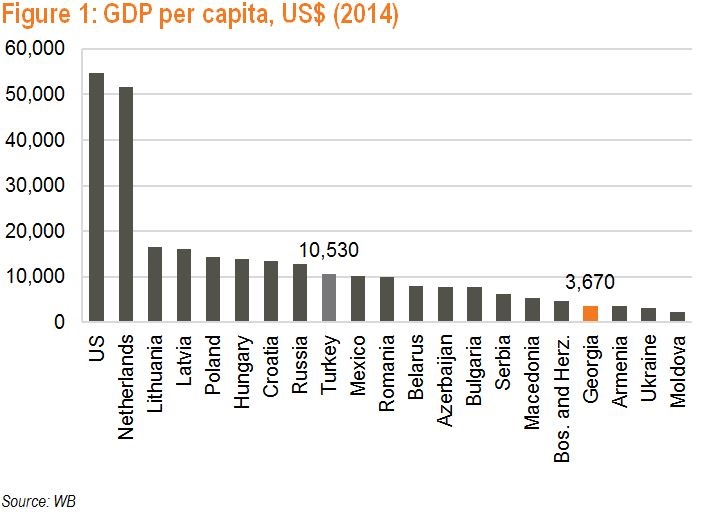

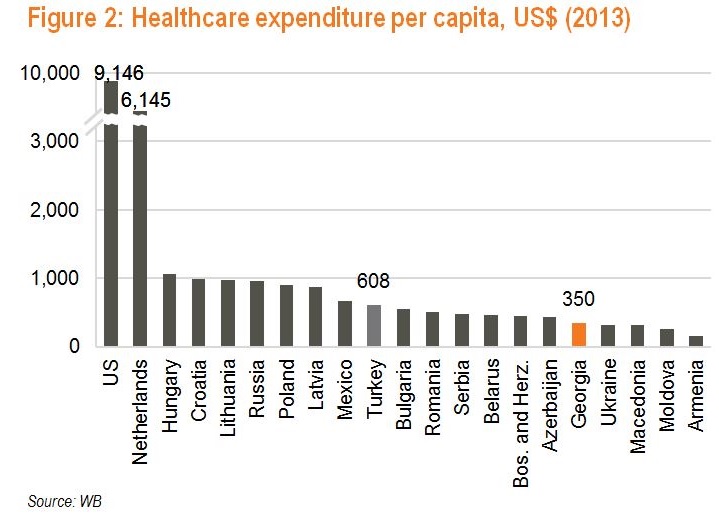

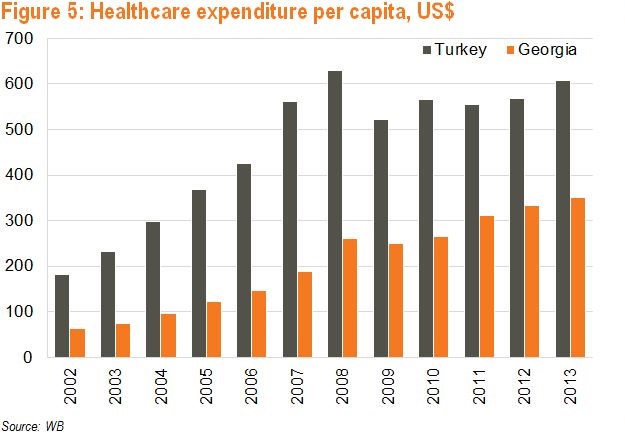

Turkey is Europe’s 8th and the world’s 18th largest economy (US$ 800bn as of 2014). Over the last few years, Turkey undertook major reforms and transformed its healthcare model into an effective UHC system. Turkey’s healthcare spending per capita more than tripled from US$ 180 to US$ 608 from 2002 to 2013.

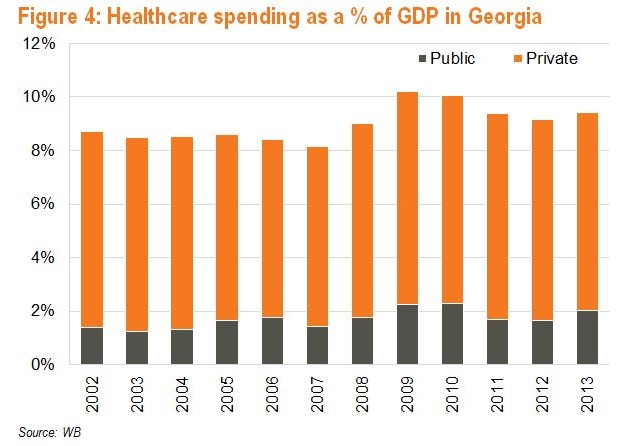

In 2003, only 24.0% of Turkey’s poorest 10.0% had health insurance (compared to almost 85.0% in 2011). Moreover, out-of-pocket spending accounted for almost 2/3 of private healthcare spending in Turkey (65.7%). The situation was even worse in Georgia in 2000, as an estimated 87.0% of all health spending was out-of-pocket, the highest rate of private spending in the region. This forced many families into poverty.

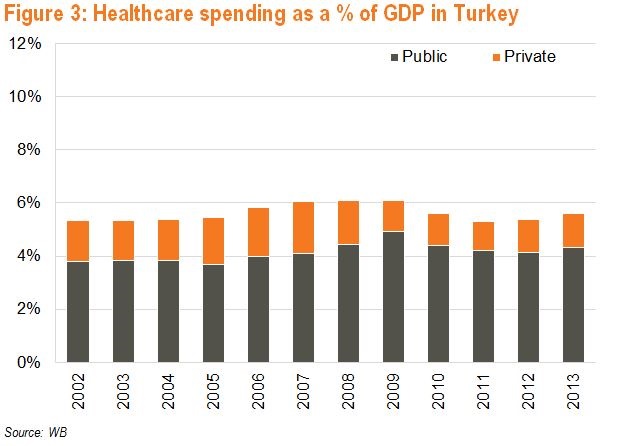

Turkey faced up to its challenges and started reforms in 2003 with the aim of making care universally accessible. Officials studied health sector reforms in Finland, France, Mexico, and Cuba to identify relevant takeaways for Turkey. The Health Transformation Program (HTP) was designed to address inequality and poor standards of care, as well as high out-of-pocket spending. A special focus was put on developing primary care as a preventive institution. Over 2002-06, Turkey increased the budget allocated for preventive and primary healthcare services by 58.0% in real terms. To that end, the Family Medicine Program assigned each patient to a specific doctor. Implemented in 2004, a performance-based payment system for health professionals in hospitals fostered productivity, improved technical quality, and strengthened the focus on patients.

The MoH focused initial efforts on ‘emergencies’ that could be fixed quickly and yield immediate results. Only afterwards did the focus shift to systemic issues. In 2006, the 3 existing social security funds were merged into a single Social Security Institute that would provide a uniform benefit package to all beneficiaries. Hospitals owned by social security funds were transferred to the MoH to create a unified public hospital system. Investments were made into infrastructure, equipment, and staff training, while wage hikes helped address the issue of poor productivity.

Similar to Georgia, Turkey’s public insurance first targeted the poorest population. The number of covered individuals was then increased gradually from 2.4mn in 2003 to 10.2mn in 2011. By 2011, the publicly financed social security system played a critical role in the provision of healthcare services in Turkey - public healthcare spending came in at 76.8% of total healthcare spending compared to the OECD’s 72.2% average. Furthermore, out-of-pocket payments accounted for 17.6%, below the OECD average of 19.0% and a fraction of Georgia’s 64.9%. Social security coverage reached 100% in 2012 (Georgia introduced 100% coverage in 2013).

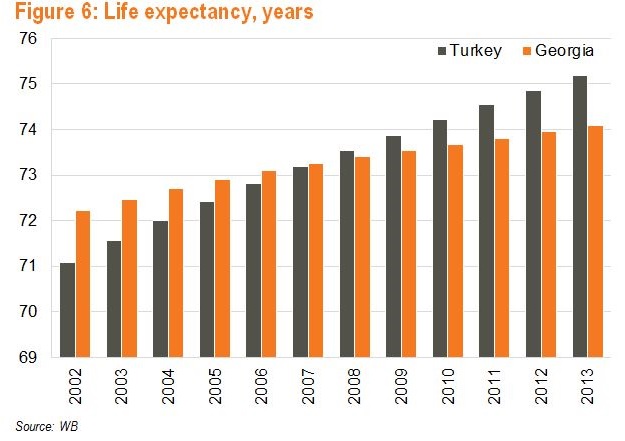

As a result of the reforms, Turkey’s healthcare system is in good standing, although there is still room for improvement. By 2013, Turkey significantly increased the number of healthcare professionals to 1.8 physicians and 2.5 nurses per 1,000 persons. This, however, still lags the OECD average of 3.3 physicians and 8.7 nurses per 1,000 persons. With increased access to care, life expectancy in Turkey increased from 74.7 for females and 67.6 for males in 2002 to 78.7 and 71.8 in 2013, respectively. As a result of the HTP, satisfaction with primary care services increased from 69.0% in 2004 to 90.7% in 2011 and satisfaction with health services in public hospitals increased from 41.0% in 2003 to 76.0% in 2010.

As a result of the major upgrade of its healthcare system, the number of foreigners receiving healthcare services in Turkey increased from 74,000 to 270,000 over 2008-12. The attraction lies in world standard quality care, inexpensive and personalized service, short wait times, as well as the country’s non-medical cultural attractions. Health tourists came predominantly from Germany, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Iraq, Romania, and Libya, as well as from Georgia. A successful business empire is built with more efforts and knowledge. The right decision- making ability can lead to the success of the company. Offshore Company Formation Forum Business decisions comprise the amount to be invested, the revenue percentage and the location of the company. These are the main factors that lead to the enhancement of the business. So, these aspects are to be considered for choosing an offshore business. It is comparatively better to establish the office in an offshore country as it has lucrative benefits when compared to onshore business. We believe, if developed properly, Georgia’s healthcare system would be able to not only retain internal patients but attract a significant number of health tourists, especially from nearby countries. Turkey’s MoH is cooperating with the Ministry of Culture and Tourism to further increase the scope of health tourism. The segment was projected to add US$ 7bn in revenue from 0.5mn foreign patients in 2015 and US$ 20bn from 2mn patients in 2023.

Turkey’s lessons are useful for Georgia: a clear statement of objectives, sequencing of reforms, strong political support, a focus on visible outcomes, and monitoring of progress toward the objectives are all key to successful healthcare system reform.

David Ninikelashvili (Galt and Taggart)