Overworked and Underpaid

By Maka Chitanava and Nino Doghonadze

The ISET Economist, a blog about economics in Georgia and the South Caucasus by the International School of Economics at TSU (ISET)

WORKING OVERTIME…

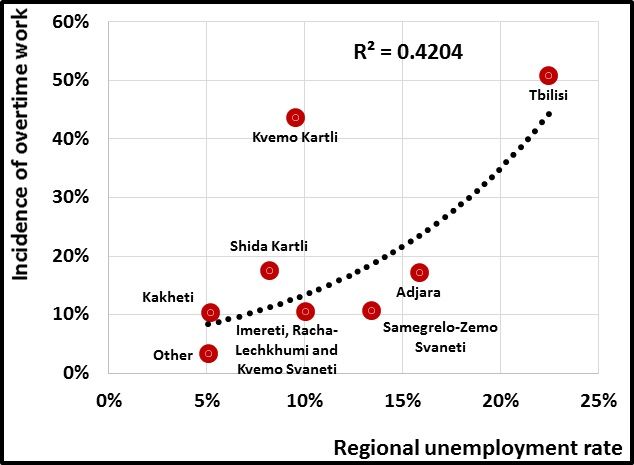

In 2014, 22% of Georgia’s working adults reported having worked more than 40 hours per week, i.e. working overtime. This many not sound like a lot, but, as any average figure, it hides a great deal of geographic variation in the incidence of overtime work. Very few people work overtime in places where there are almost no jobs, such as Kakheti or Racha. Conversely, more than 50% work over 8 hours/day in the dynamically developing Tbilisi, and as many as 44% in the adjacent Kvemo Kartli.

With so many people doing it, working overtime is becoming the norm, and considered mandatory in many occupations. For example, in quite a number of government agencies, meetings and consultations routinely start after normal office hours, and often run until after midnight. Symptomatically, when interviewing for jobs with these institutions, candidates are expected to demonstrate ‘flexibility’ when it comes to working overtime.

Having earned themselves the reputation of a lazy nation, Georgians may deserve to be overworked. One may even think that making Georgian alpha males work 12 or 15 hours a day may be a great way to teach them Protestant work ethics. Yet, while perhaps justified, this approach would only work to a point. Fairness considerations aside, overtime workers are not very productive workers. And due to unhealthy lifestyles and permanent work-related stress, their mental and physical health would quickly deteriorate, making them unfit for any job.

So, why do we work overtime?

WORK ETHIC, MONEY OR FEAR OF UNEMPLOYMENT?

It may well be the case that some of us are workaholics and enjoy every extra hour spent in the office or on the factory floor. However, it is hard to believe that 50% of Tbilisi residents derive pleasure from slaving themselves at work.

Another possibility is that people want the extra money that comes with overtime work. This theory finds some support in the fact that, in 2014, overtime workers earned, on average, 246 GEL more than regular-hour full-time workers. Yet, a very different picture emerges if we consider regionally disaggregated data. Overtime workers may, indeed, earn more than the national average, but only because the vast majority of them live and work in Tbilisi and its vicinity, where wages (and the cost of living) are higher than elsewhere in the country. The differences in the earnings of overtime and regular-hour workers within the same region are negligible. When considering income from primary employment in Tbilisi, we find no statistically significant differences at all. The same is true for Mtskheta-Mtianeti. As for Kvemo Kartli, the extra earnings associated with overtime work amount to a meager 59 GEL per month. Thus, if anything, the bulk of overtime workers are overworked and underpaid!

If most Georgians are not workaholic, and if overtime work is not adequately remunerated, the main explanation we are left with is that overtime work is simply a way for people to secure their jobs. Indeed, by working overtime, employees may be trying to impress their bosses with their diligence and devotion. “Look”, they signal, “no matter how much you try, you won’t find anybody better in the long line of job seekers outside the factory gate”.

A quick look at the regional unemployment and overtime work statistics (see chart) lends strong support to this line of reasoning. The incidence of overtime work (measured as a share of total employment) is correlated with unemployment. In other words, the higher the rate of unemployment, the more people tend to work overtime. The only ‘outlier’ in this regard, Kvemo Kartli, exhibits the second highest incidence of overtime work (43%) despite being fairly low on unemployment. Yet, Kvemo Kartli’s exceptionalism only serves to prove the rule. Most of its overtime workers (e.g. those living in Rustavi) are, in fact, taking a daily commute to Tbilisi and are subject to the same psychological pressures as most other workers in the capital.

The fact that involuntary unemployment can motivate workers to work harder is yesterday’s news in economics. For example, according to Carl Shapiro and Joe Stiglitz (Equilibrium Unemployment as a Worker Discipline Device), unemployment may be the result of uncoordinated decisions by firm managers to raise wages above what their workers would receive at competing firms. The idea is that higher wages make it costly for workers to shirk and thus risk the loss of their well-paying jobs. Since all firms raise wages, and workers work harder (and longer hours), the new equilibrium will be characterized by a higher level of (involuntary) unemployment. And since all workers will be paid the same (higher) wage, unemployment will substitute for wages as a worker discipline device.

HOW MUCH SHOULD WE WORK?

According to a recent ILO survey, the 40-hour workweek is the norm in 41% of countries. We – and our bosses – are all used to 8-hour work days and 40-hour workweeks, and rarely question their rationale. Yet, what is so “magic” about these numbers?

As a matter of fact, Sweden’s recent shift to a 6-hour working day challenges our current perceptions of what may be optimal from the point of view of workers’ motivation and productivity. It goes without saying that shorter work days would give people more time to invest in their families, enrich their personal and social lives, and thus contribute to a sense of good balance and happiness. But, as confirmed by the experience of Swedish employers who introduced shorter work days more than 10 years ago (without waiting for a government decree to), working less hours may also result in lower staff turnover, higher productivity and higher profits.

The 40-hour workweek was certainly a great achievement of the 20th century. The first business to implement a 40-hour workweek was the Ford Motor Company. In 1914, Henry Ford stunned the world by not only cutting the standard workday to eight hours, but also doubling his workers’ pay. Surprisingly for many, this resulted in his company’s profits doubling within two years, encouraging other businesses (and countries) to follow suit.

While perhaps suitable for the 20th century, it is not at all clear that 8-hour workdays are a good fit for the 21st century as more and more routine tasks are performed 24/7 by robots, fully automated production lines, and computers. It is not at all clear that 8-hour workdays are best at a time when information technologies and automation are rapidly transforming the working environment and human culture.

* *

In his “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren”, John Maynard Keynes had famously predicted that in a world of material abundance, towards which we are inexorably advancing, humans will be preoccupied with the challenge of filling their life with meaning. Those people will be able to enjoy the world of abundance, he argued, “who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life … Three-hour shifts or a fifteen-hour week may put off the problem for a great while. For three hours a day is quite enough to satisfy the old Adam in most of us!” Keynes wrote in 1930.

While hardly living in an age of material abundance, we, Georgians, should also keep in mind the question of purpose. Are we working to live or living for work?