Georgian Exports – Untapped Potential

Growth in Georgian merchandise exports has averaged about 20% over the past decade, but its share to GDP has not increased significantly. The share of services exports to GDP, on the other hand, has almost doubled, driven by growth in tourism and transport receipts. While Georgia has experienced impressive growth over the last decade, with the exception of the years affected by the global crisis and the post-election related uncertainty, the share of exports to GDP remained significantly lower than in peer countries. During 2005-2013 Georgian goods export share to GDP averaged 21%, while the same figure was 75% in the Slovak Republic, 53% in the Czech Republic, 52% in Lithuania, and 33% in Latvia. During the same period, imports expanded at a faster rate, especially during the boom years of 2003-2007, fueled by large capital inflows and credit growth. While Georgian exports increased 4x in nominal terms to US$ 2.9bn in 2014 from 2004, employment-generating processed product exports remained secondary, as commodity structure was dominated by used cars and resource based metals and minerals. Though there have been significant changes in Georgian export structure and diversification of destination markets in recent years, Georgia has not yet demonstrated success in tapping international markets, despite remarkable improvements in the business environment, progress in trade liberalization, enhancement of trade-related infrastructure and streamlining of customs procedures since 2004.

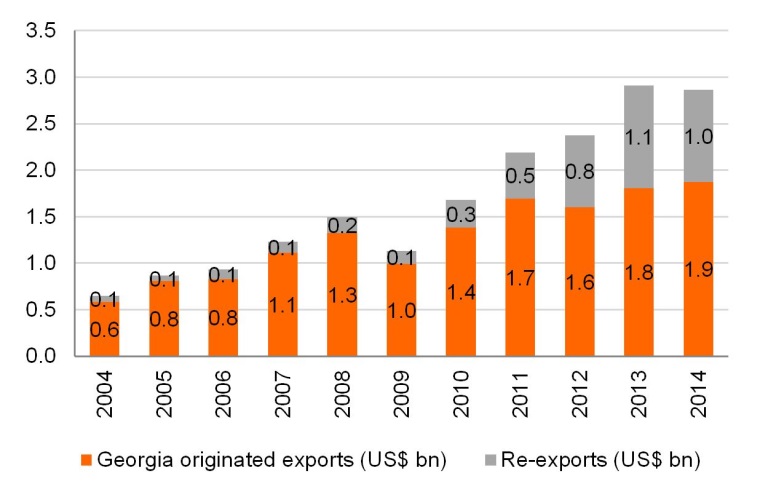

Re-exports vs. Georgia originated exports

To understand Georgian export performance, it is essential to decompose the export commodity structure. Over the past decade, used car exports to neighboring Azerbaijan and Armenia (as well as Kazakhstan until 2012) made up a considerable part of Georgian exports. Re-exports, dominated by used cars, increased 18 times to US$ 1.1bn in 2013 from 2004 and their share picked up from about 10% in 2004 to almost 40% of total exports. In the same period, exports originated in Georgia increased just threefold to US$ 1.8bn. In 2012-2013 re-export growth considerably overtook Georgia originated export growth, despite the reopening of the Russian market in 2013. Yet the 1.6% y/y drop in Georgia’s exports in 2014 was solely attributed to a decline in re-exports (as Azerbaijan introduced restrictions on used car imports in April 2014), as Georgia originated export growth slowed but remained positive. The re-exported used cars are imported from various countries and minor repairs are performed in Georgia. Such renovation activities, as well as the transport and logistics for these goods, do create some local value added. Such value creation was made possible by the implemented reforms, which helped Georgia become a regional marketplace for cars. While recent regional economic troubles significantly weighed on car re-exports, Georgia’s functional hub economy, with developed logistics and transport infrastructure, has helped shore up opportunities for new re-export commodities, like copper and pharmaceuticals, since 2013. Though re-exports of used cars decreased 63% y/y, re-exports of copper and pharmaceuticals increased 19% y/y and 297% y/y, respectively, in 4M15. Given these trends, it is likely that re-exports will continue to fuel Georgia’s export growth and government policies should be aimed at further enhancing the platform for current and potential trade partners.

Figure 1: Georgia’s export structure

Source: GeoStat

The Russian market

Another big change in Georgian exports has been a reorientation from the Russian market after the 2006 embargo, which caused the share of exports to Russia in total exports to decrease from 18% in 2005 to 8% in 2006 and 2% in 2008-2012. The embargo forced Georgian producers to redirect exports to other CIS countries, the EU, and the Middle East. Exports to Russia picked up in 2013 as Russia opened its borders to Georgian products, but accounted for only 6 percentage points in the 22% total export growth in 2013. Even without Russia, Georgian exports have more than tripled since 2005 to US$ 2.9bn in 2013. With the recent economic turbulence in Russia, the exposure to the Russian market (wine, mineral water and agricultural products) is once again receding. In 5M15, Russia’s share in total Georgian exports went down by 2.8 percentage points to 6.4%, compared to the same period last year.

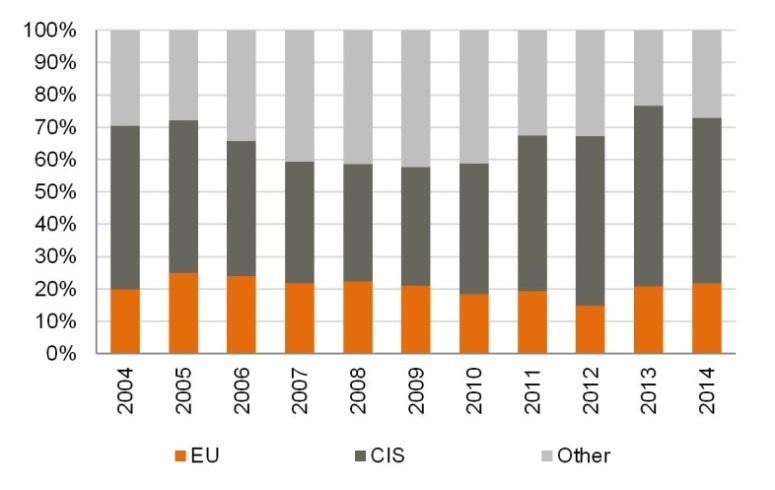

Exports to the EU and other countries

Exports to the European Union and Turkey offer significant upside potential. The share of Georgian exports to the EU in total exports has remained relatively flat at about 20% over the past decade. This low share suggests that the EU market is untapped and the free trade agreement, which went into effect in September 2014, will support export growth. A study by the EU suggests that the DCFTA may increase Georgian exports 9-12%. 5M15 trade outcomes indicate that the EU market for Georgia’s products remained stable compared to the CIS markets. The share of exports to Turkey decreased to 8.4% in 2014 from 18.3% in 2004, indicating that Georgia has the potential to increase export flows to its immediate neighbor as well. The share of Georgian exports going to USA, China and Canada has increased moderately over the past decade and as shares are still low, there is further room for expansion.

Figure 2: Export by country groups

Source: GeoStat

Going forward

Looking at Georgia’s export performance, a key question is how to take advantage of global markets and expand exports. First, the trade enhancing reforms to be implemented under the EU DCFTA can be particularly important for producing high quality products and increasing Georgian exports. Second, attracting FDI in export generating sectors is vital, as Georgia lacks capital and knowledge to produce and export more sophisticated commodities. To that end, continued improvement of the business environment and the economy’s competitiveness is essential. Policy makers have to be extremely cautious when considering new regulations on the business sector with potentially harmful effects. In this regard, the 2014 tightening of visa rules provides a positive example, as the government acknowledged its mistake and reversed course through the latest amendment. Third, it is essential to stick to the floating exchange rate regime. Letting the lari to depreciate against the dollar starting from November 2014 allowed the exchange rate to absorb most of the shocks and relieve pressures on the real economy. The depreciation prevented exports from becoming too expensive, as Georgia’s trading partners’ currencies experienced sizable depreciation as well. The resulting depreciation of the real effective exchange rate may even encourage Georgian producers to compete with imports and the ensuing profitability could encourage the production of new export goods.

Eva Bochorishvili (Galt and Taggart)