Breathing in Tbilisi

By Maka Chitanava

The ISET Economist, a blog about economics in Georgia and the South Caucasus by the International School of Economics at TSU (ISET)

Just recently, I signed an online petition initiated by volunteers, about preserving Tbilisi’s former hippodrome as a recreational zone, a kind of mini-Templehofer field for Tbilisi residents. I am not completely hopeless, but we may not have the collective power to protect this 62-hectare territory in central Tbilisi against the much better organized and wealthier developers who have been coveting this piece of land for more than a decade. If this pessimistic scenario unfolds, Tbilisi will remain polluted… a city for cars, not people: towers, unregulated construction everywhere, no proper urban planning, no clear zoning rules, few playgrounds, even fewer green spaces… A sad story indeed.

|

HOW IS AIR POLLUTION MEASURED? The World Health Organization (WHO) measures air pollution by the mean concentration of particulate matter (PM), i.e. particles in the air with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 μm or less (PM10) and 2.5 μm or less (PM2.5). Those particles are things like organic dust, airborne bacteria, construction dust, and coal particles from power plants. The “10” and the “2.5” refer to microns. Particulate matter is associated with a broad spectrum of acute and chronic illnesses, such as lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cardiovascular diseases. Worldwide, it is estimated to cause about 16% of lung cancer deaths, 11% of COPD deaths, and more than 20% of ischemic heart disease and stroke. Note that PM does not include gas pollutants such as ozone and NO2. |

THE AIR WE BREATH

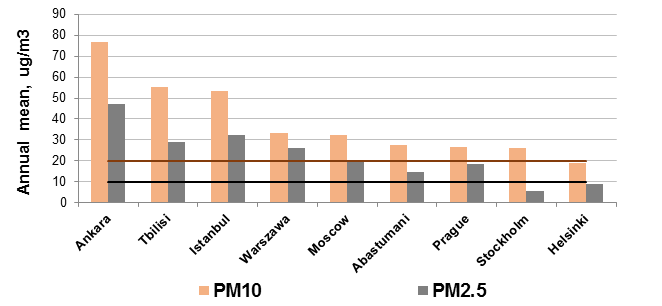

According to the World Health Organization’s city pollution database (2016), more than 80 percent of people living in urban areas that monitor air pollution are exposed to air quality levels that exceed the WHO limits (the database covers 3,000 cities in 103 countries). Not surprisingly, using MP10 data, Tbilisi ranks #473 as one of the most polluted cities. Using MP2.5 data, Tbilisi ranks #571. Tbilisi’s annual mean values for MP10 stand at 55 mg/m3 and at 29 mg/m3 for MP2.5, while according to WHO’s Air Quality Guidelines they should not exceed 20 and 10 mg/m3, respectively.

AIR QUALITY AND THE CITY’S GREEN LUNGS ARE PUBLIC GOODS!

My pessimism regarding Tbilisi’s future was reinforced recently. Two months have passed since Guerrilla Gardening Tbilisi started a new wave of protests at Tbilisi City Hall. Their protest was triggered by the felling of century-old trees in the city center in order to construct a 42-storey tower. Protesters demanded from the Mayor and City Hall that its Ecology and Landscaping department be staffed with qualified personnel and this case be properly investigated. So far, no (visible) action has been taken, making one wonder whether it is public interest that City Hall is mainly after.

The quality of air, as well as parks and recreational areas, fall into the category of “common resources” that are equally accessible to all members of a society. There is an element of tragedy embedded in the notion of such resources precisely because of their shared nature: when following their own self-interest (and nothing else), individuals have the tendency to overuse and deplete common resources simply because they think that, well, it is only them doing it. Felling one tree may not be such a big deal in the “grand scheme of things.” But if everyone cuts (just) one tree, we will all suffer enormously.

The most straightforward solution to this “tragedy of the commons” is to grant property rights over a common resource (say, a park) to an external authority – a private owner or the state, who will make sure to protect and restrict access to the resource they own or manage in order to maximize (private and public!) gains over time. The Georgian people have opted for the public management solution, granting the State of Georgia the responsibility of managing their common resources in order to maximize social welfare and avoid a tragedy of the commons.

Thus, in an ideal world, governed by wise state institutions and a benevolent local government, Tbilisi citizens should be assured that their common resources, such as national parks and recreation areas, are well protected. The fact that they are not suggests that Georgia’s state bureaucracy a) lacks the ability to manage our common resources, or (b)is not willing to serve the common good (serving somebody’s private interests instead), leaving people with no fresh air to breath. In fact, options (a) and (b) are not mutually exclusive.

Development and construction does often come at a cost to the environment or cultural heritage (another type of common resource). City Hall may have reasons to believe that felling a few old trees or redeveloping a major recreation area in Tbilisi can promote economic growth, job creation, etc. That being so, Tbilisi citizens have the right to get a proper account of the in-depth economic analysis City Hall undertakes before deciding on such sensitive matters as the fate of the city’s only major recreation area. They have the right to know whether their health and recreation needs are being properly taken into account when awarding lucrative construction licenses in the city center.

Tempelhofer Feld is a good example of how citizen activism can work in reality. During the 2011 local elections, former Berlin mayor Klaus Wowereit proposed to use the field to locate new commercial areas and offices, 4,700 homes and a large public library. Planners promised they would only build on 25% of the site, leaving 230 hectares as a recreational area. His program included a promise that the new apartment blocks would include affordable housing.

BUT, Berliners rejected Klaus Wowereit’s plan for large-scale property development on their beloved Tempelhof Feld. In a referendum aimed at preserving the green space, almost 65% voted against the proposed development plans. In this referendum, Berliners voted not only for preserving one particular green space; they clearly stated their preference for a green future for their city.

This is what we lack in Tbilisi. Tbilisi citizens are not used to stating and defending their preferences; they are overly focused on partisan elections and forget to act as citizens. Apparently, only 8,000 people signed the petition for preserving Tbilisi’s former hippodrome area as a recreational zone; 8,000 out 1.1 mln residents. Thus, the tragedy of commons appears to be right there, in our minds.