“Friendship Bridge” – For or Against Gravitation?

By Irakli Shalikashvili

The ISET Economist, a blog about economics in Georgia and the South Caucasus by the International School of Economics at TSU (ISET)

The official visit of the Armenian President last week was concluded by a splashy announcement that the building of the “Friendship Bridge,” a new infrastructure project approved by the Georgian and Armenian Governments in late 2014, will start construction in 2017, and will be completed in under two years. The Georgian Prime Minister and the Armenian President have reportedly discussed a range of other opportunities to deepen economic and trade relationship between the two countries and support business community engagement in this process.

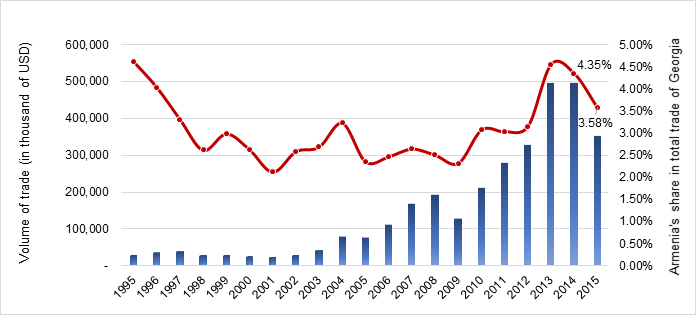

This excitement might come as a surprise in these times of diverging paths of the regional integration policies of the two countries. In 2015, Armenia joined the Russian-led customs union – the Eurasian Economic Union (EaEU), while Georgia had already signed a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with the EU (June, 2014). 2015 also saw a drastic decline in trade volume between the two (see Figure 1 below), in absolute terms (-29%, in USD), and in the share of Armenian goods in Georgia’s total trade volume (from 4.35% to 3.58%). The question naturally arises: will “Friendship Bridge” end up being mostly a transit route between Armenia, Russia and the rest of the EaEU, or will it serve as a tool for strategic trade and economic partnership between Georgia and Armenia?

Figure 1. Trade Volume between Georgia and Armenia

Source: Geostat

STRONG “GRAVITATIONAL FIELD”…

Many similarities between the Georgian and Armenian economies have emerged from geographical, historical and anthropological circumstances, which according to trade economists create a unique set of favorable conditions for deeper economic integration. The gravity model of international trade was first introduced by Jan Tinbergen in the paper, “An analysis of world trade flows, in shaping the world economy” in 1962, which uses key country characteristics to explain overall trade volume between two countries. According to the model, trade between two countries is proportional to their respective sizes, measured by their GDP, and is inversely proportional to the geographic distance between these countries. Though important, these two characteristics proved to be incomplete in terms of explaining trends in trade flows across the world. As a result, over time the model acquired a more diverse set of variables (such as common language, common borders, landlocked, island, land area, common country, GSP (Generalized System of Preferences), joint FDI stocks, joint trade with all partners, partnership with EU, NAFTA, etc.) which served to better explain trade flows between countries.

According to the gravity model, given that Armenia and Georgia are geographically and historically very close neighbors, with common borders, and that for Armenia, Georgia provides unique access to foreign markets, and that both countries have very similar economic structures, we can infer that they both benefit from quite a strong “gravitational field” for bilateral trade.

…BUT DIVERGING PATHS…

Both Georgia and Armenia have been an important destination for the other country’s exports, supported by the bilateral Free Trade Agreement (FTA), signed in 1995. The FTA, effective to-date, precludes any tariffs or quotas on products traded, and allows for the free transit of goods. Recent commitments to mutually exclusive free trade agreements, DCFTA for Georgia, and EaEU for Armenia, will have the most immediate implications on trade terms between the two countries due to the tariff and non-tariff barriers each agreement entails.

The FTA between Georgia and Armenia is in principle incompatible with EaEU membership, but an explicit clause in the agreement allows Georgia to trade freely with Armenia as long as the FTA remains effective. However, Georgia will only be able to export domestic products tariff-free to Armenia. Re-exports of foreign produced goods will be subject to increased tariffs. In the long run, non-tariff barriers erected through product standards to which each country is committed to comply with by 2020-2022 may lead to increased compliance costs for both Georgian and Armenian exporters.

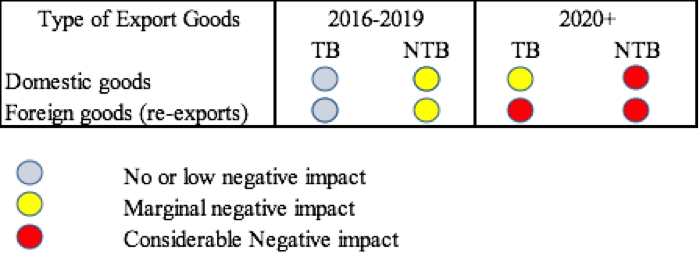

The German Economic Team-Georgia (GET), in the 2016 report “Trade between Georgia and Armenia: Business as Usual?”, claims that the different trade orientations will have short- and long-term consequences for Georgian-Armenian trade dynamics. Table 1 below summarizes short-term and long-term consequences for both tariff barriers (TB) and non-tariff barriers (NTB) on exports of domestic and re-exports of foreign goods. In the short-term, higher tariffs will be imposed on only a few foreign-produced goods, so tariff barriers will have low to no negative impact on total exports to Armenia. Non-tariff barriers, such as more demanding customs procedures for non-EaEU countries, is expected to bring about marginal negative impact. In the long run, on the other hand, the elimination of tariff exceptions for re-exports will cause an additional negative impact on exports from Georgia. Due to Georgia’s strategic importance as a transit route for Armenia’s exports, it is highly likely that Georgia-Armenian FTA will remain effective, in which case Georgia will continue to benefit from duty-free access to the Armenian market. However, since Georgia will conform to DCFTA standards, and Armenia will apply EaEU regulations, the compliance costs for exporters will increase, mainly in agriculture sector, because of the different product standards and safety requirements the agreements entail. This is expected to have considerable negative impact on trade between Georgia and Armenia.

Table 1. Summary of Impact Analysis based on GET (2016)

According to GET, part of the decline in export structure in Georgia can already be explained by Armenia’s EaEU membership. In 2014, 9.8% of total Georgian exports were directed to Armenia, while in 2015, this number dropped to 7.1%. 77% of this decline was due to drop in re-exports, mostly of used cars, which according to the authors, resulted from increased administrative and financial burdens at the EaEU customs border.

… AND SENTIMENTS

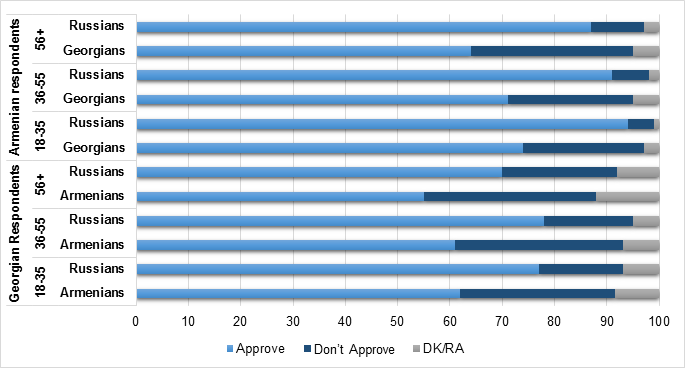

The deteriorating economic ties of Armenians and Georgians is exacerbated by noticeable distrust of each other. According to the Caucasus Barometer, an annual survey conducted by the Caucasus Research Resource Center, more Armenians, as well Georgians, approve of doing business with Russians rather than with each other (see Figure 2). Luckily, the share of respondents who do not approve doing business with each other is significantly smaller for young generation of Georgians and Armenians.

Figure 2. Approval of Georgians and Armenians Doing Business with Each Other and Russians

Source: Caucasus Barometer 2015 (CRRC)

ON THE POSITIVE SIDE…

Georgia’s duty-free access to the EU carries the promise of attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in the production of goods for export to the EU market. For Armenia, Georgia can serve as a duty free “export platform” for EU-oriented goods and services. Export-platform investment can be done by setting up an entire production chain or some elements of it (not necessarily the final stage of production). The type of investment (sector, production phase) will depend on the “Rule of Origin” regulations that apply in each specific case (i.e. the share of Georgia, EU and/or other eligible countries in the final value of the product), Georgia’s comparative advantages in production inputs (labor, land, water, energy, natural resources), and, of course, investors’ know-how.

While still comprising a minor share (0.77% in 2015) of Georgia’s total FDI, 2014 and 2015 saw a remarkable increase in Armenian FDI relative to previous years (157% increase over 2012-2013). More time is required to see whether this short-term surge in investment flows is maintained and could be attributed to export-platform investment.

TO CONCLUDE…

Despite recent evidence pointing to diverging paths of trade policies, Georgia and Armenia have significant strengths that can be utilized in order to take advantage of the opportunities their economic and political partnership makes available. If left unattended, adverse external circumstances and the weaknesses discussed above could take a toll on the economic development of these countries. Therefore, we hope that the “Friendship Bridge” will bring together the Georgian and Armenian governments to work on coordinated policies of economic integration, connect Georgian and Armenian businesses to take advantage of the opportunities each country has to offer, and supply Georgian shops with the second best water in the world (after San-Francisco) from Dilijan (Rubik Khachikyan, 1977).