Georgian Judges Go Soft On Poachers

One evening in the southern Georgia village of Mlate, six hunters drove out into the forest. They parked and then scattered, looking for game. One of them, Akaki Chagunava, shot twice and killed a brown bear - an animal on the country’s Red List for protected species.

They got caught by local environment inspectors and were taken to court. The six hunters denied planning to kill a bear. “We could not imagine that Chagunava would kill a bear,” said fellow hunter Gocha Kapianidze. “We were hunting for rabbits.”

The other hunters used their right to remain silent. The judge declared them and Kapianidze innocent and returned their guns.

Chagunava, who killed the brown bear, was prosecuted by another judge at the same court. “The subject fully acknowledges the nature of the crime of which he is accused and the punishment that awaits him,” according to the court document.

As a result, Chagunava and the prosecutor agreed on a plea bargain. The poacher was given two years’ probation and did not have to pay a fine.

According to Georgian law, there is a stiff fine for killing an animal on the protected list. For bears it is 10,000 GEL (about $3,876).

Hunting is legal in Georgia. It is possible to kill large mammals at hunting reserves and migratory birds anywhere. It is illegal to hunt during mating seasons.

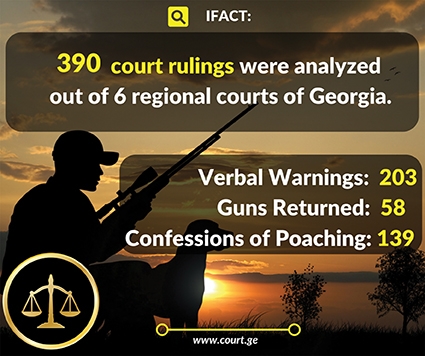

“iFact” requested court decisions on illegal hunting and fishing in the last five years from six regional courts in Georgia.

Out of 390 court decisions, only five were classified as criminal cases for killing protected species; the rest faced minor administrative charges. All five criminal cases ended in plea bargains. No poacher paid a huge fine and nobody was sent to prison.

Georgian laws on illegal hunting provide a maximum three years of imprisonment. Fines start at 10 GEL (about $3.85) for common species up to 13,000 GEL (about $5,000) for killing East and West Caucasian tur (an antelope goat), considered the two most valuable subspecies in Georgia. Both are listed as “endangered” by the IUCN, International Union of Conservation of Nature.

Poachers usually acknowledge all court charges. In return, their fines often are reduced or not given at all.

Out of 390 cases analyzed, 139 hunters confessed and asked to be assessed a small fine or none at all. In 58 cases guns and illegal fishing nets were returned to poachers. In 203 cases, only verbal warnings were given and no fines.

Some patterns emerge in these cases:

A representative of the Ministry of Environment and Natural Protection, which files the case with the court, often does not often appear at the hearing;

Poachers almost always acknowledge their crime, and as a result are often exempted from any fine;

In dozens of situations, guns or fishnets are returned even when the judge decrees an administrative charge against the poacher;

In many instances, hunters have a gun without legal possession;

In many instances, hunters do not have the license receipt for hunting certain species [for instance, 10 GEL ($3.85) for migratory birds].

The main body of the court decisions read the same and often have only 2-3 small paragraphs of information on the actual case;

In hundreds of cases, the hunters are given verbal warnings and no fines.

The Georgian administrative code allows returning the gun to hunters even when the judge rules an administrative crime has been committed. Court papers don’t always indicate what happened to the gun, but in at least 58 out of 390 cases the gun was returned.

In 2014, 337 administrative and one criminal case were filed by the country’s Agency of Protected Areas; in 2015, 404 administrative and 6 criminal cases; in January-September 2016, 310 administrative and 7 criminal cases.

According to the Agency’s administration, in the last 10 years, two rangers were killed on the job. In late February, a ranger was found dead near Kaspi in central Georgia. Investigators are indicating that this death was not related to the poaching of animals.

Near Obuji village in northwest Georgia, Tarash Meskhia caught three wolf cubs in the forest and took them home. He put their photos online and offered to sell them for 1,000 GEL (about $377). One cub died before local environment inspectors detected the crime.

The court papers do not specify the fate of the two surviving cubs. Meskhia was fined 300 lari (about $US 113).

Walking into a protected wildlife area with a gun brings a fine of only 250-300 lari (about $US 96-113) and the gun is returned. A case is considered poaching only when a dead animal is found. Considering rangers have to patrol on average 1,841 acres per day, poachers are tough to catch.

Rangers do not have search and seizure authority of suspects in protected areas. They can only write what they see in field reports, which are used in court cases.

Typically when a ranger sees suspicious hunter, he calls either the police or an environment inspection agent -- both have the authority to file a criminal case with the local court. But the ranger can’t detain suspects and by the time other authorities arrive, evidence can be destroyed.

Cases with insufficient evidence may not reach the court, and even if they do, the court many times decides not to even accept it.

Tsira Gvasalia, ifact.ge