Free or Fearful? The Fear of Floating in the South Caucasus

The ISET Economist, a blog about economics in Georgia and the South Caucasus by the International School of Economics at TSU (ISET)

By Davit Keshelava & Yaroslava Babych

In economics there is a long-standing debate on whether emerging markets should adopt a fixed exchange rate currency regime or leave their exchange rates up to markets to decide. Intuitively, exchange rate is just another price, similar to the price on a sack of potatoes, a liter of milk or a kilogram of honey. Except that exchange rate is the price of 1 unit of foreign currency (say, 1 US dollar) in terms of our domestic currency. Textbook economics would tell us that price flexibility is essential for markets to function well, to quickly clear up any shortages or surpluses that may arise on the markets. So, if it is bad for the government to regulate prices on potatoes, milk or honey, is it a good idea to regulate the exchange rate?

Indeed, for many years researchers keep asking this question and providing sophisticated and detailed answers. If we follow famous exchange rate models describing the most optimal currency regimes for an emerging market economy, we would probably make a good case for having a flexible exchange rate.

WHY IS A FLEXIBLE EXCHANGE RATE GOOD FOR the ECONOMY?

|

Source: Daily Reckoning |

In a small open country, subject to frequent and large external shocks, the exchange rate plays a role of shock absorber and smooths the effect of negative disturbance on the country’s economy. For example, a negative output shock will most likely cause domestic currency to depreciate against the foreign currency. This depreciation can be a blessing in disguise for domestic exporters, who will become more competitive on the foreign markets, and so on…

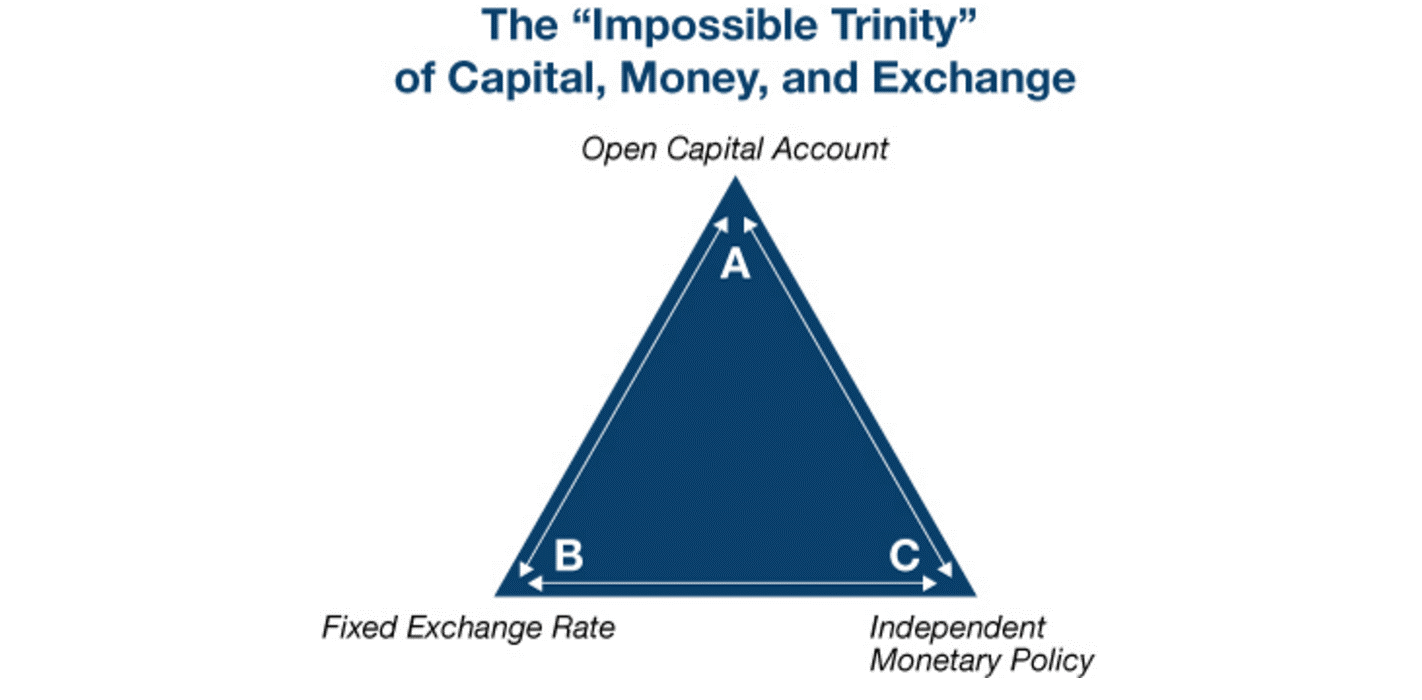

Furthermore, unlike fixed exchange rates, a free-floating regime guarantees an independent domestic monetary policy. Economists call this phenomenon “impossible trinity” - a concept which states that it is impossible to have a fixed exchange rate, free capital movement and an independent monetary policy at the same time. Therefore, facing increasingly integrated capital markets, policymakers are forced to make a choice between free monetary policy and exchange rate stability.

To understand the idea behind “impossible trinity,” imagine a hypothetical country that fixes the exchange rate against the US dollar and allows free movement of capital. Let’s say that in order to reduce inflation, the central bank of this country decides to contract the money supply by increasing domestic interest rate, while the interest rate set by US Federal Reserve remains the same. The increased interest rate differential will make the domestic currency of the country more attractive for foreign currency investors, who are constantly looking for higher returns. Thus, the demand for local currency will increase and the exchange rate will be pushed to appreciate. Ultimately the peg with the US dollar will break.

In addition, a flexible exchange rate regime does not require the country’s central bank to accumulate large amounts of foreign exchange reserves to defend the currency peg against a potential speculative attack. Furthermore, to have a hard peg or any type of fixed exchange rate, countries need sufficient foreign currency inflows over time, while for many underdeveloped small open economies this is still a problematic issue.

In summary, there is overwhelming evidence that maintaining a stable and predictable exchange rate is very costly.

THE FEAR OF FLOATING PHENOMENON

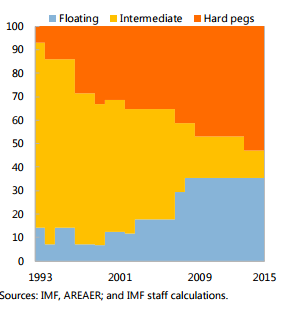

While an increasing number of emerging countries are officially classified as free-floaters, a closer look at the empirical evidence reveals that it is common for these countries to have very tight monetary policies and frequent interventions in the currency market aimed at preventing sharp depreciation of the domestic currency.

Calvo and Reinhart (2000) first described this phenomenon and dubbed it “fear of floating”. The fear manifests itself through mild exchange rate fluctuations, but also high interest rate and reserve volatilities in emerging market countries. According to the authors, as many as 76.4% of the emerging economies classified as free-floaters are affected.

Calvo and Reinhart (2000) constructed the Calvo-Reinhart Fear of Floating Index (C-R Index) that puts exchange rate volatility in relation to the variability of the policy instruments (nominal interest rate and official reserves). A low value index would indicate a country with a high “fear of floating”. Despite the fact that the C-R Index is very far from being a perfect indicator of the “fear of floating,” it still provides some information about the attitude of a central bank toward the volatility of the exchange rate.

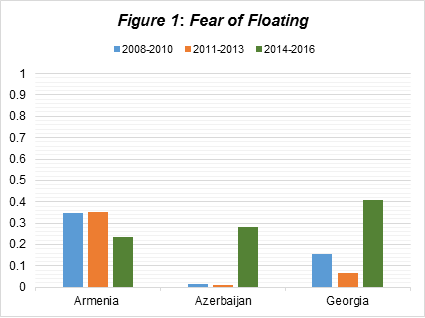

When we apply the Calvo and Reinhart (2000) method and compute the C-R index for Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan we can see some interesting patterns.

We discover that the C-R index was close to zero for all these countries even at the time of the devaluation wave during the latest regional crisis.

It is not surprising that Azerbaijan has the lowest index values in the two corresponding periods in 2008-2010 and 2011-2013. Before the end of 2015, the country was operating with a fixed exchange rate that theoretically guarantees a C-R index very close to zero.

|

Source: International Financial Statistics of the International Monetary Fund

|

However, even after moving to a floating exchange rate regime in 2015, Azerbaijan’s “fear of floating” index was not much different from that of Armenia and Georgia.

It is also notable that during the recent regional crisis, Georgia was the least “fearful” country, letting its currency float more than its neighbors did.

If we separately observe the components of the “fear of floating” index, we discover that the exchange rate is the least volatile variable in a majority of cases, while policy rates have the highest volatility, especially for the Georgian economy.

WHY DO COUNTRIES FEAR FLOATING?

There is broad literature that tries to identify what is behind the decision to intervene and smooth exchange rate fluctuations. First, as Belhocine et al. (2016) claims, the degree of exchange rate volatility is closely related to a country’s experience of high inflation or hyperinflation during transition – the higher the peak inflation in the early 1990s, the more likely a country was to maintain a fixed exchange rate or to allow de facto floating. All three countries in the South Caucasus region experienced hyperinflation in the early transition years.

Second, according to Castro (2004), when the country’s central bank cares a lot about inflation and exchange rates are very likely to quickly affect prices (the pass-through effect from exchange rates to prices is strong), then it is logical for the central bank to try and smooth currency fluctuations.

The pass-through effect is especially strong for net importer countries such as Georgia and Armenia. In Georgia’s case, 1% change in the nominal exchange rate causes approximately 0.42 percentage point change in the long-run price level and the pass-through time is 4-5 months (Tamar Mdivnishvili, 2014). The main idea behind the pass-through consideration is that large exchange rate volatility leads to higher price volatility which reduces the credibility of policymakers committed to inflation targeting.

Third, most transition countries are characterized by high asset and liability dollarization. For instance, in Georgia, the Loan Dollarization Ratio exceeds 60% for recent several years (65.4% in 2016), while the Deposit Dollarization Ratio is even higher in the last two years (71.4% in 2016). If domestic residents borrow in foreign currency, while their income is denominated in domestic currency (this phenomenon is called currency mismatch), a depreciation of national currency makes it harder for borrowers to get their loans back (now borrowers have to spend a larger share of their income to repay their loans) which leads to a contraction of aggregate demand and output. This phenomenon is widely recognized as a contractionary depreciation.

Finally, it is a well-known fact that most developing countries are unable to borrow in their national currency. Economists even have a special name for this phenomenon – “original sin”. In this scenario, devaluation of the domestic currency significantly increases the debt burden for these countries and further stimulates policymakers to keep the exchange rate as stable as possible.

In summary, although the central banks of emerging small open economies realize the benefits of a free-floating exchange rate regime, there are several things that prevent them: Past experiences of high inflation, a pass-through effect from exchange rates to prices, contractionary depreciation (high currency mismatch) and the “original sin” problems do not let them overcome a strong fear of floating, and the countries continue to bear the high costs of smoothing exchange rate fluctuations.