Can Quotas Do It?!

The ISET Economist, a blog about economics in Georgia and the South Caucasus by the International School of Economics at TSU (ISET)

Despite substantial improvements in education, professional development and political participation, women remain underrepresented in leadership positions in politics, and Georgia is no exception. In 2017, the country ranked in 94th place (out of 144), according to the Global Gender Gap index (GGI)1, which indicates that Georgia is not performing well in closing the gender gap. The GGI serves as a comprehensive and consistent measure for gender equality, which can track a country’s progress over time. Economic participation and opportunity, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment are the four main determinants by which the GGI measures gender parity. It does not come as a surprise that out of these four categories, the most problematic for our country is the political one. For political empowerment, Georgia is ranked as 114th, with a score of just 0.0932. However, Georgia is not alone here - the worldwide gap between women and men on economic participation and political empowerment is wide (only 58% of the economic participation gap has been closed). And here comes a question - what measures should be taken to solve this problem and reach gender balance in political institutions in our country and worldwide?

The Working Group on Women's Political Participation (Task Force) believes that introducing a legislative gender quota system in Georgia is the answer. In many countries, policy-makers have introduced gender quotas in politics, and this is perceived as one of the most popular remedies for overcoming the problem - in fact, half of the countries of the world today use some type of electoral quota for their parliaments.

A gender quota refers to requirements for the number of women in political positions. Changing the gendered nature of the public sphere, and inspiring women to get more politically involved, underlines the core motives for introducing this policy.

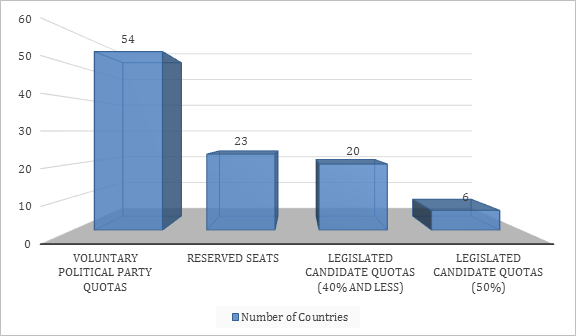

Most scholars recognize three basic types of quotas: reserved seats, party quotas, and legislative quotas. A reserved seats quota system guarantees women representation in the parliament. It is used as a more direct way of regulating the number of women in elected positions. This system reserves positions for which only female candidates can compete. Notably, out of the three types of quota systems, reserved seats are the least popular (see Figure 1).

At their most basic, party quotas are measures adopted by individual parties on a voluntary basis. Political parties set targets to include a certain percentage of women as election candidates. Given that voluntary party quotas are not mandated by law, they are not legally binding, and so there is no sanction system. The only way governments can intervene in party quota cases is to incentivize the parties to increase the number of women in their electoral lists in different ways (financial incentive systems are the most widespread). This is the case in Georgia also - since 2011, parties that include two women for each 10 candidates receive 10% more core funding from the government. In 2014, incentive funding was increased further.

Legislative quotas tend to be found mostly in developing countries, especially Latin America, and post-conflict societies, primarily in Africa, the Middle East, and Southeastern Europe. This is the newest type of quota policy, first appearing only in the 1990s. Legislative quotas are mandatory provisions that apply to all parties. This quota system refers to the electoral process - parties are obliged to include a certain number of women in their candidate lists, mostly in the 25% to 50% range. Moreover, parties can only replace a candidate with a candidate of the same gender; however, if no such candidate exists, the mandate is canceled.

Moving on to Georgia, with the goal of making Georgian women more active and empowered, the Task Force initiated the introduction of a gender quota system in 2017. This draft law proposed a 50% quota for the next parliamentary election: that is, every other person on the list should have been of a different sex. The legislative initiative was presented to the Parliament but was rejected in March, 2018. However, supporters in Parliament and civil society promised to initiate a new version of the law, the details of which remain unknown.

You may hear success stories about how gender quotas changed political empowerment patterns and reduced gender gaps. According to GGI, Iceland has closed more than 70% of its gender gap, followed by Nicaragua, Rwanda, Norway and Finland. These stories are intriguing, however, political environments, institutional development and political will are still country-specific factors that can stop each type of gender quota system from being “a silver bullet.”

As summarized by the World Development Report 2012, “Gender Equality and Development,” gender quotas, in theory, have the potential to correct market failures in the existing system. This instrument could potentially improve the aspirations of women and help them overcome self-imposed stereotypes, and may also reduce statistical discrimination due to lack of information on female abilities, thereby changing attitudes and social norms towards women in the long-term. On the other hand, such measures could also reduce efficiency, if less able and qualified women are to be selected and promoted through application of this tool. Quotas could also have an adverse impact on incentives for females to invest in their education and self-development. Last, but not least, quotas can further undermine the image of women as qualified candidates, since they help generate beliefs that female candidates succeed only because of the artificial policy measures put in place. This belief could actually become self-fulfilling, if it disincentivizes qualified women from entering a political race.

While it has been demonstrated that in many countries quotas have led to a significant increase in female representation, especially so in closed list proportional representation systems, empirical evidence analyzing the impact of such policies remains limited. Possible correlations between policy outcomes and quota-induced increases may not reflect the causal impact of quotas and reverse causation may also be the case. In other words, is it female representation that changed outcomes for women, or is an improved environment for female politicians strengthening gender representation in parliaments? Moreover, other factors, such as boosting overall female empowerment in a country, can determine both policy outcomes and quota-induced increases, but this cannot be interpreted as a causal relationship.

Evidence from a couple of countries that have provided researchers with a more robust venue for causal impact analysis of gender quotas is mixed at best. Randomized allocation of gender quotas at the local government level in India has been shown to reduce the corruption practices of local bureaucrats; however, against expectations from female leaders for more pro-female policies, the same studies cannot confirm impact of gender on the policy outcomes. Albeit in a different context, the introduction of gender quotas at the corporate board level in Norway has adversely influenced short-run profits of the companies affected by the policy.

While nobody questions the necessity of empowering women in Georgia, broader tensions also need to be considered if quotas are to be used to increase women’s political representation. Limiting voters’ rights to vote for the candidate he/she thinks is best inherently undermines democratic principles. So this distortion has to be balanced against expected benefits; however, as mentioned above, debates about merits of such interventions remain unresolved in the academic literature.

Introduction of a strictly enforced 50% legislated quota will most likely increase women’s representation in the government. However, by artificially correcting outcomes, it is highly unlikely that we will be treating underlying causes. Unless we have better understanding as to what really deters Georgian women from entering and succeeding in a political race, the risks and costs remain unwarranted. An option one could take is to replicate the Indian “experiment” and introduce quotas on a rolling basis at the local government level. This “natural experiment,” as researchers like to call it, could help bring about more certainty and free policy debate from ideological bias.

By Lika Goderdzishvili