Is Kobiashvili the Man to Repair Georgian Football after its Summer of Discontent?

A new low in the FIFA world rankings, first round exits of every Georgian club involved in European competition and an administrative blunder which saw Georgia’s captain wrongly left out of a Euro 2016 qualifier have been the lowlights of a summer to forget so far for football in a country that once contributed significantly to the top level of the beautiful game.

As a capacity crowd drifted away from the Tengiz Burjanadze Stadium in Gori on July 21 having watched Dila Gori, Georgian champions and the country’s last remaining representatives in European competition, succumb meekly to a scarcely impressive Partizan Belgrade side, verdicts of doom and gloom reverberated in the cars and bars.

For some years now, Georgians have been losing affection for domestic football. When asked about the state of football in the country, most Georgians will deliver a swift and damning description of its recent failures, and perhaps move the conversation swiftly on to rugby, a sport where Georgia are quickly emerging as a respected world force.

You will still encounter Georgians of a certain vintage who will regale you with tales of the legendary Dinamo Tbilisi sides of the 1960s and the late 1970s and early 1980s which conquered the Soviet Union and became a feared opponent in Europe, lifting the European Cup Winners’ Cup in 1981 at the zenith of their excellence.

The Soviet Union side that won the first ever European Championships in 1960 contained three Georgians, one of whom – Slava Metreveli – scored a decisive goal in the final against Yugoslavia.

Two Georgians also featured in the 1972 European Championships final while the 1982 Soviet Union World Cup team, which advanced to the second round, was littered with Georgians.

Following independence, Georgia initially had an ensemble of talents to be envied with Giorgi Kinkladze, Giorgi Demetradze, Temur Ketsbaia and Shota Arveladze providing an attacking threat that pushed a country undergoing civil turmoil to within touching distance of Euro 96, edged out in qualifying by Stoichkov’s Bulgaria.

Nearly 20 years later, Georgia languishes outside the world’s top 150 in the FIFA world rankings and its poorly attended and financially impoverished league is beginning to slide further into the wilderness in UEFA’s coefficient system.

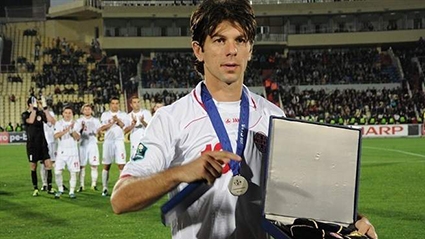

Naturally, with such a dispiriting state of affairs, questions are being asked of the competence of the national governing body, the Georgian Football Federation (GFF). One of its most outspoken critics is Levan Kobiashvili, the recently retired midfielder who earned 100 caps for his country and spent the bulk of his career in Germany’s Bundesliga.

Kobiashvili has expressed his intention to run for the GFF presidency at the next elections, and launched a scathing attack on the current administration after it wrongly informed Georgia head coach Kakha Tskhadadze that captain Jaba Kankava would be unavailable for their Euro 2016 qualifier with Poland in June due to suspension. In actual fact, Kankava, having received two yellow cards in the campaign instead of the necessary three, was free to play.

“The executives of the Georgian Football Federation once more demonstrated their irresponsibility and lack of professionalism, when due to their carelessness an important national team player could not participate in a qualification game,” stated Kobiashvili on his official Facebook page.

Whether Kankava’s inclusion would have spared Georgia from the defeat they suffered in Poland is debatable but Kobiashvili’s anger was understandable. He then took the criticism a step further, essentially demanding a changing of power in Georgian football.

“The damage the governing body of the GFF has done to Georgian football leaves them with no moral right to stay responsible for it in future. I think the time has come for the current leadership to go. They have to apologize to the supporters, set the date of the elections and stop doing a job they lack competence and expertise in!” concluded Georgia’s most ever capped player.

Kobiashvili appears to be positioning himself for a tilt at the presidency, and has been gaining greater prominence in the public eye, most recently attending an opening ceremony for the Olympic village for the imminent European Youth Olympic Festival in Tbilisi.

The German media have also lent their support to Kobiashvili with Berliner Zeitung’s Robert Matiebel claimed in the wake of the FIFA scandal that broke out in late May that “Kobiashvili and his love of sport outweighs any greed. These types of people are needed in sports organizations and if so, the risk of corruption would be much less.”

In its defense, the GFF, currently presided over by Zviad Sichinava, can point to improving performances at youth level. Georgia reached the finals of the European under-17 championships in 2012 and the European under-19 championships in 2013, and Georgian sides at both levels have consistently reached the elite round of youth competitions in the last few years.

The GFF has also secured the right to host the 2017 European under-19 championships, as well as the UEFA Super Cup taking place in less than three weeks in Tbilisi.

Georgia also has far greater priorities than football right now. The currency devaluation, omnipresent tension over the occupied territories and recovering from the catastrophic June 13 floods are just some of the pressing issues which render football utterly trivial by comparison.

However, there is little question that Georgia is massively underachieving in a sport that once brought pride to its people. It has to be a source of envy if not embarrassment for the GFF that, with a fraction of the budget, the country’s rugby authorities have made incredible forward strides in the last decade while football has been in a spiral of regression for as long as some Georgian fans have been alive.

Whether Kobiashvili is the white knight ready to revive Georgian football remains to be seen, but from the murky depths in which the national sport currently wallows, he appears to be worth the gamble.

Alastair Watt